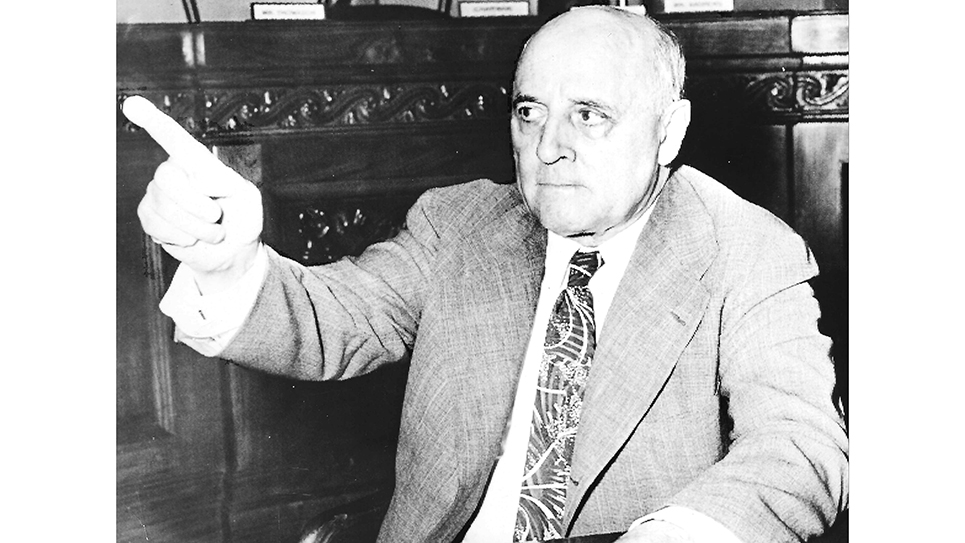

George Holden Tinkham of Massachusetts

One of the most interesting aspects of the U.S. House of Representatives is the fact that it really is the People’s House. The framers of the Constitution intended it to be the People’s House and they succeeded. Some districts send colorless, albeit hardworking, burgermeisters to Congress who have done a solid job in some local jobs. The various personalities form a body of the whole and there are always those more colorful representatives, some of which are truly prized by their own constituency, perhaps as much for their respective quirks and eccentricities as not. During his time, there was hardly any congressman more colorful than George Holden Tinkham of Massachusetts.

Bald with a thick beard, Tinkham was described toward the end of his congressional career by writer Will Lang for one of the most popular magazines of the day, Life. “The startling character of the Congressman is not diminished by his appearance,” Lang wrote. “He is round, low and squat. He clings to the belief that clothes too well-pressed or brushed denote the effete modern, at best the hot spot. The baldness of his shiny pate finds ample compensation in a full spade beard.”

A Republican, the personally wealthy Tinkham was, according to Will Lang, “above all an individualist and non-conformist.” Lang thought the Massachusetts congressman was “a living remembrance of John Quincey Adams” and “Brahmin Boston and the uncompromising past of New England.”

Will Lang acknowledged the point made about the People’s House, noting states and districts had sent to Congress “such oddities as a sideshow barker, a dentist, an All-American football player and a dude rancher. . .” Amongst those “oddities,” Will Lang thought, “’Tink’ is a joyous museum piece.”

George Holden Tinkham was certainly an oddity. Like John Quincey Adams, who consented to sit in the House of Representatives following his having been president on the condition he would never be expected to campaign for the office, so, too, did Tinkham. Instead of campaigning, Tinkham would pack his bags and go off to Africa for one of his favorite pastimes: big game hunting and safaris. In his 27 safaris and two circles of the globe, George Holden Tinkham had “bagged elephant, rhinoceros, water buffalo, zebra, hartebeest, cheetah, ibex and oryx.” Various artifacts from Tinkham’s adventures littered the congressman’s Washington apartment; elephant tusks, leopard skins, pelts and heads, as well as a very large stuffed cobra and its nemesis, a stuffed mongoose.

The furnishings of Congressman Tinkham’s apartment matched the décor of his collection of deceased animals. Upon visiting Tinkham, Will Lang marveled at the “Tibetan textiles, Java silver, a Burmese lacquered table, brassware from Ceylon, a Cashmere table made of wood pulp and ‘light as a feather’.” A figurine of a nude woman, an example of German Neuart, was a particular favorite of the Massachusetts congressman. Nor was Tinkham’s bedroom any less spectacular than his sitting room. Tinkham slept in a “beautifully carved Indian bed” with a Cashmere bedspread. Heavy tapestries from China, India and Japan covered the walls of the congressman’s apartment.

“One inch inside my door,” Tinkham observed to Will Lang, “and you’re inside Africa and Asia.” Not surprisingly, when George Holden Tinkham first went to Washington, D.C., in 1915, he had difficulty finding an apartment to accommodate himself and his collection. Finally, the manager of the Arlington Hotel agreed to rent the congressman an apartment with but one condition: he leave when his time in the House was over. By 1940, George Holden Tinkham had outlived the management with whom he made the agreement. Not even the federal government could budge Tinkham from his apartment. In 1935 the U.S. Resettlement Administration, one of the New Deal’s many “alphabet agencies,” had taken over the Arlington Hotel and tried to put Tinkham out. The wealthy bachelor pointed to his unusual lease agreement and the fact he remained in Congress. “They can’t resettle me,” Tinkham exulted.

Indeed, not even the government had a key to the Massachusetts congressman’s apartment; Tinkham kept possession of the sole key to his abode. Tinkham swept past the two uniformed guards of the former hotel and chortled, “I have almost as good protection as the president.”

Tinkham’s wealth and unusual appearance were not ignored by political opponents seeking to replace him in Congress. One opponent referred to Tinkham as “Nimrod,” which did nothing to forestall the congressman’s usual big majority at the ballot box.

George Holden Tinkham, first elected to Congress in 1914, served through the decade of the 1920s when the Republicans occupied the White House and enjoyed majorities in both the House and the Senate. As time marched on, Tinkham did not. George Holden Tinkham’s favorite role seemed to be that of the loyal opposition. As Will Lang wrote in his profile of the Massachusetts congressman, Tinkham was “against internationalism, pacifism, feminism and the New Deal” of Franklin Roosevelt. As to the question of reform, Congressman Tinkham thought it an abomination. The Bay State lawmaker bitterly fought suffrage for women and prohibition. Tinkham tangled with those church denominations that most stoutly pressed for prohibition laws. For particular opponents, Tinkham gave the names of those opponents to various stuffed heads on his walls. One was christened “Andrew Volstead,” the author of the prohibition law, while another was named for Methodist Bishop James Cannon.

A man of unshakable and strong opinions, Congressman Tinkham conjured strong adjectives for those with whom he disagreed at a time when the public discourse was usually far more polite than today’s exaggerated jabs. The League of Nations was, at least to George Holden Tinkham, “thin-blooded” rather than “red-blooded.” The World Court was simply “wishy-washy.” Colonel Edward M. House, the great friend of President Woodrow Wilson, was “un-American.” Ambassador Walter Hines Page was “traitorous.”

George Henry Tinkham, the congressman’s father, was a wealthy Bostonian, who tried to nudge his son into becoming a professor of history and saw to it that the younger Tinkham was superbly well-educated. After graduating from Harvard University’s School of Law, Tinkham ran for and won a seat on the Boston Common Council, representing the city’s wealthy Back Bay area. Tinkham was elected as a member of Boston’s Board of Alderman where he gained notoriety for exposing corruption. Tinkham tired of politics and took a sabbatical for eight years before being urged to run for the Massachusetts legislature. That led to Tinkham running for Congress as the GOP nominee while Democrats were split. George Holden Tinkham squeaked into office by 1,600. Tinkham, for all his eccentricities, concentrated upon constituent services, rendering every courtesy and assistance to those who lived in his district. The congressman maintained a district office on Pemberton Square in Boston where twenty to forty people daily waited to see Tinkham’s secretary to seek help “in getting jobs, wooden legs, spectacles, second-hand clothes or just plain handouts.” The congressman’s annual $10,000 salary (more than $217,000 today) was usually dispensed inside Tinkham’s district. As Will Lang wrote, “few go away disappointed” from Tinkham’s congressional office.

Congressman Tinkham’s personal popularity was also due to his diligence in representing the folks back home. Tinkham had sent more than a million pieces of information and literature in a single year. The congressman’s personal mailing list, confined solely to the women of his congressional district, numbered 77,000. For those baffled as to why Tinkham would send Christmas cards only to the women of his district, he explained he had found only women paid any attention to such gestures. Every election year, Congressman Tinkham sent a letter to everyone he had assisted with something as a reminder. No letter ever mentioned any particular aid or assistance; it was merely a reminder he was up for reelection and he would continue to do his best for the people of his district.

As is always the case with every successful officeholder, staffing makes all the difference. Miss Gertrude Ryan worked as Congressman Tinkham’s secretary in his Boston office for thirty years. When Miss Ryan first joined his office staff, Tinkham told her, “If you want to succeed in life, two things are necessary – – – intelligence and patience.” Miss Ryan only left Tinkham’s staff to get married after thirty years. Tinkham’s secretary in his Washington office, Miss Grace Hamlin, had only been with the congressman for eighteen years, but he valued her service. “If she ever left me,” Tinkham said, “I guess I’d have to resign from Congress.”

By 1936, one of the best years for Democrats in the nation’s history, FDR carried Tinkham’s district by 21,000 votes, which was quite a feat. Congressman George Holden Tinkham won by a majority of 35,000, running well ahead of Franklin Roosevelt without campaigning personally. Tinkham had only just returned from another foreign sojourn days before the election. As he descended the gangplank of the Europa, the congressman told waiting newsmen, “Dear me! It’s true, there is an election on Tuesday.”

Nor was George Holden Tinkham’s district merely an affluent concave. Quite to the contrary, Tinkham represented a polyglot of a constituency, including half the Blacks living in Boston. The Back Bay Brahmins were mixed with Germans and Irish, all of whom appreciated Tinkham’s resolute stance against internationalism. Indeed, Massachusetts U.S. Senator David Walsh, the first Irish Catholic and Democrat ever to be elected governor and/or to the Senate from the Bay State, was the chairman of the Senate’s Naval Affairs Committee and a strong isolationist. Being suspicious of the British amongst the Irish in Boston and Massachusetts was not considered a failing by tens of thousands of voters. Tinkham was as popular with Blacks, Germans and the Irish in his district as he was with the aristocrats and the wealthy.

The legislation sponsored by Congressman George Holden Tinkham was almost invariably for projects back home in Massachusetts.

As to his leaving the country prior to every election, George Holden Tinkham told reporters he thought it would be more “humane” if all candidates were required to leave the country during the election season. “It would spare everyone a great deal of pain,” the congressman thought, “those who are running and those who are listening.” That notion might be even more popular today than it was then.

Congressman Tinkham’s one concession to personal electioneering was to send out a postcard, thanking individually the people of his district for having returned him to the House of Representatives. Will Lang wrote such a “puny gesture” hardly explained Tinkham’s political success and longevity in Congress. “My district continues to support me because I support the principles upon which this country was founded,” Tinkham insisted.

An implacable foe of internationalism, it was only to be expected George Holden Tinkham would have been a political foe of both President Roosevelt and Secretary of State Cordell Hull. The wily Hull, a master of the rough and tumble politics of his native Tennessee, revealed himself to be a tough verbal opponent. Unlike most of his peers in the Cabinet, Hull would usually appear before the committees of Congress unaccompanied by aides. A veteran of Congress, Hull easily managed even the most hostile congressmen, like George Tinkham. “You say all international law should be dispensed with?” Tinkham bellowed. “My door has been open for eight years and you’ve never darkened it in quest of information,” Hull replied serenely. “We’re supposed to be neutral,” Tinkham reminded the secretary. “We aren’t going to let [neutrality] chloroform us into inactivity.” Tinkham roared at Hull, “But they were little countries and we have 3,000 miles of sea between us, and a fine Navy.” Cordell Hull replied, “I disapprove of your complacency.”

George Holden Tinkham retired from Congress in 1943 after 28 years in the House of Representatives. The former congressman was still traveling at 83. While in London, Tinkham acknowledged, “If I had married, I could not have done all that I have done.” A confirmed individualist, George Holden Tinkham had lived his life as he wished. The former congressman died at age 86 in North Carolina at the home of his sister.

© 2024 Ray Hill