Frederick Gillet & the Fight for Speaker

The mutiny earlier this year inside the GOP caucus of the U.S. House of Representatives is not new, although it hasn’t happened in a long while. In fact, the last time it did occur was one hundred years ago in 1923. Upon that occasion, it took four days and nine ballots to elect a Speaker of the House.

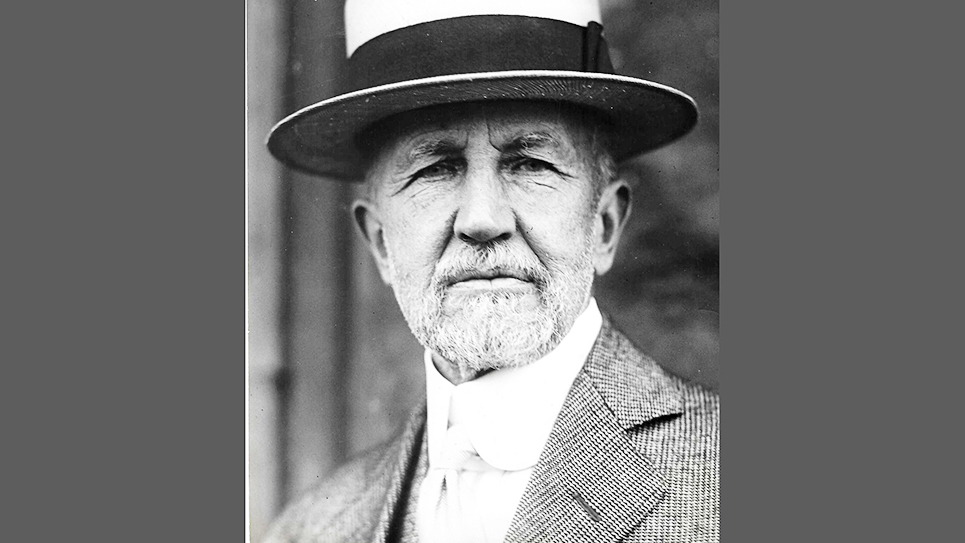

The Speaker of the House at the time was Frederick H. Gillett, a Brahmin from Massachusetts, who had been in the House since 1893. Gillett was first elected speaker in 1919, as the Republicans had won back control of the House of Representatives in the midterm elections of 1918. The Democrats had won a majority in the House in the midterm elections of 1910 during the administration of William Howard Taft. The Democrats elected Congressman Champ Clark of Missouri to be the speaker. Clark was the frontrunner for the Democratic nomination for president in 1912, but while he had a majority of the delegates, he could not win the required two-thirds to obtain the nomination, something his son, Bennett, never forgot. The nomination went instead to Woodrow Wilson, the Southern-born governor of New Jersey. Wilson won the 1912 presidential election because the Republican party was split between President William Howard Taft and former chief executive Theodore Roosevelt, who ran as a third-party candidate.

Roosevelt was one of the harshest and most vocal critics of President Wilson, whom the former chief executive thought was timid and cowardly. When Wilson exhorted the American people to go to the polls in 1918 and treat the midterms as a referendum upon him and his administration, Roosevelt especially exulted in the GOP victory. It was a repudiation of Wilson and his administration. Republicans gained twenty-four seats in the House of Representatives in the 1918 elections, giving them a majority.

Champ Clark was defeated for speaker by Frederick Gillett. Aside from being a patrician, Gillett did not have a dominating or overbearing personality. Gillett loved to play golf and was an amiable fellow.

Woodrow Wilson was felled by a serious stroke, which paralyzed the left side of his body leaving him feeble and incapacitated, a fact unknown to the general public. Still, Wilson wanted a third term in the White House and was bitterly disappointed his party did not nominate him for another term. Yet he was almost surely spared a humiliating defeat as the 1920 election saw a further repudiation of Woodrow Wilson’s administration when the Democratic presidential nominee, Governor James Cox of Ohio, lost badly to fellow Buckeye State resident, U.S. Senator Warren G. Harding. It was the first presidential election in which women could vote following the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment to the Constitution. The 1920 election saw a Republican tidal wave. Even in Tennessee, veteran Democrats were put out of office. Governor A. H. Roberts lost to Republican Alf Taylor; longtime congressman Cordell Hull narrowly lost to a GOP challenger; John A. Moon, who had been in Congress since 1896 lost to his Republican opponent; and the Republicans also won a House seat in West Tennessee, as well as a statewide office, the Railroad & Public Utilities Commission, which was popularly elected. The Republicans gained 63 seats in the U.S. House of Representatives and 10 seats in the United States Senate.

Frederick Gillett was reelected Speaker of the House in 1921. It was following the 1922 midterms when Speaker Gillett encountered difficulty with one wing of his own political party. Republicans lost 77 seats in the House that year, leaving them with a majority of 225 seats to 207 for the Democrats. The Democratic leader of the U.S. House of Representatives was a Tennessean, Finis Garrett, who represented a district in West Tennessee.

Gillett’s path to reelection as Speaker of the House was impeded by the progressive Republicans in his own caucus, not the far-right conservatives. As the House gathered to elect a speaker, Frederick Gillett was ailing with the flu. Prior to the “Lame Duck” amendment to the Constitution, Congress convened to elect a speaker and swear in the newly elected members on March 3rd following the November general election. In 1923, Gillett had been so ill Congressman Phil Campbell of Kansas presided over the House. Campbell had just been defeated in the 1922 election and was himself a lame duck. At noon on March 4, 1923, a Sunday, the speaker’s gavel would fall, marking the adjournment of the 67th Congress. Then a speaker would be elected to preside over the 68th Congress.

A former speaker and the chair of the powerful Ways & Means Committee were retiring at the close of the 67th Congress. Joseph G. “Uncle Joe” Cannon still holds the record for length of service for a congressman elected from Illinois with a cumulative 46 years in the U.S. House of Representatives. Joseph Warren Fordney had helmed the Ways & Means Committee before deciding not to seek reelection in 1922.

There were still partisans occupying the House, but there were also collegial and cordial relationships and friendships between members of differing philosophies and opposing political parties. As the 67th Congress came to a close, members celebrated in song, something that is pretty much inconceivable today. George C. Peery, a future governor of Virginia and incoming congressman from the Old Dominion State, sang a solo, “Carry Me Back to Ol’ Virginny.” Kentucky Congressman Alben Barkley led the singing of “My Old Kentucky Home” and “Dixie” filled the House Chamber as well.

Then began the orations paying tribute to various members who were retiring, either voluntarily or because of defeat at the polls, including a one-term congresswoman, Alice Robertson of Oklahoma, who is worthy of a column of her own. A resolution of thanks to Frederick Gillett was passed, thanking the speaker for his “able, impartial and dignified manner” while presiding over the House.

Unlike “Uncle Joe” Cannon and others before him, Frederick Gillett was not a strong speaker. Indeed, the most capable leader amongst the House Republican leadership was Nicholas Longworth of Ohio, the son-in-law of the late Theodore Roosevelt. Longworth was married to Roosevelt’s headstrong daughter, Alice. Bald, dapper, with a well-groomed mustache, Longworth liked to drink and was well-known in Washington, D.C. for being popular with the ladies; it was the Ohioan who had to largely negotiate with those members of the Republican caucus who were unhappy. With a majority of only seven, the progressive Republicans tried to win concessions from the GOP House leadership.

Nick Longworth worked out a series of concessions granted the progressive members of the Republican caucus in the House, which included allowing a large majority of the House to move legislation out of committees if that bill was being held hostage by a hostile committee chair. That was enough to cause the insurgents to vote to reelect Gillett Speaker of the House.

In 1924, Frederick Gillett, after 32 years of service in the House of Representatives, announced he was running for the United States Senate. The incumbent was David I. Walsh, who was the first Irish-Catholic Democrat to be elected governor of Massachusetts, as well as the U.S. Senate from the Bay State. Walsh was highly popular and could always count on cross-over support from many blue-blood “Yankee” voters in his home state. The 73-year-old Gillett narrowly won the general election, riding on the coattails of President Calvin Coolidge, a former governor of Massachusetts. Walsh’s popularity was such that he unseated William A. Butler, who had been appointed to the U.S. Senate in 1925 following the death of the legendary Henry Cabot Lodge in 1925. Butler had been chairman of the Republican National Committee and appointed to the Senate at the behest of President Coolidge. Yet the wealthy manufacturer lost the 1926 general election to David Walsh.

During the 1928 presidential campaign between Republican Herbert Hoover and Democrat Al Smith of New York, it was Senator Frederick Gillett who had planted the “seed” about Mrs. Smith’s being First Lady, should her husband win the presidency. Al Smith was a self-made man and neither he nor his family were ever to be mistaken for patricians. Speaking at the Hotel Kimball in Springfield, Massachusetts, to a gathering of Republican women who were working in the campaign, Senator Gillett told them of the “charm, culture and intelligence” of Lou Hoover, wife of GOP president candidate Herbert Hoover. According to TIME magazine, Gillett told the women, “It is at gatherings like these that we must sow the seeds which will win the election.” Following that comment, Senator Gillett proceeded to discuss Al Smith’s appeal “to a certain class or element of citizens.” Senator Gillett added, “Of course I cannot say very much of Mrs. Smith, because I have never known her, but if the contest were between Mrs. Hoover and Mrs. Smith…” Gillett let his voice trail off. A reporter covering the event for the Springfield Republican, a newspaper that lived up to its name, noted the women applauded the senator with enthusiasm.

That reporter was George Pelletier, who promptly visited Gillett and asked the senator if he wished to finish the sentence. Gillett replied he couldn’t recall what he had said exactly and dismissed it as unimportant in any event. Quite likely, the comment would have probably never gone beyond the pages of the Springfield Republican had not the New York Times published it in an editorial. That same editorial lambasted Frederick Gillett with a variety of adjectives, including denouncing the senator’s “vulgarity and stupidity” as well as his “execrable taste,” while lamenting Gillett’s “political blunder.” The Times editorial wailed about Gillett’s “folly,” ‘impropriety,” which it thought “unchivalrous” and “offensive” and denounced it as “underground propaganda.”

The scathing editorial brought a response from Senator Gillett who promptly sent a letter to the editor of the Times. “The words and insinuation you ascribe to me I neither uttered nor conceived…” The senator insisted the newspaper had “been imposed upon… by a gross perversion and distortion of a harmless remark.”

Reporter George Pelletier saw Gillett’s letter to the editor and fired off one of his own. Pelletier related his having paid a call on the senator and their subsequent conversation. “It is the first time the charge of ‘misquoted’ has been aimed at me,” Pelletier raged, “and it is baseless, even though it comes from a Senator.”

By 1930, Gillett appeared to be facing a serious challenge inside the GOP primary and was 79 years old. Senator Gillett retired. One reporter thought Frederick Gillett, despite having served in both houses of Congress for quite nearly 40 years, was less a politician than a philosopher in politics. The newsman thought Gillett was more like a college president than an elected official. Gillett possessed the good manners expected of his class and “was the graceful and courteous gentleman whose soul disliked and whose mind never well comprehended, the rough and tumble of politics,” the journalist remembered.

For one who had spent so long in the chambers of both the House and Senate, Frederick Gillett was no orator. In fact, he was rather an “inept” speaker during debate. Yet Gillett was well-liked by his colleagues. Progressive Republican maverick William E. Borah of Idaho, when told of Gillett’s death in 1935, quickly replied the late speaker was “one of the most likeable men” he had ever known. When as Speaker of the House, Frederick Gillett, without outwardly displaying any anger or raising his voice, had delivered a scathing denunciation from the speaker’s chair, to Texas Congressman Thomas Blanton for having supposedly put “obscene material” into the Congressional Record, the Texan was so shaken he had “stumbled from the floor to keel over, partially unconscious, in the House lobby.”

Frederick Gillett preferred to remain in the House and serve as speaker, but President Coolidge thought him the candidate best able to beat Senator David I. Walsh. Gillett did as the leader of his party asked. Above all, Frederick Gillett was a loyal Republican.

© 2023 Ray Hill