‘Sons of the Wild Jack Ass’

George H. Moses of New Hampshire

By Ray Hill

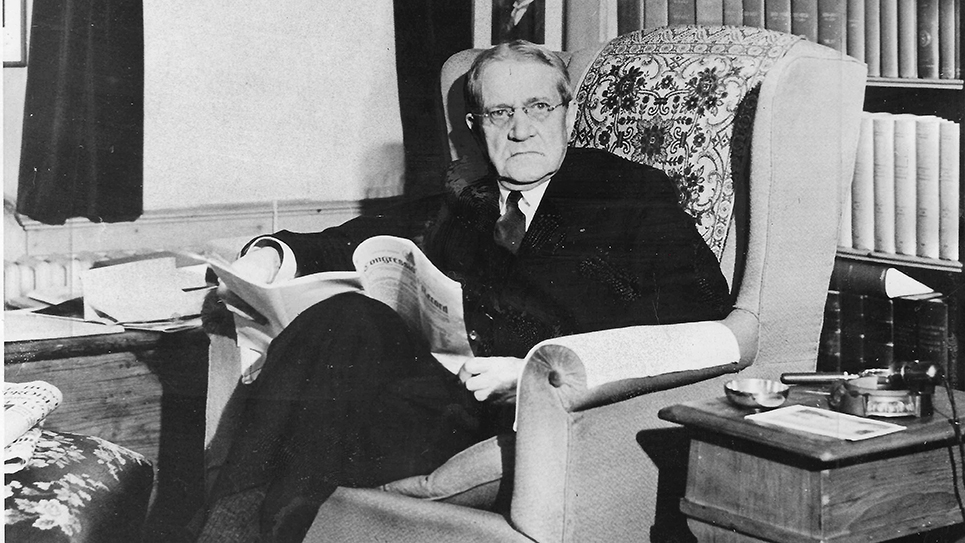

There was a time when George Higgins Moses was one of the most powerful members of the United States Senate. A partisan Republican with a tart tongue, Moses was thought to be the spokesman of Eastern Republicans and “certainly one of the three highest figures in the Republican party organization,” according to the most widely read news magazine of its day, TIME. Moses rose to be the President Pro Tempore of the United States Senate where he “made some of the elder Senators dizzy by the dispatch with which he kept the Senate machinery going.” George H. Moses looked the part, wearing rimless round glasses, looking as dour as a hellfire and brimstone preacher with his hair severely parted in the middle. Perhaps the only hint of whimsy hidden deep within the being of George Moses was the jaunty bowtie he usually wore. Yet there had been a time when Moses had been called “the most exciting man in American public life.”

Throughout his time in Washington, D.C., George H. Moses gained a reputation for saying what he thought, as well as being fearless in his political independence. Moses was also acknowledged as one of the shrewdest political minds of his time. Having been a reporter, Moses knew how to turn a pungent phrase to the delight of newsmen. One of those phrases came from a speech Senator Moses made in Boston where he was highly critical of a farm coalition comprised of Southerners and Midwesterners whom he dismissed as “sons of wild jackasses.” The senator’s remark brought a firestorm of criticism from both regions and Moses was not moved one iota. Indeed, Moses snapped he was not in the least sorry for having used the phrase. When a colleague rose on the floor of the United States Senate and attempted to take Moses to task for the offending turn of expression, the New Hampshire solon retorted, “If a more fitting phrase for this gyrating crowd that is running the Senate can be found, I’ll adopt it.”

When friends urged him to accept the vice-presidential nomination, Moses refused saying the post turned its occupant into “a cipher.” Moses was keen in debate, much feared by opponents for his sharp wit.

Moses had grown up in Maine and New Hampshire and enjoyed an excellent education, having attended Phillips Exeter Academy and Dartmouth College. After graduating, Moses joined the staff of the Concord Monitor, becoming the editor of the newspaper. The young editor became interested in politics and when David Goodell was elected governor, Moses became the governor’s secretary (chief of staff). When the governor left office, Moses returned to the newspaper business, working as a reporter and chief editor for the Concord Evening Monitor until 1918. Throughout that time, George H. Moses was active in governmental affairs in New Hampshire as well as the Republican Party. In 1908 Moses was selected as a delegate to the 1908 GOP National Convention, which nominated William Howard Taft for the presidency. The newly elected president rewarded the newsman by appointing Moses to serve as America’s ambassador to Greece and Montenegro. Moses occupied the post of United States Minister to Greece and Montenegro for Taft’s four-year term of office, returning to New Hampshire in 1913. As minister to Greece and Montenegro, Moses witnessed the first shots fired in the Balkan War while out on an early morning ride.

George H. Moses was once again a delegate to the 1916 Republican National Convention, which nominated Charles Evans Hughes, former governor of New York and an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, as its presidential nominee. When 81-year-old U.S. Senator Jacob Gallinger died, there was a special election in 1918 to determine his successor. George H. Moses became an active candidate and was the Republican nominee for the Senate. New Hampshire was ordinarily a Republican state, but there was a very active Democratic minority and the general election was close. Moses eked out a very narrow victory, winning by 1,070 votes.

Two years later, Moses ran for the full six-year term and faced a credible opponent in Raymond B. Stevens, who had been elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1912 when the Republican Party was hopelessly divided between President William Howard Taft and his predecessor, Theodore Roosevelt, who was running as the candidate of the Progressive Party. Moses had adapted to senatorial life well and concentrated upon rendering the many services constituents expected from their United States senators. Moreover, 1920 was a Republican year and Moses was reelected easily, winning better than 57% of the ballots cast.

No outspoken individual in politics will ever be universally popular, even inside his/her own political party and George H. Moses was no exception. A bitter rivalry had developed between Moses and Governor Robert P. Bass, who challenged the senator in the 1926 GOP primary. Bass tried hard to paint Moses as not having sufficiently backed the policies of President Calvin Coolidge, while the senator serenely campaigned on his record. The campaign was hard fought, and Moses won a decisive victory. Senator Moses was at the peak of his personal popularity with the people of his state, and he won the general election with more than 62% of the vote. George Moses was the only senator elected during the Harding landslide of 1920 to better his percentage six years later.

While in the Senate, Moses was adamant in his opposition to participation by the United States in the World Court and the League of Nations. Highly suspicious of foreign entanglements, Senator Moses had been against the proposed naval limitation treaty in 1930.

1932 proved to be a daunting year for most Republican candidates, something Senator George H. Moses recognized. The hardships and deprivations imposed by the Great Depression had inflicted terrible suffering upon much of America and Moses understood many voters had tired of the Hoover Administration and looked to the Democratic candidate, New York Governor Franklin D. Roosevelt, for some kind of hope for a brighter future. Moses faced a significant opponent in Democrat Fred Brown, who had been a popular governor. Senator Moses never tried to run away from his party label and campaigned upon his record. It was almost enough. Fred Brown edged out George Moses by 2,117 votes.

Consigned to private life following his defeat, Moses candidly assessed himself as “only of nuisance value to the Republican party.” The former senator still had thousands of friends throughout the Granite State, many of whom urged him to try and return to the United States Senate. Moses was a constant presence at GOP events throughout the Granite State following his involuntary retirement from the U.S. Senate. When Republicans gathered in January of 1935 to honor Governor Styles Bridges, the Portsmouth Herald noted the former senator “received a remarkable ovation” when he rose to speak.

When New Hampshire’s other U.S. senator, Henry W. Keyes, opted not to seek reelection in 1936, Moses announced he would run once again. The former senator persisted in seeking the GOP senatorial nomination even though it was clear Governor H. Styles Bridges would also be a candidate. The 67-year-old former U.S. senator faced the youthful 39-year-old governor inside the GOP primary. The contest for the GOP senatorial nomination became the most closely watched election in New Hampshire in 1936.

Supporters of Governor Bridges were outraged when the former senator received an endorsement from ex-President Herbert Hoover. Hoover had sent a letter to former Governor Huntley Spaulding, which stated the former chief executive’s belief it “would be a great thing for the country” if New Hampshire voters returned George Moses to the U.S. Senate. Hoover cited Moses’s experience and abilities “in these most difficult times” as reasons for returning him to the upper chamber.

A third candidate, William J. Callahan, also sought the GOP senatorial nomination. Callahan was a supporter of the plan pushed by Dr. Francis Townsend for the federal government to provide every senior citizen with $200 monthly (the equivalent of almost $4,500 today), which had to be spent the same month it was received. Seventy-eight years old and a crank, Callahan momentarily roiled the senatorial contest when he accused George H. Moses of having offered him money if he would quit the race and leave the field open. Callahan claimed Moses had offered to allow him to “name any figure” as the price of his withdrawal. Moses bluntly called Callahan a liar and denied the allegation, which virtually nobody took seriously.

George H. Moses remained the same prickly, blunt-spoken man he had always been. When queried by labor leaders about his stand on the strike provision of the Esch-Cummins Bill, the former senator instantly said, “I’m for it.” The Central Labor Council informed Moses they would work to defeat him. Moses replied, “If my stand on the Esch-Cummins bill is the reason for my defeat, I shall glory in that defeat.”

Bridges pointed to his record of two years as New Hampshire’s governor, while Moses campaigned on his 14 years in the U.S. Senate. Moses dismissed Bridges as “Little Boy Blue” as he moved across the state, while Bridges stressed his “forward-looking” campaign for the future. In the end, New Hampshire voters looked to the future rather than over their shoulders back to the past in selecting their senatorial nominee.

Moses watched as the election returns dribbled in while in Manchester, New Hampshire. Bridges took the lead and kept it. When it was obvious to everyone else, the former senator stubbornly refused to concede the election. As Moses left the campaign headquarters to return home to Concord, reporters crowded the candidate asking for a statement. “Not yet, not yet,” Moses replied.

Styles Bridges won the contest by better than 13,000 votes, while Moses polled just under 40% of the ballots cast. George H. Moses knew his time in elective office had come to an end and his political career was over. While 1936 was a terrible year for the Republicans nationally and President Roosevelt carried New Hampshire in the fall election, Styles Bridges won the senatorial contest and remained in the Senate until his death in 1961.

Moses was elected as a delegate to New Hampshire’s Constitutional Convention in 1938 and the individual delegates promptly elected the former senator as president of the convention by acclamation. George Moses immediately suggested that one revision of the Granite State’s Constitution should address the heavy taxation placed upon real estate.

After his loss inside the Republican primary in 1936, friends and admirers still nudged the former senator to run for public office. Moses always replied with the same answer: “Why should a man with a bum ticker fuss around with things like that?” Increasingly, Moses moved out of the limelight into the comfort of his Concord home, relishing the fact he would “never again to be in a given place at a given time.” The former senator kept up a voluminous correspondence and enjoyed his status as one of New Hampshire’s senior statesmen.

George H. Moses embarked upon the last campaign of his long career in 1944 when he ran for delegate at large to the Republican National Convention from the Granite State. Moses demonstrated he was still held in high regard by most New Hampshire Republicans, running just behind Governor Robert O. Blood and former Governor Huntley Spaulding. Both Moses and Spaulding ran as “unpledged” candidates, meaning they were not pledged to vote for any particular presidential aspirant. Moses also became the honorary chairman of Mayor Charles Dale’s campaign for governor of New Hampshire in 1944.

For the last year, Moses had been unwell and had only recently returned home from a stay in the hospital, hoping to celebrate Christmas in his own house. The former senator died the night of December 21 from a heart attack. Moses’s wife and only child, son Gordon, were with him when he slipped away.

© 2024 Ray Hill