Published March 26, 2012

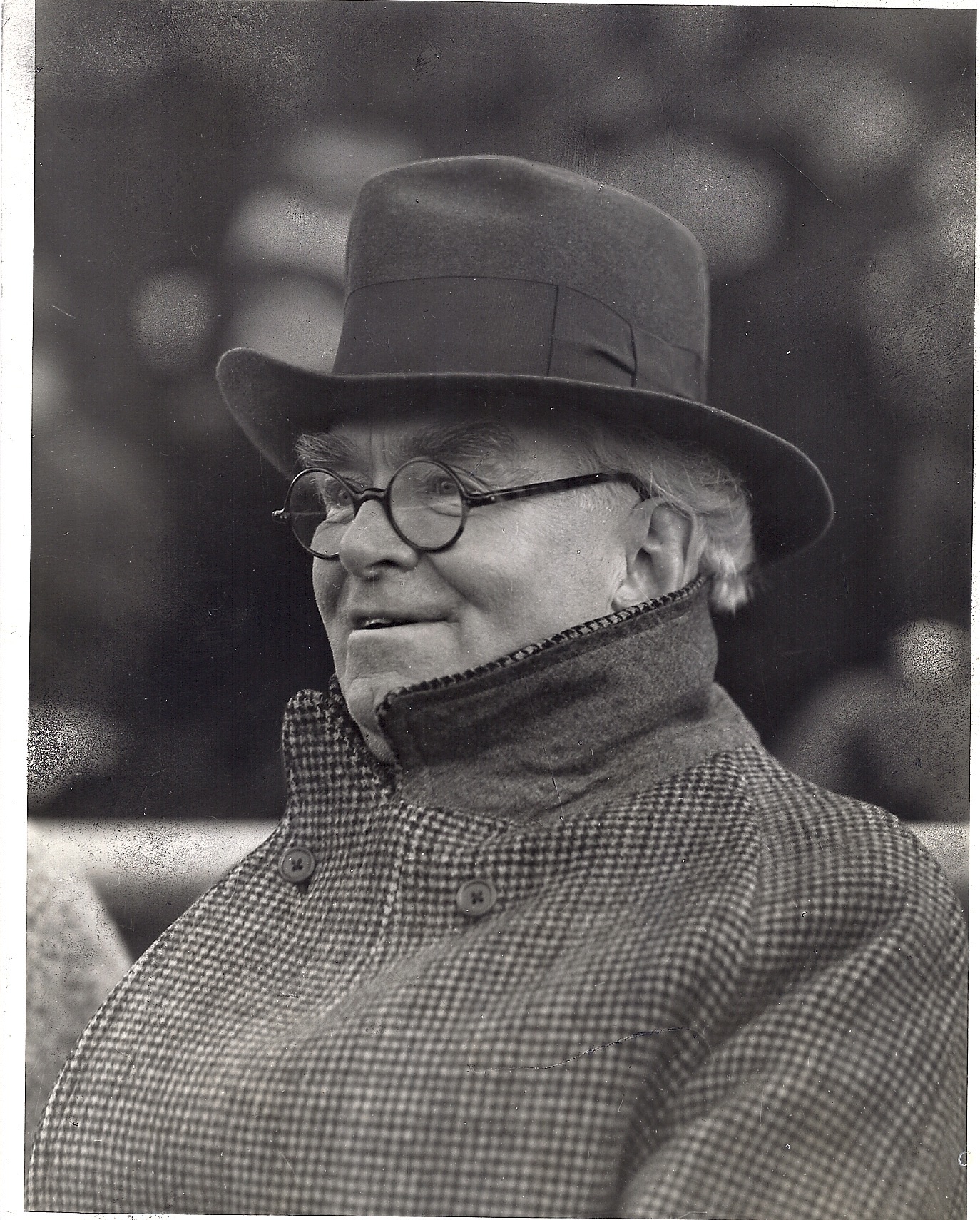

The modern history of Memphis is inextricably tied to that of Edward Hull Crump. “Mister” Crump was indisputably a political boss in a region of the country where political bosses did not normally flourish. Political bosses were hardly uncommon in the United States during the heyday of E. H. Crump and they still exist today, albeit in lesser forms. The product of political machines in the United States have at least a few who have risen to the presidency of the United States. Chester Alan Arthur was a political boss from New York State and occupied perhaps the biggest plum within the gift of the president at the time, as the Collector of the Port of New York. Arthur later infuriated many of his own supporters by supporting civil service and saw his backing melt to the point where he could not muster enough delegates to be nominated for the presidency.

President Harry S. Truman was also a product of the infamous Pendergast machine in Kansas City, Missouri. Tammany Hall in New York City is perhaps the most notorious example of a political machine and Boss Tweed the noxious example of a political boss. The HBO cable network has even launched a very successful series based on the life and dealings of New Jersey political boss, Enoch “Nucky” Johnson.

Chicago has a long history of political machines and the last vestige of the old Daley machine, Richard Daley, Jr., just retired as Mayor of Chicago. Frank Hague, the boss of Jersey City, was infamous for shouting, “I AM THE LAW!” during one outburst and in New Jersey, he was.

These same political machines have elected everything from aldermen and city councilmen, to county clerks and Presidents of the United States. Machines have helped to determine the outcome of national elections, just Chicago Mayor and Boss Richard Daley, Sr., held back the vote returns from Cook County to push Illinois into John F. Kennedy’s column in one of the closest presidential races in our country’s history and giving JFK the presidency with the gift of Illinois’ electoral votes. Lyndon Johnson was elected to the United States Senate through ballot boxes controlled by George Parr, the “Duke of Duval” County.

There have been many men described as political bosses, but if the definition were “one who runs a fully functioning political organization,” the number would drop appreciably. By any standard, Edward Hull Crump would qualify as a political boss as he presided over one of the most smoothly functioning organizations in the country. Through his mastery of the Shelby County political machine, Crump ruled absolutely in Memphis for nearly half a century.

E. H. Crump became a force to reckoned with, not only locally, but in Tennessee and national politics as well. Crump, in conjunction with Tennessee’s U. S. Senator Kenneth D. McKellar, dominated Volunteer State politics for the better part of two decades.

Born in Holly Springs, Mississippi, Crump came to Memphis as a fresh-faced young man with a full head of flaming red hair, causing later political opponents to refer to him as the “Red Snapper.” Like many of his contemporaries, Ed Crump grew up relatively poor as his father died young from yellow fever. Employed as a bookkeeper as a teenager, Crump fell in love with and married the daughter of a prosperous merchant, who provided Crump with the funds to purchase the firm where he worked.

It is ironic to consider E. H. Crump first entered politics as a reformer. Many Memphians were chafing under the rule of Mayor John J. Williams, who had annexed communities adjacent to Memphis, which had the happy effect of increasing the government’s revenues and expanding services. Williams was evidently a live-and-let-live sort of fellow, as the Mayor did not work very hard in actually enforcing local vice laws. Some accused the Mayor of being too closely aligned with saloon owners and the liquor interests, which was a damning charge during a time when Tennessee was frequently embroiled in a debate on the question of prohibition. That same debate was so fierce it left one former United States senator literally lying dead in a gutter.

In 1905 many of the leading citizens of Memphis revolted and sought to drive Mayor John Williams from office by reforming local government and creating a commission form of government. Crump was elected as a member of the City Council as part of the progressive movement. Crump was closely associated in the reform movement with a young attorney, K. D. McKellar, and the two would remain friends, confidants and political partners for the next five decades.

Crump soon proved to be a master at organizing and was a particularly effective administrator. The breadth and scope of the Crump organization is difficult to conceive in today’s political atmosphere. While many would hardly be shocked to consider a genuine political machine composed of public employees, the Crump organization extended into virtually every aspect of the political, business and social fabric of Memphis and Shelby County. Even many progressives became stalwart members of the Crump machine, along with socially prominent citizens, business and labor leaders, and educators. The Crump organization permeated civic associations, clubs, neighborhood groups and even churches. All fifty-two voting precincts had Crump leaders and each was tightly organized.

Crump improved government efficiency while at the same time getting more out of the various governmental departments in terms of services to the citizenry. While a poor public speaker, the future Memphis Boss possessed an unrivaled sense of political showmanship, as well as a remarkable ability to shrewdly size up his fellow human beings. Crump’s organizational skills, ability to understand people and events, as well as his showmanship were all crucial factors in his being able to parlay those strengths into a winning campaign to unseat Mayor John J. Williams.

Crump’s inability to make a speech didn’t much hurt him in the campaign, as he relied upon the organization he had so carefully crafted. Others carried the burden of making speeches, while Crump himself concentrated on turning out the vote. It proved to be a highly effective method of winning elections and would remain so until the end of Crump’s life. Never in his long reign did the Memphis Boss ever take an election for granted.

E. H. Crump was not one to ignore a life lesson and he did not soon forget his political ambitions had quite nearly been upset by former Mayor Williams’s overwhelming support from the black community. Unlike many Southern cities, African-Americans owned businesses and were not only allowed to vote in Memphis, but actually encouraged to vote. The various competing political organizations in Shelby County and Memphis paid the poll taxes for African-American voters with the clear expectation they would vote “right” and they usually did. Crump immediately set out to switch the political allegiance of African-American citizens to his own organization, although Memphis was still very much a segregated city at the time.

Mayor Crump saw to it that city services were provided to African-Americans, something that was virtually unheard of in most of the South. Crump’s close ties to the black community would be a source of contention in the future with many of his political opponents outraged by the notion African-American citizens were voting and participating in Democratic primaries. It was hardly unusual for Crump opponents to appeal for support on the basis of nominations being determined by the vote of African-Americans. Many of those same appeals were not surprisingly blatantly and crudely racist. Crump’s relationship with the black community would change over the years and the Memphis Boss tolerated no dissent, a lesson some would learn to their ultimate regret in the future.

E. H. Crump survived a bid by former Mayor John Williams to recapture his old seat of power and Crump was busy consolidating his power in Memphis and Shelby County when his tenure abruptly came to an end. It was a humiliation he never forgot nor forgave. As former Mayor Williams had turned a blind eye to much of the rampant crime and vice in Memphis, Crump started a very public campaign to clean up the city. The effort did not last and Crump likely realized it was not possible for local government to stamp out of existence prostitution, gambling, and saloons. Rather than attempting to eliminate vice completely, Crump moved to confine prostitution to a red-light district, tolerated saloons and kept the gambling dens manageable. The vice interests were largely ignored for the most part, but those same interests were expected to contribute to the well being of the Shelby County political machine. One Chief of the Memphis Police Department testified the contributions from illegal operations amounted to almost one hundred thousand dollars, a sum that would be the equivalent to several million dollars today. Some have described those funds as “protection money,” but likely the bulk of it was used to fund political activities and campaigns for the Shelby County machine and its candidates. Crump saw nothing wrong with assessing the illegal businesses operating in his domain to perpetuate his machine any more than he objected to legitimate businesses contributing to the organization. Crump did, however, strongly object to the notion of any official taking the money to fill his own pockets.

It was Crump’s refusal to enforce the prohibition laws in Memphis that lead to his removal from the Mayor’s office. Tennessee’s then-Governor Ben W. Hooper was not only a prohibitionist, but a Republican. Governor Hooper supported an ouster law which enabled the removal of Crump as Mayor of Memphis by the judiciary. E. H. Crump, ever practical, resigned as Mayor just before he could be ousted from office.

Crump’s removal as Mayor, while widely hailed by his opponents, did little to tarnish his reputation in Memphis and Shelby County. It did nothing to diminish his actual power. Crump was elected as Shelby County Trustee mere months after leaving the mayor’s office. It might seem an odd choice for Crump to serve in an obscure county office, but state law at the time allowed the Trustee to personally keep excess fees, usually amounting to approximately $50,000 per year, an enormous sum in 1916. In today’s dollars, adjusted for inflation, it was almost a million dollars.

As E. H. Crump assumed the Trustee’s office, he was soon able to extract a measure of revenge on former Governor Ben W. Hooper.