By Ray Hill

Political parties are not successful simply because of the candidates running to represent those parties, but rather because of issues and those people working hard in the background. The infrastructure of a political party is very important to overall success. In reflecting back, it is all too easy to overlook the differences between then and now. History cannot be accurately viewed through the prism of today, but only through the spectrum of the times.

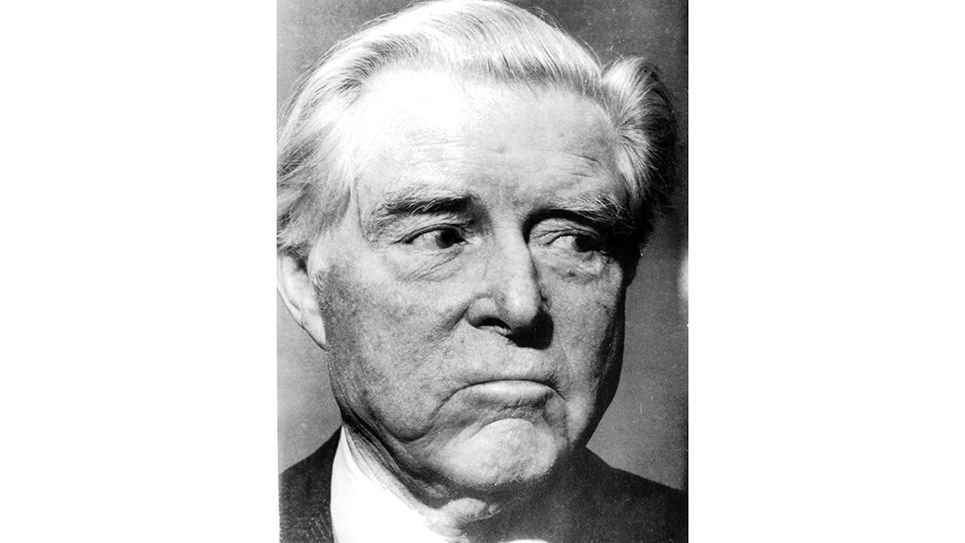

Emma Guffey Miller was a pioneer for the rights of women. Mrs. Miller was a Democrat in a state that was, throughout much of her life, solidly Republican. Emma Guffey Miller is one of the longest-serving members of the Democratic National Committee, serving from 1932 until her death in 1970, a remarkable thirty-eight years. “I was born to politics,” Mrs. Miller often said. The year before her death, she told one visitor, “I’ve gone to every Democratic convention since 1924.” Indeed, Emma Guffey Miller was also the first woman nominated for president at that same convention. One reporter recalled Emma Guffey Miller “took pleasure in shocking people with her frankness and her youthful manners.” Reporter Frank M. Matthew remembered Emma Guffey Miller as “sharp-minded, sharp-tongued, demanding, witty, full of remembrances that ranged across two centuries. . .”

Mrs. Miller could trace back her own participation in Democratic politics to the 1880 election when she was six years old. The Guffey family was then living in Greensburg, Pennsylvania and there had been a torchlight parade held for General Winfield Scott Hancock, the Democratic nominee for president. “My father was chief marshal,” Mrs. Miller remembered. “He rode in front on a beautiful bay horse with a red sash and a silk hat, and our house was on the main street.

“I was waving like mad, and one of the marchers brought me a Roman candle – – – I’d never seen one before – – – and my brother said ‘Hold it high.’ But I didn’t and it shot balls of fire right across the street into the front of a Republican house.” Emma Guffey Miller paused. “I’ve been shooting at Republicans ever since.”

Professionally, Emma Guffey Miller was a school teacher, although her real vocation was politics. Throughout her life, Mrs. Miller would wield considerable influence in both Washington, D.C. and Harrisburg, the capitol of Pennsylvania.

Mrs. Miller made no pretense of being bipartisan; indeed, by the time of her death, she was described as “Mrs. Democrat.” Emma Guffey Miller was a highly partisan Democrat. Frank Matthews recalled Mrs. Miller as having been “triumphant with her party’s winners and compassionate with its losers and forever unforgiving of the Republican party, its men and its works.”

At the 1968 Democratic National Convention, Mrs. Miller recalled when delegates largely traveled by train rather than flying. “We used to go by special train. It would start in Philadelphia and pick up delegates and spectators all along the way,” Mrs. Miller said. “I remember once there was a woman from one of the eastern counties who fainted or had a heart seizure, or something, and somebody asked if anybody had any whisky.

“Well, sir, a flask came out of every berth. I never laughed so much in my life. That’s what prohibition did.” Needless to say, Mrs. Miller was a highly vocal and active opponent of prohibition.

Mrs. Miller was and remains the oldest person to serve on the Democratic National Committee, dying when she was ninety-five years old. Emma Guffey Miller laughingly referred to herself as the “old gray mare” of the Democratic Party. That particular nickname came when Senator Joe T. Robinson of Arkansas, then the vice presidential running mate of Al Smith in 1928, had toasted Mrs. Miller, saying, “Here’s to the Old Gray Mare – – – Emma Guffey Miller. She’s better than she used to be.”

While she liked to say she was averse to candidates backed by political machines, in truth her brother Joseph F. Guffey was the Democratic “boss” of Pennsylvania while he occupied a seat in the United States Senate from 1935-1947. Joe Guffey was one of the most ardent supporters of President Franklin Roosevelt to sit in the United States Senate. One contemporary assessment of Senator Joe Guffey was written by Isaiah Berlin, who provided confidential reports about the Senate Foreign Relations Committee to Britain’s Foreign Office. Berlin wrote Senator Guffey was “a noisy supporter who wraps himself in the Roosevelt flag and has been advocating for a fourth term for some time.” Berlin described Guffey as a “very typical Pennsylvania politician who has decided to throw his lot in with the President and has thus become an obedient party hack not of the purest integrity.”

Emma Guffey Miller’s prominence inside the Democratic Party was through her own persistence, hard work and accomplishments rather than any reflected glory from her brother. One editorial at the time of her death noted there were a large number of people who liked Mrs. Miller, yet who could not stand Senator Guffey “for a variety of reasons.” Mrs. Miller seconded the nominations of Alfred E. Smith and Franklin D. Roosevelt for the Democratic nomination for president in 1928 and 1932, respectively. Once the Democrats came back to power, her husband Carroll was appointed to serve on the Interstate Commerce Commission by President Roosevelt. Carroll Miller was chairman of the ICC in 1937.

One could easily discern the relationship between Emma Guffey Miller and her brother, as there was a distinct family resemblance. Emma Guffey Miller was plainspoken and fought for what she believed in, especially for the rights of women. One of eight children, Emma Guffey Miller’s political career practically began at birth. The Guffeys were a political family and her father was elected sheriff of Westmoreland County. Indeed, Emma Guffey was born at Guffey’s Station along the Youghiogheny River. The Guffey family later moved to Pittsburgh when Emma was a teenager.

“We’ve been around western Pennsylvania a long time,” Mrs. Miller once explained. “Patrick Campbell was in the Black Watch at Fort Duquesne. But you never know what will turn up when you trace your ancestry.

“We found one whom Charles II had executed and (had) his head posted on London Bridge because he was the lawyer who prosecuted Charles I for treason.”

Like many people who have participated in politics for a long time, Emma Guffey Miller had a wealth of stories she liked to share. Mrs. Miller enjoyed recalling elections in Westmoreland County after the votes had been counted and those counting the ballots had put aside partisan differences to have a drink of “Old Possum Hollow.”

“That’s how we knew the count was finished,” Mrs. Miller laughed. “Old Possum Hollow was the most famous rye whisky ever made, long before Overholt. My father always said it was because of the water they had.”

At a time when most women did not attend college, Emma Guffey was a member of the Class of 1899, graduating from Bryn Mawr. Mrs. Miller graduated with a degree in history and, of course, politics. Emma Guffey Miller taught briefly in the Pittsburgh area and in Japan, where she lived for a time. She later married and had four sons. Mrs. Miller was able to indulge her interest in politics due to the fact she, along with her brother Joe and sister had invested in oil, which provided them with a comfortable annual income.

Described as “an engaging, but tough minded woman,” politicians dismissed Emma Guffey Miller as simply another nice old lady and soon discovered their mistake. One officeholder who was defending his stance of opposing women driving automobiles, pointed out it would not be safe for them to drive at night. “Hire more policemen,” Emma Guffey Miller snapped.

During a meeting of the Democratic National Committee in 1967, in anticipation of the 1968 convention, a rule was proposed that no candidate for delegate to the national convention would be discriminated against because of “race, religion or national origin.” Emma Guffey Miller immediately insisted the word “sex” be added to the statement.

For years, Emma Guffey Miller had been the head of the National Women’s Party, which sought an amendment to the Constitution stating the “equality of rights under the law shall not be denied by the United States or any state on account of sex.”

Emma Guffey Miller lived at Wolf Creek Farm near Slippery Rock, Pennsylvania, maintaining a home there from 1920 until her death. She also shuttled back and forth between Pennsylvania and Washington, D. C. where she lived in the spacious home occupied by her bachelor brother, Joe.

Mrs. Miller backed Senate Majority Leader Lyndon Johnson over Senator John F. Kennedy in 1960. As she passed ninety, Emma Guffey Miller remained active and alert; in fact, the only concessions she made to aging were her acknowledgments that she was hard of hearing and needed a cane. Mrs. Miller was the guest of honor at the 28th anniversary of the Democratic Women’s group in Lancaster County. Her estimation of Lyndon Johnson remained consistent, saying, “I’m 100 per cent behind him.” When Johnson was challenged by Eugene McCarthy for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1968, Emma Guffey Miller said of the Minnesota senator, “A fine man but he’s not getting anywhere.”

Although she had ardently supported the Catholic Al Smith in 1928, some were puzzled when she voted for Lyndon Johnson rather than John F. Kennedy. Mrs. Miller explained she didn’t believe a Catholic could win the general election. When reminded of her support for Al Smith, Emma Guffey Miller coolly replied, “Well, young man, Al Smith was different because he was against prohibition.” Mrs. Miller’s personal contempt of prohibition knew no bounds and she simply ignored it until she helped to place a plank in the 1932 Democratic platform promising to repeal it. Commenting upon her ferocious opposition to prohibition, Mrs. Miller said it caused everyone in Slippery Rock to think “I was a drunk.”

Mrs. Miller was credited with helping a woman win the Democratic nomination for the United States Senate seat her brother had once occupied. Genevieve Blatt, the State Secretary of Internal Affairs, won the nomination over Judge Michael Musmanno in 1964 in what was described as a “cliffhanger” of an election.

When she died, the press in Pennsylvania took note. One editorial began by reminding its readers of the old adage, “Never underestimate the power of a woman.” The editorial stated while that same adage “may not have been intended to fit Emma Guffey Miller” yet “it fit her precisely.” The Pittsburgh Press wrote “Emma Guffey Miller lived a life of immense usefulness, constant activity and sparkling experience. Her drive helped push many a good cause toward completion.” The editorial concluded by stating, “Mrs. Miller will be long remembered by the many people who worked with or against her. Or just knew her for the good fighter she was.”

Contemporary newspaper reports gave conflicting causes of death for Emma Guffey Miller; she had been admitted to a local hospital following either a heart attack or stroke. Mrs. Miller slipped away a few hours later. Frank M. Matthews, a writer for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette scoffed at the notion Emma Guffey Miller had suffered a heart attack. “Every politician in the country knows that this grand old woman of the Democratic party would not go that way,” Matthews wrote. “She wouldn’t suffer a heart attack; she’d fight it until she ran out of breath.”

“Just like she didn’t suffer arthritis,” Matthews added. “It made her walk all bowed over and with a cane, but Mrs. Miller herself declared that she didn’t suffer, and the cane was always handy to rap for attention.” Frank Matthews thought since Emma Guffey Miller had been around longer than anyone else, it simply seemed she was a fact of life.

By any measure, living a life of “immense usefulness” is a fitting and fine epitaph for any reasonable human being.