By Ray Hill

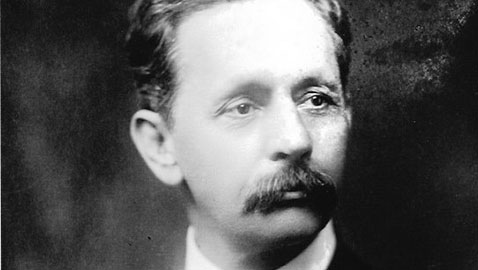

John Knight Shields, Tennessee’s senior United States senator, had first been elected in 1913. Shields had served for a decade on the Tennessee Supreme Court before becoming the last man to be elected to the U. S. Senate by the state legislature. Shields had been reelected in 1918, defeating Tom C. Rye, who had been governor of Tennessee during World War I. Shields was a slight man with a sensitive face dominated by a bristly moustache. Senator Shields might have been slight, but he possessed a big streak of cantankerousness. Rye ran as an all-out supporter of President Woodrow Wilson. Wilson was highly popular in Tennessee and Shields had also pledged his support to the President. After the election, Senator Shields made tens of thousands of Tennesseans livid when he refused to support American entry into the League of Nations through the Treaty of Versailles. Shields had incensed many Tennesseans by supporting reservations to the treaty sponsored by Senator Henry Cabot Lodge of Massachusetts, a Republican.

Tennessee’s junior senator, Kenneth D. McKellar, was an ardent supporter of the League. McKellar deeply admired Woodrow Wilson, perhaps as much as John Knight Shields disliked the President.

Shields was not a good speaker during an age when many of the most successful politicians in the country excelled at stump speaking. It was McKellar who likely saved John Knight Shields from defeat in 1918. Shields had telephoned Senator McKellar to say he had heard rumblings President Wilson intended to write a letter for publication denouncing him; a letter written by the President stating Shields was no friend to him or his administration almost certainly would have ended the Tennessean’s political career. When Senator McKellar visited the White House and asked Wilson about the letter, the President readily confirmed he was going to write a letter stating John Knight Shields was unfriendly to him. McKellar begged, cajoled, and pleaded with the President not to write the letter. McKellar never got a direct commitment from Wilson, but the President did not write the letter.

McKellar believed Shields would support the President and was utterly astonished after the election when John Knight Shields barked the President and presidential secretary Joe Tumulty could go straight to hell.

A combine of “Independent” Democrats and Republicans had first elected John Knight Shields to the U. S. Senate in 1913; the “fusionists” in Tennessee had already elected Tennessee’s other U. S. senator, as well as the governor. Plainspoken, Senator Shields was a frequently difficult man who oftentimes could not get along with his own appointees.

As stubborn and curmudgeonly as he was, there was little doubt John Knight Shields would seek a third term in 1924, yet few believed he would not draw a serious challenger for the Democratic nomination. In fact, he drew two formidable challengers inside the Democratic primary: General Lawrence D. Tyson and Nathan L. Bachman. All three candidates were from East Tennessee. Shields lived on a gentleman’s farm, “Clinchdale,” near Bean Station. General Tyson was from Knoxville and his stately home still sits on the site of the University of Tennessee. Nathan L. Bachman was from Chattanooga, living in a grand home on Signal Mountain.

Lawrence D. Tyson was a very successful businessman and quite wealthy, but he was universally known as “General” Tyson. As the only Tennessean to have achieved the rank of general during World War I, L. D. Tyson won the immediate respect of thousands of Tennesseans and was venerated by many veterans. Having graduated from West Point, few could dispute Tyson’s military credentials and the future general had actively participated in the wars against the Apaches in the West and their leader, Geronimo, as a young Lieutenant. The original source of Tyson’s wealth was his wife, Bettie McGhee, the daughter of Charles McClung McGhee. McGhee was the president of a railroad, as well as prominently involved in several other business enterprises. It was Tyson’s father-in-law who helped secure for him an appointment in 1901 as professor of military science and tactics at the University of Tennessee. McGhee’s reasoning was quite simple; by having Tyson teach at UT, it brought his daughter and grandchildren closer to home. L. D. Tyson used his time teaching at the University of Tennessee to better himself, earning a law degree. Tyson left the faculty of the university in 1895 to practice law. Tyson served as a colonel during the Spanish-American War and returned home to Tennessee as a brigadier-general. When the United States entered the First World War, Lawrence D. Tyson eagerly sought to renew his military commission. President Woodrow Wilson complied, giving the fifty year-old Tyson the opportunity to serve. Tyson commanded the “Old Hickory Division” and he and his troops were the first to enter Belgium during the summer of 1918. Tyson’s division fought bravely, helping to capture, along with British troops, much of the Hindenberg Line in the area. Nine men in Tyson’s Fifty-Ninth Brigade were awarded the Medal of Honor, while the general himself was the recipient of the Distinguished Service Medal.

After the war, L. D. Tyson came home to Knoxville to supervise his many business interests, which included owning textile mills and coal companies. Tyson sat on the Board of Directors of two Knoxville banks and anticipating his bid for the United States Senate, bought the Knoxville Sentinel. The General still had his military bearing and his white hair and neatly trimmed moustache gave him the air of a statesman.

Nathan Lynn Bachman was evidently a man almost impossible to dislike. An amiable man who had practiced law in Chattanooga since 1903, Bachman had been a Circuit Court judge for six years before winning election to the Tennessee Supreme Court. Bachman had resigned his position as an associate justice of the state Supreme Court to run for the United States Senate. Nathan Bachman apparently had a bottomless well of amusing stories and was a noted raconteur. Judge Bachman was one of those rare men who made friends by the score wherever he went.

At the time, it was unusual for campaigns to last much longer than a couple of months. In 1924, the aspirants for the United States Senate in Tennessee were moving around the state well before the first of the year. There was ample reason for Senator John Knight Shields to be concerned. Many Tennesseans had not forgotten his refusal to support President Wilson. Democrats in Carroll County met in convention and heartily endorsed the administration of Governor Austin Peay; at the same time, they voted to condemn the record of Senator John Knight Shields. Democrats in Carroll County sought to endorse the candidacy of L. D. Tyson, which not surprisingly met with resistance from the supporters of Judge Bachman. A compromise was reached, omitting an endorsement of any senatorial candidate, but the resolution condemning Senator Shields’ record was adopted.

It was clear the issue of Woodrow Wilson and the League of Nations would follow Senator John Knight Shields throughout the 1924 campaign. Wilson had died February 3 that year and the memory of the stricken and ill former president burned brightly in the hearts of many Tennesseans. Wilson had bitterly excoriated several Democratic U. S. senators who had fought his administration. Senator James K. Vardaman of Mississippi, the infamous “White Chief”, had gone down to defeat inside his own primary in 1918, largely because of a letter written by the former president, which became public. Before he died, Woodrow Wilson penned the letter which he had failed to write in 1918. The late president told one correspondent in Tennessee that John Knight Shields had been the “least trustworthy” of his many associates in public life. It was certainly true John Knight Shields had frequently voted with the Republicans in the Senate for the reservations to the League of Nations. Felled by a serious stroke, Wilson had been obsessed on the topic of the League and had been inflexible in refusing to accept any reservation to the treaty. Nor was Wilson capable of accepting even the mildest of disagreement with his foreign policy from fellow Democrats. Senator Oscar W. Underwood of Alabama had long been friendly to Wilson, yet when Underwood voted for a “separate peace” with Germany, the President considered it the height of treachery. Underwood compounded his sin by serving on a delegation with the patrician senator from Massachusetts, Henry Cabot Lodge, the author of most of the reservations to the Treaty of Versailles. Wilson snapped, “If Underwood is a Democrat, then I am a Republican.”

John H. Clarke, a former justice of the U. S. Supreme Court and the president of the League of Nations, spoke in Asheville, North Carolina and called for the defeat of Senator John Knight Shields. It was potent evidence that supporters of the League and President Wilson had not forgotten John K. Shields. Clarke worried that with two strong candidates opposing the senator, Shields might squeeze through the Democratic primary and win reelection to the Senate. “One of the two candidates opposing him should retire and make the defeat of the present Senator possible,” Clarke thundered. The former justice said if neither Tyson nor Bachman could agree as to which of them should drop out of the race, they should draw lots. Quite likely Senator Shields believed having two opponents for the Democratic nomination made it much easier for him to win the primary election. Both Tyson and Bachman had already opened their statewide headquarters before March of 1924; Senator Shields announced the opening of his own headquarters in the Hermitage Hotel the first week of March.

John H. Clarke was hardly the only Democrat who worried John K. Shields might win a plurality of the vote and the Democratic nomination. Luke Lea, publisher and owner of the Nashville Tennessean, had served with John Knight Shields in the United States Senate for four years. To say the two did not get along would be gross understatement. Shields had backed then-Congressman Kenneth D. McKellar inside the Democratic primary against Senator Lea. Lea had run third in a primary contest with McKellar and former governor Malcolm Patterson. Lea had not forgotten the opposition of his junior colleague and his newspaper was solidly against the reelection of John Knight Shields. The Tennessean complained, “If people by their indifference allow Senator John K. Shields to be elected to the Senate, happily a minority candidate, they’ll deserve the shame they bore for the last six years, and no bonus and no anything to boot.”

General Tyson raised the issue of a debate between the candidates for the senatorial nomination; more specifically, the debate should focus on the issue of whether Senator Shields had been “untrue” to the Democrats of Tennessee. “If Senator Shields and Judge Bachman desire a debate,” Tyson said in a statement released by his headquarters, “I shall be very glad to make it a three-cornered affair and shall ask that I be included and given a division of the time.” It was the General’s opinion that Senator Shields had already been judged by Tennessee Democrats to have been faithless. “I do not feel it incumbent upon me or necessary to show wherein Senator Shields has failed to abide by the principles advocated by his party. His record is well-known in this state, and the Democrats have already judged on this point.” General Tyson noted while Shields was likely “busy” performing his duties in Washington and probably would not accept an invitation for a joint debate, the old soldier scoffed at the notion Shields defied anyone to point to any instance where the senator “had been untrue to the principles of the Democratic party…”

The 1924 campaign for the United States Senate had begun early in Tennessee and it promised to be a hot fight between three well-qualified candidates. It would be a long, hot summer in Tennessee.