By Ray Hill

From 1930 until 1964, the Democratic Party reigned supreme in Tennessee. Republicans had only occasionally been able to elect a governor; the last was Alfred A. Taylor in 1920. That year had been something of a high watermark for the GOP. Republicans had won the governorship, as well as five of Tennessee’s ten congressional districts. Even Cordell Hull was swept out of his seat in the heavily Democratic Fourth Congressional district in 1920. Two years later, Tennessee Democrats were united and won back the governorship and three of the five seats in Congress held by the GOP.

Republicans were more fortunate in winning votes in presidential years. Warren Harding had won Tennessee in 1920 and Herbert Hoover carried it in 1928, at least in part because of the Catholicism of Democratic nominee Alfred E. Smith. Even Davidson County, a rock-solidly Democratic area, supported Hoover. General Dwight D. Eisenhower carried the Volunteer State in 1952 and 1956, albeit narrowly. Richard Nixon fared much better in 1960, winning Tennessee by better than 75,000 votes against John F. Kennedy (also a Catholic).

Republicans were elated in 1962 when William E. Brock had won election to Congress from Tennessee’s Third Congressional district, which included Chattanooga. The incumbent congressman from the Third District had been James B. Frazier Jr., scion of one of Tennessee’s oldest political families. Named for his father, who had been both a governor and United States senator from Tennessee, Jim Frazier had first been elected to Congress in 1948 when Estes Kefauver had vacated his seat in the House to run for the Senate. Frazier, past seventy, was a figure from a different era. Courtly and more conservative than many inside his own party, Frazier seemed not to fit in with the administration of the young President Kennedy and his court in the new “Camelot.” Frazier was upset in the Democratic primary by Wilkes Thrasher Jr. All the candidates running in the Third District had been from political families. Thrasher’s father had been the county judge in Hamilton County, while Bill Brock’s grandfather, the original William Emerson Brock, had been appointed to fill a vacancy in the United States Senate in 1929 and served until 1931. The elder Brock had also been the founder and owner of the Brock candy company and had invented the chocolate covered cherry.

No longer a Democrat, Bill Brock had become active in the Young Republicans and had worked hard for Richard Nixon in 1960. Brock would likely have lost had Congressman Frazier been renominated in 1962. The congressman’s loss caused just enough of his more conservative supporters to vote for Brock instead of Wilkes Thrasher Jr. Democrats hoped Brock’s election to Congress was a fluke and looked forward to beating him in 1964.

The death of Estes Kefauver on August 10, 1963, necessitated an appointment by Governor Frank Clement. Clement, after a four-year hiatus from the governorship, had reclaimed the governor’s mansion in 1962, although not without a fight. Against a weak field of opponents, the well-financed Clement had won almost 100,000 more votes than his nearest competitor. Yet there was a warning sign in the primary; Clement won with only 42% of the overall vote. There was a portent of future problems for both Frank Clement and the Democratic Party in the 1962 general election results. Clement won a bare majority of 50.85% of the vote in the November election. An Independent, William Anderson, won an astonishing 32.83% of the vote while Hubert Patty, the GOP nominee, took just over 16% of the vote. Democrats saw little to be concerned about at the time; Anderson, the one-time commander of the submarine Nautilus, was a Democrat. Many Tennessee Democrats felt the Volunteer State was still safely a bastion for the Democratic Party. After all, Hubert Patty could not even poll 20% of the vote in the general election.

Lyndon Johnson was running hard in 1964 for a term in his own right after the tragedy of the Kennedy assassination. Yet initial polls in Tennessee shocked Democrats with Arizona U. S. Senator Barry Goldwater leading by more than 20 points. Senator Albert Gore, the “Old Gray Fox” of Tennessee politics was running for a third term in the U. S. Senate, while Congressman Ross Bass of Pulaski was gearing up to run for the seat once held by Estes Kefauver.

Frank Clement had considered running against Albert Gore in 1958, but thought better of it and practiced law for four years before making his comeback bid for governor in 1962. Clement could not run for governor again in 1966 as Tennessee, at the time, did not allow governors to serve two consecutive four-year terms. Rumors abounded in Nashville that Clement wanted the Kefauver seat for himself. The responsibility for appointing a successor to Estes Kefauver fell to Governor Clement and he made a logical choice when he appointed Herbert S. Walters of Morristown. A millionaire businessman, Walters was past seventy and had rendered yeoman service to the state and national Democratic parties. A supporter of Lyndon Johnson for the 1960 Democratic presidential nomination, Walters went to Washington where he supported much of LBJ’s “Great Society” legislation. Neither of Tennessee’s U. S. senators supported Lyndon Johnson’s Civil Rights Act of 1964. Nor did any of Tennessee’s congressmen, save for Richard Fulton of Nashville and Ross Bass.

Although both men denied it vociferously, it seems quite likely “Hub” Walters never seriously considered waging a campaign to succeed himself in 1964. After Senator Walters indicated he would not be a candidate, Governor Clement made the announcement just about everybody in Tennessee expected: Frank Clement would run for the United States Senate in 1964. M.M. Bullard, a wealthy businessman from Cocke County in heavily Republican East Tennessee, rounded out the three-candidate field for the nomination for the “short term” Senate seat. The winner of the 1964 election would have to run again for a full six-year term in 1966.

Senator Kefauver had a legion of personal friends, acquaintances, followers and the semblance of an active organization in Tennessee, much like the actively functioning machine that had been built by Senator Kenneth D. McKellar earlier. Much of Kefauver’s following coalesced behind the candidacy of Congressman Ross Bass after the late senator’s widow Nancy refused to consider a campaign. Bass was thought to be more liberal than Governor Clement and there was a sharp edge to the dislike of Frank Clement by many Kefauver’s admirers inside Tennessee’s Democratic Party.

Governor Clement had access to considerable campaign funds and state employees who were only too glad to campaign for their chief. Still, there were troubling rumors from the State Capitol about the youthful governor’s addiction to alcohol. Only forty-four years old in 1964, Clement had first been elected governor in 1952 at age thirty-two and was a hardened veteran of Tennessee’s political wars.

Ross Bass attracted much of the old Kefauver organization, as well as support from organized labor and African-Americans. Most observers were stunned by the results of the primary which Bass won by almost 100,000 votes. Frank Clement had won just under 36% of the vote. It was Clement’s first political defeat and it hurt, badly.

Much to the surprise of some Democrats, Tennessee Republicans had nominated credible candidates for both of Tennessee’s Senate seats. Howard Baker Jr. was the son of the late congressman from Tennessee’s Second Congressional district. The elder Baker had died unexpectedly in January of 1964 and his son and namesake had rejected the idea of going to Congress to replace his father. Howard Baker Jr. preferred to try and win a seat in the U.S. Senate and at that time, Tennessee had never popularly elected a Republican to sit in the Senate.

Albert Gore was being challenged by Dan Kuykendall, a young businessman from Memphis, where the vestiges of the old Crump machine were slowly making their way to the Republican Party. Congressman Clifford Davis, first elected to Congress in 1940, had been defeated in the Democratic primary in 1964 by George Grider. Davis had been hand-picked by the Memphis Boss to run for Congress in 1940 and was the last of the old machine politicians in what was left of the Crump-dominated Shelby County.

Middle-class voters, as well as the country club set, were finding themselves uncomfortable with many of the nominees of the Democratic Party in Tennessee and, at least at the beginning of the campaign, Barry Goldwater was generating some real excitement amongst a large swath of Volunteer State voters.

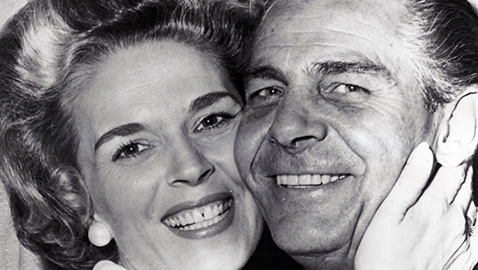

Democrats were astonished to observe people flocking to events in cities, hamlets and counties which had once been citadels of the Democratic Party. Howard Baker Jr. was married to Joy Dirksen, daughter of one of the most remarkable politicians of that or any other age. Everett Dirksen had first been elected to Congress in 1932, a terrible year for most Republicans as Herbert Hoover was being flushed out of office by Franklin D. Roosevelt and a Democratic sweep. Dirksen remained in Congress until 1948 when he voluntarily retired due to difficulties with his vision. His eyesight restored, Dirksen challenged Scott Lucas, Majority Leader of the U. S. Senate, in 1950 and won convincingly. Everett Dirksen remained in the Senate for the rest of his life. By 1964, Dirksen wore horn-rimmed glasses that framed his face, which was well worn with wrinkles. His head was crowned by a nest of tousled curls and his voice was an instrument made for political speech-making. Indeed, Dirksen’s sibilant voice was the source of a hit album and record “Gallant Men.” Called the “Wizard of Ooze” by detractors, Everett Dirksen was a wily politician and nationally recognized. At the time, Dirksen was the Senate’s Minority Leader.

A veteran of thousands of chicken dinners on the campaign circuit, likely nobody in America had campaigned for more GOP candidates than Everett Dirksen. It surprised nobody when Everett Dirksen came to Tennessee to campaign for his son-in-law, Howard Baker.

The Chattanooga News-Free Press offered Baker an endorsement in his race against Ross Bass. The News-Free Press firmly believed the record of Congressman Ross Bass was “leftist” and that he deserved to be rejected by the people of Tennessee, but the newspaper also thought Howard Baker was well equipped to represent the people of Tennessee in the United States Senate. The News-Free Press believed Baker to be “morally, philosophically, mentally and patriotically” fit to be “an outstanding senator” for the Volunteer State.

Barry Goldwater’s lead in Tennessee began to melt. Many Republicans were surprised, puzzled and aghast when the Arizona senator campaigned in Knoxville and said not a single word about Howard Baker who had introduced him. Nor did Goldwater offer to mention Dan Kuykendall or congressional candidate Bob James when campaigning in Memphis.

The local ticket mates were more cooperative. Congressman Jimmy Quillen, then seeking his second term, was with Howard Baker in Hawkins County when they cut the ribbon to open the Republican headquarters there in October. Quillen asked the people of the heavily Republican First District to give Baker and Kuykendall the “biggest vote in the history of the Republican First.” The Greater Chamber of Commerce of Knoxville received an unhappy jolt when its planned “meet the candidate” event was spurned by Senator Albert Gore and Congressman Ross Bass. Invited to “discuss the issues,” neither Senator Gore nor Congressman Bass apparently liked the idea of joint conversations with their opponents.

The Knoxville Journal printed a story pointing out Congressman Ross Bass’s wife, Avanell, worked as a member of her husband’s staff. The Journal said Mrs. Bass had earned $95,427.01 since 1956, winning annual raises until her salary had reached $13,409 in 1963.

Franklin D. Roosevelt had been enormously popular in Tennessee and FDR had carried the Volunteer State four times. Harry Truman, over the opposition of Ed Crump of Memphis (the Memphis Boss had supported Strom Thurmond and the “Dixiecrats”), had won Tennessee. In 1964, Tennessee was a battleground state for both the Republicans and the Democrats.