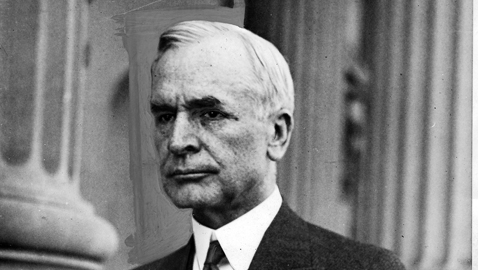

Cordell Hull, for fourteen years the congressman from Tennessee’s Fourth District, had lost his reelection bid in the 1920 Republican landslide. Tennessee had lost three longtime incumbents during the 1920 elections: besides Cordell Hull, Thetus W. Sims of Tennessee’s Eighth District and John A. Moon of the Third District had been beaten. Sims, comfortable in Washington and sixty-nine years old at the time of his defeat, had lost the Democratic primary to Gordon Browning, a young veteran of the First World War. Browning had narrowly lost the general election to Republican Lon Scott. Congressman Moon, like Cordell Hull, had been defeated for reelection by his Republican opponent, Joe Brown. Neither Browning, Hull nor Moon ever stopped running to win in 1922. Moon had already been designated as the Democratic nominee for Congress in 1921 when he suddenly died on June 26, 1921. The sixty-five year old Moon had been ill during his last campaign for Congress and had apparently never really recovered.

The Republicans would be hard pressed to hold their gains during the 1922 campaign, although nobody counted out the irrepressible Governor Alf Taylor. Governor Taylor, despite being seventy-four years old, was an able and entertaining speaker and personally popular. Congressmen Wynne F. Clouse, who had defeated Hull, and Congressman Lon Scott were off and running for reelection. Congressman Joe Brown, who had defeated John Moon, opted not to run again and resume his law practice.

Cordell Hull was determined to regain his own place in Congress and during the interim had been elected Chairman of the Democratic National Committee. That position gave him even more prominence nationally and reinforced the notion with his former constituents that Hull was a national figure while the Republican incumbent was merely another freshman GOP congressman. Hull did not resign his position as Chairman of the Democratic National Committee to begin his own campaign to be elected to Congress; instead, he concentrated upon not only returning to Congress, but also electing as many Democrats as possible in the 1922 election cycle. Hull had kept his political fences mended and had spent more time inside the Fourth District than he had prior to his defeat. Not every Democrat in the Fourth District was ready to simply hand the nomination to Hull by default. A host of ambitious Democrats began to feel out the race, but all of them quickly concluded Hull’s personal organization inside the Fourth District made him the overwhelming favorite for the congressional nomination. Colonel Nathan G. Robertson, a powerful Democrat from Wilson County, was rooting around the edges of the race, as was Thomas G. Baskerville, a prominent Democrat from Gallatin and Sumner County. Baskerville had gotten a taste of politics from having been a delegate to the 1920 Democratic National Convention in 1920. Both Robertson and Baskerville soon dropped plans to run when it became all too obvious most Democrats considered Hull’s defeat not only a travesty, but a humiliation to their own community.

Holding heavy majorities in Congress, as well as the presidency, many Republicans discovered governing was no bed of roses. Republicans, out of power since the administration of William Howard Taft, were clamoring for jobs and appointments and the infighting for those positions was fierce. Longtime GOP Congressman J. Will Taylor maneuvered skillfully to preserve his own personal power and dominance over Republican patronage against his freshmen colleagues. Congressman Clouse tangled with James S. Beasley, Chairman of the Republican State Executive Committee, over patronage. Beasley did little to enhance Congressman Clouse’s prestige when he snapped Clouse had been “nominated for Congress by chance and elected by accident.”

Beasley had added insult to injury, describing Wynne F. Clouse as “the down on a tiny feather in the tip of the wing of a very small hummingbird that was caught on the crest of the Harding – Taylor tornado and swept into Congress.”

Clouse’s fellow freshman Republican Congressman Lon Scott, representing Tennessee’s Eighth District, was also feuding with John Overall and James Beasley over patronage in his own district. Beasley paid a courtesy call on both congressmen during a visit to Washington and reputedly assured both he would support them for reelection, although it did little to smooth out the differences between them.

Many Republicans apparently believed the landslide of 1920 was the dawn of a new era of Republican domination and it was until the Great Depression. It remained to be seen if Tennessee would become a truly two-party state, yet Tennessee Republicans prepared to challenge Senator K. D. McKellar, who was up for his second six-year term in 1922. Rumors abounded that the seventy-four year old Alf Taylor would abandon the governorship to challenge the popular McKellar, causing the hopes of others desirous of being governor to soar. McKellar, who knew something about patronage himself, was not sitting idly awaiting a challenge from the Republicans. A fierce partisan himself, McKellar officially filed charges against John W. Overall, Tennessee’s Republican National Committeeman, for “alleged violation of the civil service act and the alleged selling or trafficking in federal offices in Tennessee.”

Unlike 1920, McKellar would be heading the Democratic ticket and helped to heal the wounds left from a bruising gubernatorial primary between former governor Benton McMillin and attorney Austin Peay of Clarksville. McMillin, seventy-seven years old and the “Old Warhorse” of Tennessee’s Democratic Party, quite nearly won the nomination, losing by a scant 4,018 votes. Peay’s nomination came through the returns from E. H. Crump’s Shelby County where the lawyer won 9,079 votes to 1,732 for McMillin. McKellar had been opposed for renomination by Captain Guston Fitzhugh, a wealthy attorney who was part owner of the Memphis Commercial Appeal. McKellar’s candidacy had been bitterly opposed by his rival Luke Lea, whom McKellar had defeated for reelection six years previously. Lea’s own newspaper, the Nashville Tennessean had regularly assailed McKellar at every opportunity, but the senator crushed Fitzhugh in the primary. Despite the hard fought primary campaign, Democrats entered the fall campaign united.

Cordell Hull toured the Fourth District and if Democrats had tried to woo the votes of newly enfranchised women in 1920, they redoubled their efforts in 1922. Hull paid special attention to female voters during his 1922 campaign. The former congressman urged women in particular to be sure they paid their poll taxes to be able to vote. Throughout the campaign, Cordell Hull campaigned as if he were the incumbent, not the challenger. Well financed and even better organized, Hull entered the 1922 campaign with an air of superb confidence, yet he was careful not to appear to be taking his people for granted.

As Hull completed his first tour of the Fourth District, Congressman Wynne F. Clouse was busy opening his campaign headquarters in his home city of Cookeville. The congressman’s campaign was run by Oscar Clarke of Algood, Tennessee, who had managed Clouse’s winning campaign of 1920. Since then Clarke had become something of a controversial figure, wanting to become Tennessee’s Collector of Internal Revenue. Clouse was not successful in securing the office for Clarke and the latter had to settle for a position as a mere cashier in the IRS office. Complying with federal law, Clarke had to give up his job in the Nashville IRS office to assume management of Congressman Clouse’s reelection campaign.

Clouse was smart enough to realize that he began the campaign as the underdog and following the primary elections, instantly challenged Hull to debate the issues, a challenge the former congressman ignored. The Nashville Tennessean sniffed it was only proper for Judge Hull to ignore Clouse’s invitation to debate as it would be terrible were Hull to neglect “the duties of chairman of a great party to participate in a debate where only his personal fortunes are at stake.” Hull’s refusal to debate his opponent, the Tennessean thought, proved the former congressman was worthy of “the confidence that the Democratic party has reposed in him…” The Tennessean chortled if Wynne Clouse wanted to debate someone, he should debate James S. Beasley.

Tennessee Republicans believed they had fielded a strong and respectable ticket headed by Alf Taylor and Newell Sanders. Sanders had served a brief term in the United States Senate by appointment and was the GOP’s candidate against Senator McKellar in the general election. Still, even the most optimistic Republican held out little hope for Wynne F. Clouse’s reelection to Congress in 1922. National Republicans did not exactly abandon Clouse during the fall campaign and sent in some speakers to aid the congressman’s reelection bid, although none were widely known, especially in Tennessee. When Leslie Shaw made a two-hour stem-winder in Crossville on behalf of Congressman Clouse’s campaign, reporters noticed two thirds of the crowd had melted away before the speech’s conclusion.

Hull had no intention of allowing the Republicans to pummel him once again on his record with respect to veterans. A letter signed by Colonel Harry S. Berry, a prominent Democrat and veteran of the World War, as well as an official of the American Legion, was widely disseminated throughout the fourth District. Colonel Berry stated, “Mr. Hull was at all times favorable towards the payment of adjusted compensation…” Berry went into painful detail to point out the only disagreement Congressman Hull had with the payment of the adjusted compensation was the method of financing it. One means of paying out the soldiers’ bonus was implementing a national sales tax, which Hull did not favor. Cordell Hull’s preferred method of financing the soldiers’ bonus was levying a tax on “war profits.” Berry explained, “There was never any opposition on the part of Mr. Hull as to the claim of ex-servicemen, but only a question as to how the funds should be raised.”

Senator McKellar, who had amply demonstrated his own personal popularity by crushing his opponent in the primary campaigns, came to the Fourth District to make a plea for support by Democrats for gubernatorial nominee Austin Peay. McKellar also paid special tribute to Cordell Hull and urged Democrats to return Hull to Congress. Senator Tom Heflin of Alabama came to Carthage, Tennessee to campaign for the Democratic ticket and his assessment that Cordell Hull was “presidential timber” was met with “prolonged applause” from the audience. McKellar confidently predicted a Democratic victory, saying the statewide ticket would win “by at least 30,000 majority or more in the coming election.” Senator McKellar had been “in half the counties in Judge Hull’s district” and was certain of Hull’s victory in the general election.

Hull’s own speeches were more sedate affairs than that of the colorful Heflin, but the former congressman was greeted warmly everywhere he went inside the Fourth District. When Cordell Hull visited friends in Wilson County, he gathered supporters at the courthouse in Lebanon, Tennessee and complained he was unable to spend as much time in Tennessee as he might like, as he was “being rushed to death” visiting counties all across the country on behalf of Democratic candidates. After stops in two other small hamlets, Hull was on his way back to Washington.

Individual counties inside the Fourth District reported Hull continued to gain ground in his bid to return to Congress. Fentress County was one example where Hull was the beneficiary of support from virtually every Democrat in the county and not a few Republicans who resented some of Congressman Clouse’s patronage recommendations. Clouse had insisted in the appointment of J. D. Wright as postmaster for Jamestown, Tennessee, much to the chagrin of a number of other GOP aspirants who apparently were supporting Hull.

Election Day returned Tennessee to the Democratic column. Governor Alf Taylor lost to Austin Peay by more than 38,000 votes. Senator McKellar beat Newell Sanders by more than 80,000 votes and Cordell Hull won almost 63% of the vote in Tennessee’s Fourth Congressional District. Congressman Clouse was able to carry only five of the fourteen counties while Cordell Hull won huge majorities in the remaining counties.

Cordell Hull was returning to Washington, D. C. to resume his career as a member of Congress.