By Ray Hill

The late Howard H. Baker Jr., the first Republican ever to be popularly elected to the United States Senate from Tennessee, has a great claim to being labeled “Mr. Republican” for the modern era. Yet Brazilla Carroll Reece of Johnson City may have a better claim to being “Mr. Republican” for Tennessee during a time when the GOP was distinctly the minority party in the Volunteer State. Like his successor, James H, “Jimmy” Quillen, Carroll Reece was not an orator. Reece spoke quite slowly and methodically, which oftentimes didn’t excite audiences. Yet Carroll Reece proved to be enduringly popular with the people he represented. For one thing, Congressman Reece never stopped campaigning, in or out of office. Reece also concentrated on providing excellent constituent services to the people of upper East Tennessee. The people in Tennessee’s First Congressional District liked and appreciated Reece’s efforts. Carroll Reece was elected to Congress eighteen times by his constituents and his career spanned forty years.

Carroll Reece had been born in the town of Butler, Tennessee and was one of thirteen children of John Isaac and Sarah Maples Reece. B. Carroll Reece worked his way through the Watauga Academy and then Carson and Newman College. From there, Carroll Reece went to New York where he graduated from New York University with honors. Reece made quite an impression, as the trustees of the college noted his ability and offered him a professorship of political economy.

Standing about five feet and nine inches, Carroll Reece had fought in the First World War where he earned the Purple Heart, the Distinguished Service Medal, the Distinguished Service Cross, and the Croix de Guerre with Palm from the French government. After a brief teaching career in New York, Carroll Reece came home in 1920 and ran against Sam R. Sells, the sitting congressman from Tennessee’s First Congressional District.

When Colonel Grant Trent had announced himself a candidate for Congress, Congressman Sells had sneered he would withdraw as a candidate for reelection if “a real soldier” wanted to run. Colonel Trent withdrew and Carroll Reece emerged as a candidate. Sam R. Sells did not withdraw and charged his political enemies had recruited Reece to run against him. The incumbent seemed to campaign less on his record than his personality.

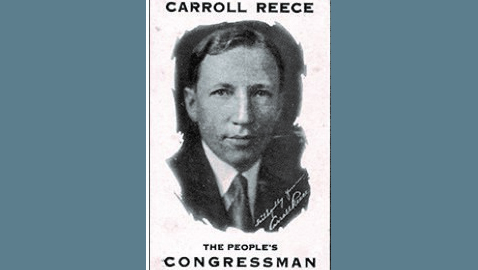

Reece’s campaign featured a picture of the young candidate wearing his uniform, much to the chagrin of Congressman Sells. Sells snorted there was no way he could lose to a candidate who had not lived in the district for years; after a decade of service, Sells felt confident he would be renominated. Carroll Reece campaigned on the theme ten years in Congress should be enough for any man, a slogan that would come back to haunt him later.

During the 1920 campaign, newspapers referred to the young candidate by his military title, as did the Knoxville Journal and Tribune in noting Reece spoke in Bybee, Tennessee in the local high school auditorium. The Journal and Tribune reported, “Lieutenant Reece’s speech was somewhat different from his former ones, in that he sought to answer the opening speech of his opponent which was delivered in Elizabethton a few nights ago…” Reece questioned why Congressman Sells had voted to “exempt excess profit taxes on corporations.” Sells was a successful businessman, owning a lumber company and other concerns. “Why don’t your congressman and mine in explaining how much he made in 1917 and 1918, tell our people how much he made in 1919, and why he voted to exempt these excess profits from taxes?” Reece cried.

The Knoxville Sentinel reported on the race in the First District as growing more heated with every passing day, dispelling “what followers of Sells at first considered a joke” was now a real race. The Sentinel acknowledged Carroll Reece had been “comparatively unknown until a few months” before the primary election and the candidate’s “reputation he made in the recent world war was the first thing to bring him into notice.”

The two candidates for the GOP nomination held a joint debate in Tazewell, Tennessee. It was “court day” in Tazewell and some 500 people in Claiborne County gathered to hear Sam R. Sells and B. Carroll Reece speak and speak they did. Carroll Reece spoke for an hour, while Congressman Sells spoke for an hour and 15 minutes. As might be expected, the candidates tossed the occasional barb back and forth. “Lieutenant Reece says that he is in favor of reducing the high cost of living,” Congressman Sells snorted. “Who in the name of common sense and good judgment is not?” Reece jabbed Sells for paying considerable attention to his business interests, telling his listeners he would devote all his time and energies to serving in Congress. “There is no reason why I should lose touch with the people from whom I sprang, when I am elected to office,” Reece said. “Whatever office is held, the powers of it are from the people, and if I do not render as much service in two years as Sells has in 10, I will not seek reelection.”

Carroll Reece had actually gone to the office of Congressman Sells before announcing his candidacy to visit. It was during the Tazewell debate Reece described his initial conversation with Sam R. Sells.

“Before I made the announcement of my candidacy, I met Mr. Sells on the street in Johnson City with one whom I thought at that time was a mutual friend,” Carroll Reece related to his audience. “After being introduced, I was invited into Mr. Sells’ office where I presume Mr. Sells’ henchmen thought some wholesome advice should be given for the benefit of ‘the boy.’ When we were alone, this is about the way the interview went. We both sat down and Mr. Sells lit a cigar which he stuck in the corner of his mouth at an angle of about 5 degrees. Then, sticking his thumb in the armhole of his vest, and looking out from under his shaggy eyebrows as he looked at me and said, ‘Reece, who are you?’”

Doubtless, that brought some laughter and twitters from those gathered in Claiborne County, Carroll Reece continued with the telling of his tale of his meeting with Sam R. Sells.

“Old Goliath showed that same spirit when he came face to face with David,” Reece said. “What his attitude implied was, do you think that you can oppose me for this office? He knew who I was. Well might he have recalled the days when my father and mother lived in a log cabin which sat within the shadow of his mother’s stately mansion, and when I came to the back door of his house peddling butter and eggs. He thought he could break my spirit and that I would sneak away like a whipped cur. ‘You haven’t a chance to win the nomination,’ he said. ‘I’m in better shape than ever financially to fight competition, and when I get ready to retire I am going to name my successor.’ There was just one thing my friend overlooked and that is you can’t disregard the wishes of a great people in things like this.”

When it came his turn to speak, Congressman Sells did not dispute most of what Carroll Reece said about their first meeting, but insisted he had never insulted the young lieutenant.

The notion Carroll Reece’s candidacy was little more than a joke had evaporated by the time the primary election approached. The Nashville Banner reported “the veteran congressman has a bear fight on his hands” and most Republicans inside the First Congressional District thought it “will be very close.” As the ballots were counted, Congressman Sells issued a statement claiming victory. “I am nominated by a majority of 200 to 300 with Claiborne county yet to hear from,” Sells crowed. “Claiborne will give me a majority of about 400, which will make my lead in the district about 600 to 700. These are absolute facts, the statements of Lieut. Reece’s friends to the contrary notwithstanding.” Yet one Johnson City newspaper claimed Carroll Reece had been nominated by at least 300 votes.

The Kingsport Times carried a banner headline in its August 6, 1920 edition blaring: “Carroll Reece Decisively Defeats Sells in Congressional Race.” According to the Times, Reece had won by more than 1300 votes. A day later, the Chattanooga Daily Times noted the success of veterans in elections all across Tennessee. “The people appear to have taken a great fancy to overseas men in the primary balloting in the state on Thursday,” the Daily Times reported. “Lieut. B. Carroll Reece who served his country faithfully, honorably and with distinguished bravery during the war with Germany, appears to have beaten the veteran politician Sam R. Sells for congress in the First district.” The Chattanooga Daily Times article illustrated just what a feat Reece had accomplished in vanquishing Sam R. Sells, who was described as “one of the bosses of the republican party in East Tennessee” for quite some time. The Daily Times thought Sells “a strong man, too, and a fighter of ability and experience.” Yet the Daily Times pointed out Sells had “a record that savors much of demagogy, hypocrisy and opportunism” which had given Carroll Reece the basis to upset the congressman. The Daily Times noted the similarities between the candidacies of Carroll Reece and Gordon Browning in Tennessee’s Eighth Congressional District.

Browning had challenged Congressman Thetus W. Sims for the Democratic nomination. Sims had been in Congress for twenty-four years and Browning, like Reece, was a veteran of the First World War. The Chattanooga Daily Times thought Browning was “bright, active, progressive and sound on democratic principles.” The editorial described Gordon Browning as direct and straightforward, with no disposition to compromise “with wrong of any kind.”

Reece would go on to win the general election in 1920 while Gordon Browning would lose to Republican Lon Scott, who was also a veteran of the World War. 1920 was a Republican year in Tennessee and many Democrats were swept out of office by the GOP tidal wave. It was the first election in which women could cast their votes for candidates up and down the ballot. Warren G. Harding carried the Volunteer State in the presidential race, while Alf A. Taylor defeated incumbent A. H. Roberts for governor. Congressmen John A. Moon of Chattanooga and Cordell Hull, both of whom had opposed suffrage for women, lost to GOP candidates.

Gordon Browning, stubborn and irrepressible, made a determined bid for Congress once again in 1922 and defeated yet another incumbent, toppling Lon Scott and remained in the U. S. House of Representatives for 12 years before leaving to make an unsuccessful race for the U. S. Senate. Browning served three terms as governor of Tennessee and he and Carroll Reece enjoyed parallel political careers until 1952. Reece remained in office for almost another decade after Gordon Browning had been consigned to private life by Frank Clement.

Once in office, Carroll Reece followed the example set by Senator Kenneth D. McKellar, who stressed service to constituents. The McKellar office was the first modern congressional office to emphasize constituent service in Tennessee. Carroll Reece adopted the same practices as the McKellar office to go the extra mile in attempting to help constituents with problems, large and small. It was a practice continued in East Tennessee in the congressional offices of Jimmy Quillen, as well as Howard Baker, Sr. and John and Jimmy Duncan.

Congressman Carroll Reece became an institution inside his own first Congressional District, but like every officeholder, he was not without political enemies or detractors. Usually surefooted on political grounds, Carroll Reece made one political miscalculation that cost him his seat in Congress. It was an experience he never forgot.