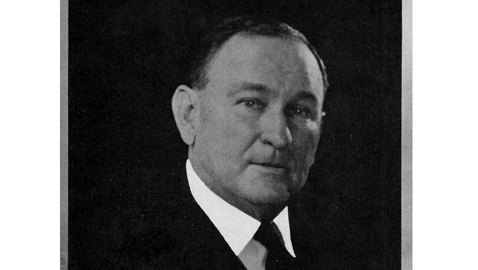

From the author’s personal collection.

Formal portrait of Senate Majority Leader Joe T. Robinson, circa 1932.

Joseph Taylor Robinson was Majority Leader of the United States Senate during the first one hundred days of Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal. Few politicians have enjoyed the breadth and length of the career Joe T. Robinson had in Arkansas. A forceful leader, dynamic and plainspoken, Joe Robinson was a man of burning ambition. Yet his ambition would hasten his death.

Born August 26, 1872 in Lonoke County, Arkansas, Joe Robin’s father, James Madison Robinson, was a physician, farmer and sometime preacher of the gospel. Robinson’s mother, Matilda Swaim Robinson, was a native of Tennessee. Robinson’s formal education was spotty; he attended a one-room schoolhouse, largely during the summer months, yet he also possessed an inquisitive mind and read extensively from his father’s large personal library. Young Joe also knew the meaning of hard physical labor, chopping cotton on his father’s farm, as well as tending to the apple orchard. Joe Robinson quickly developed into something of a prodigy, displaying a remarkable talent for public speaking at an early age. Robinson won several oratorical contests, excelling at both political and religious oriented speeches. At only seventeen, Joe Robinson took the required exam and received a license to teach school. After having taught for two years, he entered the University of Arkansas, intending to eventually get a law degree. Robinson’s education was interrupted by the untimely death of his father in 1892. Rather than attend the university, Robinson “read” the law under the tutorship of Judge Thomas C. Trimble.

Joe Robinson was only twenty-two years old when he ran for and won a seat in the Arkansas House of Representatives. Robinson also found time to court and marry Ewilda Grady Miller in 1896. “Billie” Miller was one of the great beauties of her day and their marriage lasted until Robinson’s death, although they never had children.

Robinson did not seek reelection to the Arkansas House of Representatives, preferring to concentrate upon his law practice. Joe Robinson became quite a successful lawyer and his firm counted many of the biggest businesses in Arkansas amongst its clients. Yet Robinson was not done with politics and in 1902 he ran for Congress and won.

Joe Robinson’s tenure in the U. S. House of Representatives was not an especially happy time for the young congressman, as for most of his time, the Democrats were in the minority. Robinson chaffed under the Republican rule and by 1912 he was eyeing the Senate seat held by Jeff Davis.

Senator Davis was one of the most controversial and polarizing political figures in Arkansas, yet he was also one of the most popular. Joe Robinson quickly concluded he could not beat Davis, who was one of the most able demagogues of his time. Robinson instead turned his sights on the governorship. He challenged incumbent George Washington Donaghey, who had promised not to seek a third two-year term in office. Governor Donaghey changed his mind, a decision that proved to be politically disastrous. Congressman Robinson beat Donaghey badly, winning 66% of the vote in the Democratic primary.

Robinson won the general election and had not even taken the oath of office when Senator Jeff Davis died suddenly of a heart attack. The legislature elected Joe Robinson to the United States Senate in a closely contested vote. Still, Governor Robinson managed to push several important pieces of reform legislation before resigning on March 8, 1913 to take his seat in the U. S. Senate.

Senator Robinson took office as Woodrow Wilson assumed the presidency. Since the election of Abraham Lincoln, the only Democrat to occupy the White House had been Grover Cleveland, who had won two nonconsecutive terms. Wilson had been elected due to a split in the Republican Party between former president Theodore Roosevelt and incumbent William Howard Taft. Robinson strongly supported Wilson and his administration and worked very hard at being a senator. Robinson was recognized as one of the best parliamentarians in the Senate and his reputation for ability and understanding the rules helped him to become Democratic leader in 1923.

In 1924, Joe Robinson was the “favorite son” candidate of his state at the ill-fated Democratic National Convention, which required 103 ballots before selecting a presidential nominee.

Many thought Senator Robinson a decent presidential prospect in 1928, especially after he took to the floor of the United States Senate to denounce religious prejudice. Senator J. Thomas Heflin of Alabama, a virulent racist, was anticipating the nomination of Alfred E. Smith, the Catholic governor of New York, Heflin incited considerable religious prejudice against Catholics and Joe Robinson gave the Alabama senator a tongue lashing, as well as the Ku Klux Klan. Smith did win the Democratic presidential nomination that year and chose Joe Robinson as his running mate. Governor Smith calculated having a Southerner on the ticket might mitigate his being a Yankee, as well as any handicap his religion might inflict upon his candidacy.

Although Senator Robinson campaigned all across the country, his being the vice presidential nominee did little to help Al Smith. Smith was solidly against prohibition and his Catholicism was not well received in the South. Smith lost badly to Republican Herbert Hoover, who carried Virginia, Texas, Tennessee, North Carolina and Florida. The Democrats barely managed to carry solidly Democratic Alabama, as Senator Heflin bolted the party to oppose Smith.

Still, even Herbert Hoover recognized Joe Robinson’s ability and appointed the Arkansas senator to the American delegation attending the Naval Disarmament Conference in London. Robinson returned to his post in the Senate and pressed for and won passage of the treaty resulting from the London conference.

Shortly after Hoover came to office, the stock market crashed and the Great Depression began. Senator Robinson was an effective leader for Senate Democrats and he kept them well organized in opposing many of President Hoover’s policies. Robinson was intent upon doing all he could to alleviate the suffering of the people of Arkansas and the country. When Hoover lost to Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1932, the Democrats gained control of the United States Senate and Joe T. Robinson became Majority Leader.

Despite having the majority in the Senate, more than a few Democrats were somewhat wary of FDR’s proposals. Joe Robinson worked hard to pass President Roosevelt’s legislative agenda. His forceful personality and leadership style kept Democrats from defecting.

Darrell St. Claire was a long-time employee of the United States Senate (as well as the son-in-law of Tennessee Congressman Sam D. McReynolds) and in an oral history for the Senate Historian’s Office, recalled Senator Joe T. Robinson.

“He was one of the greatest men I think I ever saw,” St. Claire said. “He was a tremendous, commanding person, with a terrifying open air voice. He could visibly shake the chamber when he wanted to. He never used a note, never used a paper.”

Darrell St. Claire remembered that Robinson “…sat afternoon after afternoon on the floor, waiting, cajoling, counseling, not saying a great deal, but just by his very presence commanding people to keep still and get on with it.”

Joe Robinson was so faithful in promoting and passing Franklin Roosevelt’s legislation that he ran afoul of Senator Huey P. Long of Louisiana. All too often today Huey Long is remembered as some sort of backwoods buffoon, but Darrell St. Claire in his oral history points out the true nature of the Louisiana “Kingfish”. Asked by the interviewer if Long was “just a clown”, St. Clair quickly demurred.

“No, no. He was probably one of the most extraordinary minds that was ever on the floor,” St. Claire replied.

St. Clair opined that had Long “stayed in the profession of law he would have been probably one of the finest trial lawyers, possibly even one of the finest trial judges that ever lived in the United States.”

Long was a brilliant, shrewd and calculating politician and his power was growing. Even FDR was concerned by Long’s growing national prominence. Roosevelt considered Huey Long one of the two “most dangerous men” in the United States; the other being General Douglas MacArthur.

The list of Democratic politicians who considered themselves responsible for Franklin Roosevelt’s nomination in 1932 was likely miles long, but Huey Long had more reason than most to take the credit. Long kept the wavering Mississippi delegation from leaving FDR for another candidate at a particularly critical moment, helping to avoid a stampede for another contender. Yet, Long quickly soured on Roosevelt.

The Louisiana Kingfish once famously compared Republican Herbert Hoover and Democrat Franklin Roosevelt.

“Hoover is a hoot owl,” Long explained, “and Roosevelt is a scrootch owl. A hoot owl bangs into the nest and knocks the hen clean off and catches her while she is falling. But the scrootch owl slips into the roost and scrootches up to the hen and talks softly to her. And the hen just falls in love with him, and the next thing you know there ain’t no hen.”

The exchanges between the Majority Leader and Senator Long became more and more heated. Robinson had difficulty in holding his temper and when thoroughly irritated or genuinely angry, his face became empurpled with rage. Long rather enjoyed baiting Robinson and never seemed to lose his own temper. Yet the Louisiana Kingfish demonstrated his considerable political appeal in a way that became a genuine threat to Joe Robinson.

When Arkansas’ junior United States senator, Thaddeus Caraway, died following an operation in 1931, the governor appointed his widow, who won a special election to serve through in 1932. Hattie Wyatt Caraway was a quiet homebody who was somewhat out of place in the United States Senate. Almost always dressed in black, she never spoke on the floor, preferring to read newspapers and do crossword puzzles at her desk inside the Senate chamber. Mrs. Caraway had been appointed precisely because the governor wished to avoid choosing from a host of candidates hungering to go to the Senate, as well as the fact the new senator promised not to run, a pledge Senator Caraway insisted she never made. The widow persisted, paid her filing fee and wrote in her diary she realized she had no chance of winning the election. Senator Caraway sat near Huey Long on the Senate floor and the Kingfish watched his new colleague and noted she was one of the few members who voted for his bill to restrict wealth. Curious, Long continued to watch Hattie Caraway’s voting record and was surprised she always voted against what the Kingfish considered to be the predatory special interests. Few politicians or members of the press took Hattie Caraway seriously. One reporter described Mrs. Caraway as “a demur little woman who looks as though she ought to be sitting on a porch in a rocking chair, mending somebody’s socks.”

Huey Long decided to go to Arkansas and campaign for Hattie Caraway.

Arriving with a contingent of aides, several sound trucks, and literally tons of printed campaign literature carried by seven large trucks, and the Kingfish’s personal limousine, Huey Long entered Arkansas and made a whirlwind campaign lasting just nine days. Speaking multiple times daily, Long mesmerized audiences in largely rural settings. Senator Caraway faced six men in the Democratic primary, one of whom had the personal support of Majority Leader Joe T. Robinson.

Mrs. Caraway had a shy, almost retiring nature and her first attempts at public speaking did not much impress anyone. Yet Senator Caraway made a simple and effective appeal.

“I know I don’t talk like a statesman, but I’ve always tried to vote like one for you,” she told audiences.

Huey Long’s own appeal was instantaneous and astonishing.

“Think of it my friend!” the Kingfish cried. “In 1930 there were 540 men in Wall Street who made $100,000,000 more than all the wheat farmers and all the cotton farmers and all the cane farmers in this country put together. Millions and millions and millions of farmers in this country, and yet 540 men in Wall Street made $100,000,000 more than all those millions of farmers. And you people wonder why your belly is flat up against your backbone!”

Huey Long’s populist message, his ability to move his audiences was unquestioned and the election results stunned just about everybody. Senator Caraway won a clear majority of the vote and was the first woman ever elected to the United States Senate.

Nobody was more surprised than Joe Robinson and Huey Long continued to taunt the Majority Leader, saying he intended to come to Arkansas and campaign against him in 1936. Fortunately for Joe Robinson, Huey Long was dead by the time the Majority Leader came up for reelection, felled by an assassin’s bullet. Robinson was easily reelected and President Roosevelt personally visited Little Rock and Robinson’s home, where a sumptuous luncheon was served.

Joe Robinson’s last battle was waged on behalf of FDR, as well as to satisfy his own ambition. Roosevelt unveiled his proposal to enlarge the U. S. Supreme Court, catching Congress and his own advisors by surprise. There was an immediate insurrection inside the Senate and the Republicans wisely adopted a clever strategy of allowing the Democrats to fight amongst themselves. Montana progressive Burton K. Wheeler led the fight against FDR’s court packing plan and Robinson remained on the defensive much of the time. If anything, Robinson fought all the harder because President Roosevelt promised to gratify the Majority Leader’s crowning ambition. Joe Robinson was to get one of the first appointments to the newly enlarged Supreme Court.

Yet it was not to be. The easily angered Majority Leader overworked himself and it became readily apparent he was tiring himself beyond all reason. Robinson was not feeling well and left the Senate early and returned to his apartment in the Methodist Building. A maid found the senator the next morning, clad in his pajamas, surrounded by copies of the Congressional Record, the victim of a heart attack on July 14, 1937.

Joe Robinson was taken home to Arkansas and buried in Little Rock.

Robinson remains to this day one of the more able Majority Leaders in the history of the United States Senate.