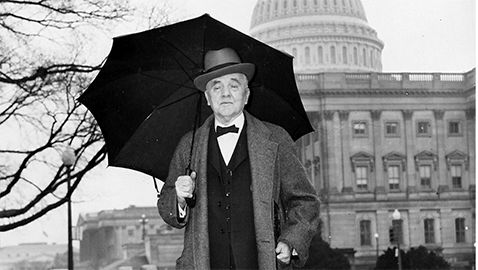

Father of the Tennessee Valley Authority

By Ray Hill

George W. Norris, although a Nebraskan, has a relevance and importance to our community many may fail to realize. Norris Dam and the community of Norris are named for George William Norris. One might think it odd for landmarks in Tennessee to be named for a Nebraska lawmaker. Yet, G. W. Norris has a special significance for our region and state for he was the “Father of the Tennessee Valley Authority.” George W. Norris was born on July 11, 1861 in Ohio, the eleventh child of poor farmers. Norris was still a young child when his father died and his forty-six year old mother was pregnant with her twelfth child. The Norris family had to endure a hardscrabble existence and were quite poor, but Mary Magdalene Norris instilled a strong sense of right and wrong in her son, as well as a strong religious faith. George W. Norris managed to eke out an education and graduated from Valparaiso University with a law degree.

Norris took his law degree and moved to Beaver City, Nebraska. Norris also found love in Nebraska, marrying Pluma Lashley and the couple had three daughters together before Mrs. Norris died in 1901, following the birth of their third daughter. After the death of Pluma Norris, George’s sister hurried to Nebraska to help him care for his daughters. That also allowed Norris to pursue his own political ambitions.

In 1903, George W. Norris remarried and Ella Leonard and her husband had no children born of their union; Ella, a former schoolteacher and principal, was content to be stepmother to the Norris daughters. Ella Norris remained with her husband to his death more than forty years later.

George W. Norris enjoyed a relatively successful law practice and dabbled in real estate. Norris was comfortable enough to build an impressive office building in Beaver City, renting out space to others. The building also housed Norris’ own law practice.

The political career of George W. Norris began with his election as prosecuting attorney for Furnas County and he was later elected to a judgeship. Norris moved from Beaver City to McCook, Nebraska as he felt the latter city was more centrally located in the heart of his judicial district.

1903 was special year in the life of George W. Norris; not only did he remarry, but took his seat in Congress. Norris had been elected in 1902 and served a decade in the U. S. House of Representatives. Congressman Norris was a man who tended to look at issues in black and white terms; those of right and wrong. Originally, Norris had been elected to Congress with the help of the railroad interests. Most everything in the country was transported by rail at the time, making the railroads a powerful special interest. The railroad magnates were both shocked and dismayed when Norris supported a reform proposed by President Theodore Roosevelt to regulate the rates charged by railroads. Norris believed the regulation of railroad rates would benefit the small businessmen of his district, as well as the average consumer. George W. Norris would become the scourge of Wall Street, special interests and big business throughout his long Congressional career.

Congressman Norris studied the issues that interested him and quickly mastered the rules of the House and became one of the more able parliamentarians in Congress. As a young legislator, Norris became increasingly disheartened by the domination of the House of Representatives by Speaker Joseph G. Cannon if Illinois. Norris’ attitude hardened and he became disturbed by the rule of the tyrannical Speaker, who was also deeply conservative. Congressman Norris decided to make an effort to curb the powers of Speaker Cannon. Norris picked his moment shrewdly, launching consideration of his resolution to scale back the Speaker’s power when many of Cannon’s allies were not on the floor of the House. Norris had helped to organize a coalition of insurgent Republicans and all the Democrats who proceeded to defeat “Uncle Joe” and his allies.

Norris’ victory over Speaker Cannon helped to propel him into the United States Senate in 1912. Norris was a strong proponent of direction election of senators, as well as unicameral legislatures. Nebraska remains the only state in the nation without two legislative bodies.

George W. Norris was an isolationist when he entered the United States Senate in 1913. There is a common misconception that most isolationists in Congress were also reactionaries or mossback conservatives. The fact is most of the isolationists were liberals and progressives. William E. Borah of Idaho and Hiram W. Johnson of California ,Henrik Shipstead of Minnesota, and Robert M. LaFollette of Wisconsin were all progressive Republicans. Isolationism was not confined to one political party and there were powerful Democrats who were rabid isolationists. David I. Walsh, the first Irish Catholic ever to be elected governor and United States senator from Massachusetts loathed the British Empire and was an isolationist. Burton K. Wheeler of Montana was so progressive he had been denounced as a radical socialist or worse and was fiercely isolationist. Bennett Champ Clark, son of the late Speaker of the House Champ Clark of Missouri, was one of the leading spokesmen in the U.S. Senate for isolationism.

The Midwest had a strong tradition of isolationism as well as a significant population of German immigrants. George W. Norris was one of six senators who voted against American entry into World War I. Robert LaFollette, Asle Gronna of North Dakota, both Republicans and progressives, joined Norris in voting against war. Democrats William J. Stone of Missouri, Harry Lane of Oregon and James K. Vardaman of Mississippi also voted against a declaration of war against the Central Powers of Europe. Many voters in states represented by the six men were outraged their senators had voted against the war. The senators were reviled, burned in effigy and Senator Lane was facing an effort to recall him from office when he died suddenly in 1917. Vardaman had been the most popular politician in Mississippi before voting against war and subsequently lost his reelection bid in 1918.

Senator Norris believed most wars were fought less for territory or other valid reasons and more for profit, due to corporate greed. Norris felt the only people who benefitted from war were the munitions manufacturers and the financiers.

Norris did not alter his isolationist course one single iota and was reelected in 1918. Senator Norris was profoundly opposed to the Treaty of Versailles, which sowed the seeds of World War II. Norris was also deeply opposed to American participation in the League of Nations.

Unlike many of his fellow progressives, George W. Norris was a prolific legislator, although it oftentimes took his years to achieve his goals. Norris tried hard to abolish the Electoral College and was ultimately unsuccessful. Norris was the sponsor of the Twentieth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States, called the “lame duck” amendment. Prior to the passage of the Twentieth Amendment, the president and the Congress took office on March 4, having been elected the previous November, leaving a frequently “lame duck” president and Congress to legislate for four months following the election.

A passionate believer in public power, Norris labored for years carrying bills that foreshadowed the creation of the Tennessee Valley Authority. Norris found himself at odds with Tennessee’s own senator, Kenneth D. McKellar. Senator McKellar disliked several provisions of Norris’ original legislation, which he felt did not help farmers and their need for fertilizer, as well as other provisions, which the Tennessean believed, put the Volunteer State at a disadvantage. Once Norris and McKellar resolved their differences, the Tennessee senator worked hard to pass the Nebraskan’s bill. The two were finally successful, only to see the bill vetoed by President Calvin Coolidge.

Coolidge’s successor as president was Herbert Hoover and Hoover’s candidacy caused Senator George Norris to bolt the Republican Party. Norris endorsed the Democratic nominee, Governor Alfred E. Smith of New York. Smith, a dripping wet Irish Catholic with a pronounced accent, was hardly a popular candidate in the Cornhusker State. Oddly, Norris was himself an ardent supporter of prohibition.

Many Republicans found George W. Norris so distasteful, they went to extraordinary lengths to defeat him in 1930. Those same Republicans induced a grocer of the same name to enter the GOP primary in the hope it would confuse voters. “Grocer” Norris did nothing to help defeat Senator Norris, who won both the primary and general elections easily. In 1932, unchastened, Norris once again refused to support President Hoover, who was largely discredited following the advent of the Great Depression. Courted by the Democratic nominee, Governor Franklin D. Roosevelt, Norris endorsed the New Yorker over Hoover. Senator Norris lent FDR the prestige of his name when he headed a league of progressives backing the governor.

With the election of Franklin Roosevelt, Senator Norris was personally selected to sponsor the bill creating the Tennessee Valley Authority. Norris’ rival, Senator McKellar, a loyal Democrat and enthusiastic backer of President Roosevelt, remembered it as the greatest disappointment of his life.

McKellar harbored some jealousy toward the old Nebraska progressive, yet also gave Norris grudging respect. Like McKellar, Norris employed a relative on his Senate staff. McKellar’s youngest brother, Don, served as his Chief of Staff, while that position in Norris’ own Senate office was filled by his son-in-law, John P. Robertson.

Senator Norris joined with another liberal Republican, Fiorello LaGuardia of New York, to sponsor the Rural Electrification Act, which provided cheap public power for much of rural America. LaGuardia, New York’s “Little Flower”, would go on to become the most celebrated Mayor of New York City.

Norris sought reelection to the United States Senate in 1936, but quickly realized he likely could not win a Republican primary. Senator Norris announced his candidacy as an Independent candidate. Norris faced two former Congressmen in the general election, one a Republican and the other a Democrat. Norris beat them both.

While Senator Norris supported most aspects of the New Deal, he refused to go along when President Roosevelt sought to enlarge the U. S. Supreme Court in 1937. That same year, George W. Norris changed his point of view on foreign policy. Norris had seen a photograph, which was quite famous at the time, of a badly burned Chinese baby crying while sitting in the midst of the rubble of what had been a train station. The train station had been bombed by the Japanese and the baby’s dead mother lay nearby. It became one of the most famous of all war photographs in history, viewed by as many as one hundred and thirty some-odd millions of people. Like many other Americans, George Norris had been both deeply moved and horrified by the picture. Senator Norris minced no words in describing the Japanese aggression in the Far East. According to Norris, the Japanese were “disgraceful, ignoble, barbarous, and cruel, even beyond the power of language to describe.”

The once fiercely isolationist Senator Norris became just as fired in his determination to punish the Japanese Empire. While he had been an isolationist, George Norris was certainly no pacifist. After the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Nebraska senator declared the United States would “burn Jap cities off the face of the earth.”

Widely respected and even revered by many Americans, George W. Norris had intended to retire in 1942 when he was eighty-one years old. Once Senator Norris stated his intention to retire, thousands of people begged him to remain in public life and run one more time. Norris changed his mind and sought reelection as an Independent candidate yet again. Senator Norris had hoped the Democrats would not field a candidate, as he had been quite supportive of the Roosevelt administration. He was disappointed and faced a serious Republican opponent in Kenneth S. Wherry, a glad-handling former mortician. A Democrat entered the race, sure to pull votes from George Norris. The war was not going well for the Allied forces, causing many incumbents political problems. After forty years in Congress, George W. Norris lost.

The loss of his Senate seat stunned and embittered Senator Norris. Norris termed his defeat as a “repudiation of forty years of service.” Norris lamented his rejection by the “people I love.”

Norris had once said, “I would rather go down to my political grave with a clear conscience than ride in the chariot of victory.” Yet when defeat came, George W. Norris had difficulty believing his constituents would turn him out of office.

Senator Norris, with tears in his eyes, plaintively asked, “Why are the people so mad at me?”

Sadly, Senator Norris returned to Washington, D. C. to close his senatorial office and his Congressional career. When asked by one interviewer, Norris summed up his career in Congress by saying simply, “I have done my best to repudiate wrong and evil in governmental affairs.”

President Roosevelt offered the old progressive any number of posts and appointments, all of which Norris declined. The former senator chose to return to his home on Main Avenue in McCook, where he lived out the remainder of his life. Norris kept himself busy by writing his autobiography, Fighting Liberal. Norris’ autobiography sold rather well and was reprinted almost thirty years after its original publication.

The former senator celebrated his eighty-third birthday in July of 1944 and was fatalistic about his own end. Norris had been quite active for a man of his advanced years, but confessed, “I never expected to live this long; this birthday only means it’s getting closer to the end.”

The end was not long in coming. On August 29, 1944, George W. Norris suffered a cerebral hemorrhage, which left him partially paralyzed. Originally, doctors thought there was a “good chance” Norris would recover. Instead, George W. Norris grew gradually weaker and died on September 2, 1944.

Senator Norris’ former home in McCook is now a museum dedicated to his life and career. Yet, the greatest monument to the life of George W. Norris are the many achievements of his long tenure in Congress. Those of us in Tennessee, more than seventy years after George Norris’ death, have more reason than most to be grateful.