Burning Down Washington, D.C.

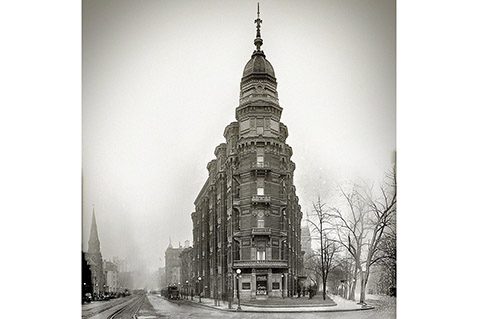

Those cities which are also capitols for their respective countries are always highly cognizant of several things, not the least of which are social status and one’s address. In 1922, one of the more elegant and desirable addresses in Washington, D.C. was Portland Flats, a luxury apartment building. Located in the Thomas Circle neighborhood of Washington, D.C., it was capped by a shining dome and spire reaching into the sky. Some thought it an excellent example of “Victorian decorative exuberance” if not actual “excess.” The red brick, six-story apartment building was a wonder. Even the exterior of The Portland was so lavishly embellished that historian Richard Longstreth thought it was “on a scale seldom matched locally or anywhere else in the country.”

For decades, few congressmen and senators invested in purchasing homes in Washington, D.C. as they remained in the Capitol only part of the year. Most congressmen shuddered at the notion of being thought to live in Washington by their home folks. Edward Weston, a retired banker and investor in railroads from Yonkers, New York, sought to erect The Portland as Washington, D.C.’s first luxury apartment building. Hiring a noted architect (Adolf Cluss), Weston had the apartment house built in two phases and the apartments from the first through the fourth floors were larger and included three bedrooms, a parlor, dining room, bathroom, and kitchen as well as a servant’s room and appropriate storage closets and pantry. Author John DeFerrari, an expert on old Washington, D. C., noted the care of the construction of the building and the meticulous attention paid to its interior. While most of the rooms featured open fireplaces, none of them worked and were meant only to convey the feeling of homeliness. The wood trim in the apartments was oak, cherry, ash and white heart-of-pine, all of which had been hand-oiled and polished to a sheen. The parlors of the apartments on the first through the fourth floors all had especially ornate fireplaces with “rich ebony mantles, ornamental tile borders and hearths” which were “surmounted by beveled mirrors.”

One did not have to reside in The Portland to enjoy its luxury and elegance. Weston spared no expense in building The Portland, which featured no less than three public dining rooms, including one largely for women, which was a custom of the time, all on the ground floor. The corridors intended for the public were arched and tiled in pristine marble.

John DeFerrari notes those living at The Portland enjoyed all of the most modern conveniences available. Each apartment had its own doorbell to spare tenants from hearing unnecessary knocking on doors. Each had a dedicated telephone line that ran to the office of the building superintendent, which was located in the basement. There were also dumb waiters to ferry upward from the laundries, kitchens and storage rooms located in the basement as well.

Despite the unprecedented lavishness of Edward Weston’s Portland, observers at the time were aghast at the notion respectable citizens would deign in live in “tenement houses.” Edward Weston was laughed at, but the investor enjoyed the last laugh. The Washington Post noted, “The Portland is now a gold mine to its owner.” Amongst some of its first residents were several senators and congressmen and the Russian Tsar’s Imperial ambassador to the United States.

As is always the case in such instances, eager developers, seeking to mine their own gold, quickly bought up property and began constructing luxury apartment buildings, hoping to duplicate the success of Edward Weston. By the decade of the 1920s, the newness had worn off the Portland and there was considerable competition to house Washington’s elite. One of its residents in 1922 was Tennessee’s junior United States senator, Kenneth D. McKellar. McKellar had served six years in Congress before becoming the first person ever to be popularly elected to the U.S. Senate from the Volunteer State. McKellar was running for a second six-year term that year and while known for his courtly manners, the Tennessean was also noted for his volcanic temper. Few people would have really been surprised to hear Kenneth McKellar attempted to burn down Washington, D.C. in a fit of pique.

The Washington Times reported on May 1, 1922, a fire of “undetermined origin” had started in the Tennessee senator’s apartment at The Portland. The fire raged and swept through the fifth and sixth floors of the Portland before firefighters were able to contain it. It was a genuine “four alarm” fire which the Times reported necessitated “every available piece of fire apparatus in the downtown section” of Washington, D.C. Mrs. Lynn Glover, who lived in apartment 42 was overcome by smoke and had to be bodily carried from her home to the sidewalk below. Miss Margaret Cummins, the sister of Iowa’s Senator Albert Cummins, was confined to her bed due to illness and was one of the last people to be rescued as the elevator had to be cleared for her to leave. The elevators had been busy ferrying firemen and their equipment throughout the building and to the rooftop of The Portland.

A former military attaché to the Japanese Embassy, K. Youkoyama, along with his wife, smelled something burning around 1:50 in the afternoon. Their curiosity roused, they noted with alarm “thin spirals of smoke creeping beneath the door of their apartment.” The couple fled to safety, although not without carrying “piles of costly Japanese wearing apparel” braving the “dense clouds of smoke to the street.” A gong in the lobby of The Portland served as an alarm notifying residents to leave the building in times of emergency. The gong was sounded.

Mr. E. A. Garvey, a resident of Washington, D.C., was passing by The Portland and happened to notice flames fluttering around the window frames. Garvey hurried inside and told the switchboard operator The Portland was on fire. Chief Watson, having fought a similar fire at Washington’s Willard Hotel a couple of weeks earlier, was taking no chances. That particular blaze had proved to be difficult to extinguish and the chief lost no time in having high-pressure hoses delivered to The Portland.

Firemen were called and the first team of firemen to arrive was so worried the entire building would be consumed by the flames they called for all available help. As might be imagined in times of an emergency, there was some confusion. A massive mirror of epic proportions, 20 feet wide and 40 feet long, fooled some of the firemen, along with some eager reporters, who thought it was an entrance and ran headlong into the mirror, shattering it.

Thousands of spectators stood and watched as firefighters fought the flames and helped people to safety. Women were helped down ladders from their apartment windows by firemen to the streets below.

The Washington Herald reported the following day that firefighters had determined the most extensive damage had indeed occurred in the apartment of Senator McKellar, but the Tennessean shared the large apartment with Captain John E. Tuther of Memphis. It was Tuther’s room that was the most extensively damaged, causing experts to believe the fire had started in his quarters. The flames had burned through the ceiling of Tuther’s room into the apartment above.

The entirety of The Portland had suffered either smoke and or water damage. Whether or not it was because of the losses due to the fire, the owners of The Portland, all of whom were relations of the original owner, Edward Weston, sold it to Harry Wardman. Wardman bought The Portland for $450,000, which would be almost $8 million today.

Harry Wardman was one of Washington, D.C.’s preeminent real estate developers. His projects included hotels, luxury apartment buildings and the like. Wardman’s first real estate development was modest enough; a row of six houses well before the term “rowhouses” had been popularized. Perhaps Harry Wardman’s most memorable project is the Wardman Park Hotel located in the toney Woodley park section of Washington, D.C. Wardman built Wardman Park in 1918, opening the 1,200-room hostelry to the public and it was immediately a great success. Adjacent to Wardman Park, the developer built the Wardman Tower, which became a Washington, D.C. institution. Many of Washington’s high and mighty lived in the apartment building including Tennessee’s Cordell Hull, both during the time he served as Franklin Roosevelt’s Secretary of State and during his retirement. Hull and his wife Frances lived in a very comfortable seven-room apartment that had a working fireplace.

Harry Wardman also built another legendary Washington hotel, the Hay-Adams across the street from the White House. The Hay-Adams Hotel was built upon the site of where the mansions of John Hay and Henry Adams had once sat. Hay, secretary to President Abraham Lincoln as a young man, later became Secretary of State under William McKinley. Hay looked upon Abraham Lincoln as more than a father figure and when the president was assassinated, the young man was believed by his friends and associates to have mourned the loss of Lincoln for the rest of his own life.

A native of Indiana, John Hay was a man of considerable talents and abilities. While working for the New York Tribune, he courted Clara Louise Stone, daughter of Amasa Stone, a banking and railroad magnate from Cleveland, Ohio. Hay was a brilliant editorial writer and it was he who wrote after interviewing Mrs. O’Leary of Chicago (whose cow supposedly started the fire which burned much of the Windy City) “a woman with a lamp who went to the barn behind the house, to milk the cow with the crumpled temper, that kicked the lamp, that spilled the kerosene, that fired the straw that burned Chicago.”

Amasa Stone not only helped Standard Oil (John D. Rockefeller’s company) solidify its monopoly through his railroad holdings but also held large stakes in the steel and iron industries. Stone committed suicide in 1883, which left his daughter and her husband quite wealthy. Hay later commented upon his “strange and tragic fate” at having been near and close to three American presidents who had been murdered in office: Lincoln, James A. Garfield and William McKinley. Deeply depressed by the loss of his son, Secretary of State Hay wrote a friend that he and Mrs. Hay had become suddenly “old” when their child had died. As the secretary’s health deteriorated, Hay wrote a jocular letter to yet another friend, saying “there is nothing the matter with me except old age, the Senate, and one or two other mortal maladies.” He died at his vacation home in New Hampshire of heart disease while still in office.

Henry Adams was, of course, one of the greatest men of letters in American history, memorialized by Harry Wardman for all time in a way Adams might well not have appreciated.

Another iconic Washington hotel built by Harry Wardman was the Carlton, which still stands today as the St. Regis. In fact, the three premier hotels first built by Harry Woodward are all still standing and doing business in Washington, D. C. to this day. During my last visit to Washington years ago, I stayed at the old Wardman Park, which had been renamed at the time. When I was there, it carried the more modest name of the Sheraton Washington, but has since been renamed the Marriott Wardman Park in honor of its original builder.

An immigrant from England who started out as a carpenter, Harry Wardman built up a fortune estimated to be in excess of $30 million (over half a billion in today’s dollars), much of which was lost with the 1929 stock market crash. Wardman continued working until his death from cancer in 1938. Should anyone doubt the power of the American dream, one only has to look at the life of Harry Wardman, a simple carpenter who taught himself to build stairs and became Washington, D.C.’s greatest real estate mogul.

Drew Pearson, the muckraking columnist, more than twenty years later, accused Senator McKellar of having started the fire at The Portland when he was smoking in bed. It wasn’t remotely true, but that never stopped Drew Pearson.