Bluegrass Statesman

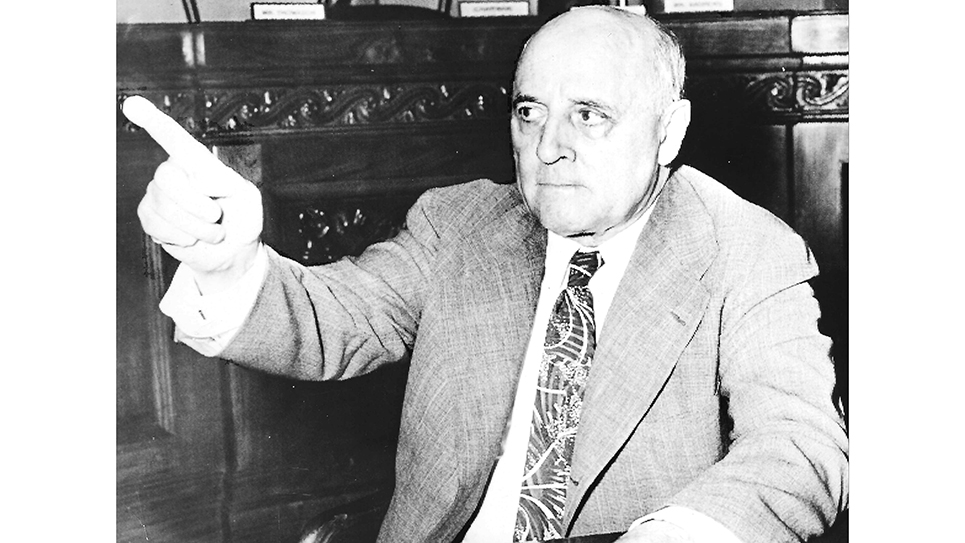

Marvel M. Logan of Kentucky

By Ray Hill

“The old have wisdom that the young know not of,” Marvel Mills Logan once wrote. With each passing day, the more I agree with that statement.

Marvel M. Logan is a name long forgotten by most, but for a time he was one of Kentucky’s most important officials. Logan had made his career as an attorney, rising to sit on Kentucky’s State Court of Appeals. That proved to be a springboard for his election to the United States Senate. Lawyering was the typical profession in both the Senate and the House. In 1934, 68 of 96 senators were lawyers by profession; 251 congressmen were attorneys out of 435 members. At that time, many of the lawyers in Congress still practiced law to help make ends meet. As the Senate considered tightening the rules (it was already illegal for attorneys who were also members of Congress to represent clients before any department of government), Senator Marvel M. Logan said, “I do not think any member of the U.S. Senate should be allowed to practice law … So far as money and property are concerned, I suspect I am the poorest man in the Senate … But I would find some other way of making a living without accepting fees from those who have business with the Congress of the U.S. or I would go home and resign … “

Some on Capitol Hill referred fondly to Senator Logan as “Colonel” because he exemplified the state he represented in the United States Senate. Some newsmen referred to the Kentuckian as the “Sage of Capitol Hill.” As a member of the U.S. Senate, Logan always had a keen interest in events and enjoyed sharing his opinion on virtually any topic with newsmen. The Kentucky senator was a favorite of reporters for his ready wit, open-door policy and informal attitude. Logan also was courteous, as was always expected of a near-Southern senator. Senator Logan insisted upon keeping his office open at all hours, which likely frustrated his weary staff and was one of the few members of the United States Senate who kept “office hours” even while Congress was in recess.

Something of a workaholic, Marvel M. Logan had arrived at the United States Senate and was shocked at what he considered to be the inactivity there. One newspaper in Kentucky recalled Logan “loved to work and he worked with telling effect … he in fact worked himself to death in the Senate.”

So, too, did M. M. Logan love the law. After his death, it was revealed he had been offered a highly lucrative job with a New York law firm, which would have paid him far more than the salary he received as a senator. Logan turned down the job quickly, saying he was content and wished to continue his work as a public servant.

Rotund with a head of shaggy hair, M. M. Logan was described by TIME magazine as a “quiet, kindly, able Southern judge.” Physically, the news magazine referred to the Kentuckian as “baggy-kneed” and “baggy-faced.” The premier news magazine of its day, TIME thought Logan a “pious” man who “wouldn’t harm a flea.” “A peace-loving, Sunday-school going ex-judge” who possessed “a nose of such W. C. Fieldsian proportions that he was once described as ‘looking like a rhinoceros crashing through a grass hut.’”

Marvel M. Logan came to the U.S. Senate after a period of time when the Bluegrass State had been represented by Republicans during the era of the 1920s. Logan arrived just as the Great Depression deepened, causing joblessness, hunger, deprivation and want throughout the nation.

Marvel Mills Logan had been born on a farm near Brownsville, Kentucky. Eventually, Logan studied the law inside the firm of Wright & Sturgeon and passed the bar exam in 1896. At age 21, M. M. Logan embarked upon his political career by being elected as chair of the Edmondson County Democratic Party, but it was the legal ladder that provided M. M. Logan with the means to rise through the ranks and sit in the highest councils of state and federal governments. Logan was also aided in his rise in politics through his affability as well as his penchant as a joiner. M. M. Logan was active in a host of fraternal organizations such as the Order of Odd Fellows, the Masons, the Elks, and Woodmen of the World.

Logan was the county attorney for Edmondson County briefly before becoming an assistant state attorney general. Logan was elected state attorney general in 1915 and served for two years before resigning his office. Logan had resigned to serve as the chair of Kentucky’s State Tax Commission for an equally brief period of time. In 1918, M. M. Logan moved to Louisville, Kentucky, and hung out his shingle as a lawyer. Four years later, Logan moved again to Bowling Green, where he and his wife lived in a remarkably modest bungalow-style cottage. The former attorney general still received calls to serve the people of Kentucky as a member of the state board of education and other, lesser-known state entities. Eventually, Logan was elected to the Kentucky Court of Appeals in 1926 for an 8-year term and served as chief justice in 1930.

In 1930, Marvel M. Logan was the Democratic nominee for the United States Senate to face GOP incumbent, John M. Robsion, who had been appointed after Senator Frederic M. Sackett resigned to accept an appointment as America’s ambassador to Germany in January of that same year. Robsion was no mere caretaker, but rather an experienced legislator who had long represented Kentucky’s 11th District. Logan only beat Senator Robsion in the general election by 27,538 votes out of approximately 640,000 ballots cast.

As a member of the United States Senate and a Democrat, M. M. Logan was highly skeptical of President Herbert Hoover’s efforts to stem the suffering wrought by the Great Depression. As might be expected, Senator Logan was a firm supporter of Franklin Roosevelt and most of the New Deal during the First Hundred Days. In fact, Senator Logan was so loyal to the Roosevelt Administration, he backed FDR’s plan to pack the U.S. Supreme Court to the very end. Indeed, Logan was one of the few champions of Roosevelt’s court-packing bill in the Senate. Yet there were times when M. M. Logan refused to go along with some New Deal measure and never hesitated to speak his mind.

Senator Logan’s background as a jurist and his seat on the Senate Judiciary Committee made him one of the more important leaders in the fight to enlarge the Supreme Court. M. M. Logan made one of the primary speeches supporting FDR’s legislation and sat through the endless hearings cross-quizzing a legion of witnesses. When Majority Leader Joe Robinson of Arkansas, who was the moving force to enlarge the Supreme Court inside the Senate, died unexpectedly, Senator M. M. Logan made the motion to put the court-packing bill to sleep.

Like many other Southern-oriented Southerners, Marvel M. Logan was a firm supporter of Franklin Roosevelt’s foreign policy and voted to alter the neutrality bills accordingly.

In politics, tides rise and ebb. Yesterday’s burning issue may have burned itself out, only to be replaced by some new question. Eras come and go. In 1935 one of the best natural politicians assumed the governor’s office. A. B. “Happy” Chandler could bring laughter or tears, depending upon the occasion and would sing “My Old Kentucky Home” at the drop of a hat, a tradition he continued throughout his long life. Governor Chandler, consolidating his power, sponsored a candidate against Senator Logan in the 1936 Democratic primary. That opponent was a formidable figure; a former governor and United States senator, John W. C. Beckham had the backing of the Chandler administration in a crowded race with no less than five candidates tussling for the nomination. Senator Logan only barely eked out a victory, winning by a scant 2,385 votes. The difference between Senator Logan and former Governor Beckham was a fraction; Logan received 39.94% of the vote, while Beckham won 39.41% of the vote. Chandler tried to topple Majority Leader Barkley in 1938, running against the incumbent himself. That time the state machine buckled under the pressure of the federal government and the full weight of support by President Roosevelt for Barkley. Besides, Alben Barkley was too deeply entrenched to be beaten, even by a talented politician like Happy Chandler.

The general election saw Democrats coalesce around Senator Logan’s reelection campaign and he won easily over former GOP IRS Collector Robert Lucas.

Before he died, Senator Logan felt the bureaucracy was getting out of control. The Kentuckian introduced legislation, the Logan-Walter Bill, which, if passed, might not be more than a “fleabite” to the New Deal, but TIME thought that same bite might very well give the bureaucracy a serious case of “gangrene.” The New York City Bar Association worried the Logan-Walter Bill was “so rigid, so needlessly interfering, as to bring about a widespread crippling of the administrative process.” The Brookings Institute echoed that opinion. Numerous legislative experts and constitutional scholars believed the bill would quite likely create “an endless field day for lawyers.” Still, the House of Representatives passed the Logan-Walter Bill twice by large majorities. The first time, the bill passed 282-97 with two members not voting. The Logan-Walter Bill also passed the Senate, 27-25. President Franklin D. Roosevelt promptly vetoed it. Attorney General Robert Jackson wrote in “prose almost illegally lucid” the Logan-Walter Bill would impose “uniform procedure” on every government agency, which would have the effect “as if we should average the sizes of all men’s feet and then buy shoes of only that one size for the Army.” Jackson was evidently horrified that under the Logan-Walter Bill, any citizen “substantially affected and displeased by a ruling” would have “everything to gain and nothing to lose” by initiating a lawsuit in the District of Columbia Court of Appeals. The attorney general noted should the unhappy citizen lose the suit in the D.C. court, he or she merely had to wait until the offending rule was once again involved and could then file suit in a different court. President Roosevelt insisted the Logan-Walter Bill would hamper national defense measures as well as “flood the courts with unnecessary litigation.” Perhaps more to FDR’s dismay, the president thought the legislation would subject “all administrative action to the control of the judiciary.” Roosevelt said the only thing the Logan-Walter Bill would truly accomplish was “delay, chaos” and “paralysis.” The president finally concluded, “Today, in sustaining American ideals of justice, an ounce of action is worth a pound of argument.”

Senator Logan had been ill for several days when he suffered a fatal heart attack at 2:30 a.m. on October 3, 1939. Only 65 years old, Logan’s death came as a great surprise to his colleagues and the people of Kentucky. The senator’s funeral drew the high and mighty, including Governor A. B. “Happy” Chandler.

The Kentucky Advocate mourned the senator’s passing in an editorial. “In her long history Kentucky has sent many brilliant and splendidly equipped men to the United States Senate, but she never sent a better equipped gentleman than the great man who has just passed away.”

Ironically, it was to be a former foe, Governor A. B. Chandler, who took Logan’s place in the Senate. Happy Chandler resigned his post as governor, allowing Lieutenant Governor Keen Johnson to succeed him. Governor Johnson promptly appointed Albert B. Chandler to fill the vacancy. Apparently, the people of Kentucky didn’t mind as they subsequently elected Chandler in a 1940 special election.

As expressed in his will, Marvel M. Logan was laid to rest in the family cemetery where both his parents and grandparents were buried. He sleeps there to this day.

© 2024 Ray Hill