‘Martin, Barton and Fish’

Hamilton Fish of New York

By Ray Hill

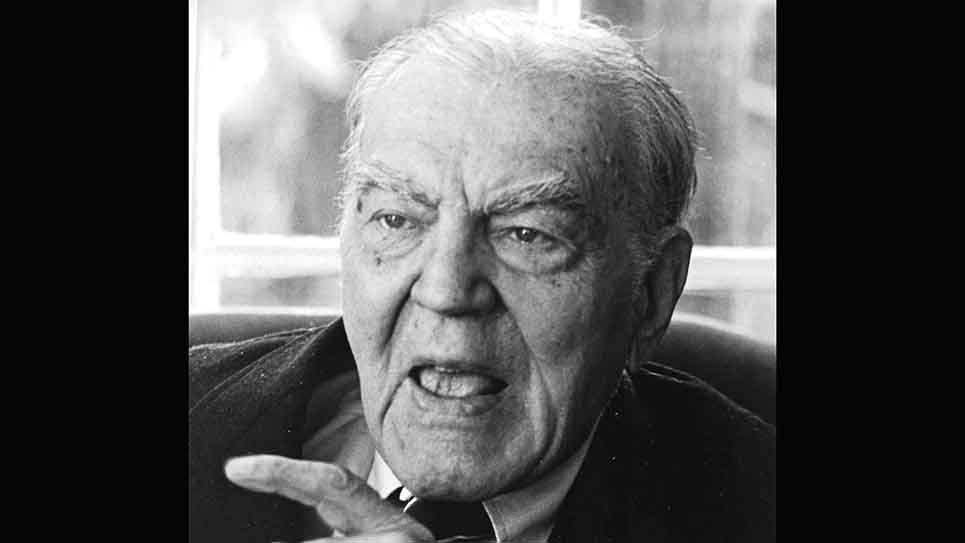

During his time, Hamilton Fish was one of the more controversial members of Congress. A genuine war hero who was roundly hated by internationalists in the United States and was a burr under the saddle of President Franklin Roosevelt. Fish was a constant irritant to FDR, whose mansion in Hyde Park was in the district of Congressman Hamilton Fish. Simply put, Hamilton Fish was Franklin Roosevelt’s congressman. When the long-lived former congressman died, Representative Benjamin Gilman said, “For 102 years, Congressman Fish was not just an eyewitness to more than half our nation’s history, but he was also a major player.”

Fish was one of the better-known congressional critics of the New Deal and internationalism during his nearly twenty-five years in Congress. Described at various times as “fire-breathing,” “acerbic” and worse, Fish was impossible to ignore.

Hamilton Fish was the scion of a family long prominent in New York politics and business. His grandfather, the original Hamilton Fish, had been secretary of state under President Ulysses S. Grant. Fish’s father, Hamilton Fish II, had also represented New York in the U.S. House of Representatives. Fish’s son, Hamilton Fish IV, was also elected to Congress from New York, serving from 1969 -1995. Fish and his wife Grace Chapin Rogers Fish also had a daughter, Lillian, who married the son of publisher William Randolph Hearst. The original Hamilton Fish’s father, Nicholas, was a member of George Washington’s staff. Nicholas Fish named his son after his close friend Alexander Hamilton.

During the First World War, Fish led a battalion of Black soldiers who won acclaim for their heroism. Fish was in charge of the legendary 369th Infantry, an all-Black unit from Harlem. Fish was awarded the Silver Star and the French Croix de Guerre for gallantry in action. When he returned to the States, Hamilton Fish became one of the founders of the American Legion.

As a boy, Hamilton Fish attended the same school his father had near Geneva, Switzerland, the Chateau de Lancy. Later, Fish attended a boarding school in Massachusetts. Fish always described himself as a “B student” and he excelled at various sports. In truth, Fish graduated cum laude in three years’ time from Harvard. Throughout his time in Congress, Hamilton Fish strongly supported veterans and the rights of Black Americans and advocated for the State of Israel.

Hamilton Fish was first elected to Congress in 1920, the first year women had the right to vote in federal elections. Warren G. Harding swamped Democratic nominee James Cox to win the presidency after the eight years of Woodrow Wilson’s administration. Fish assumed office immediately following the election as he had won a special election as well as the regular election due to the resignation of his predecessor in Congress.

Like his friend and colleague Carroll Reece of Tennessee, Hamilton Fish was one of many returning veterans who won a seat in the House of Representatives that year. As times change, so do issues. Fish had been a progressive Republican like Theodore Roosevelt when he was first elected to Congress and became increasingly more conservative over the years.

By the time Franklin D. Roosevelt was elected to the presidency, Congressman Fish was a firm opponent of much of the New Deal. With the rise of the fascist dictatorships of Benito Mussolini in Italy and Adolf Hitler in Germany, war clouds gathered once again in Europe. That, along with the aggressive expansion by the Japanese Empire in the Far East troubled the civilized nations of the world. As war appeared to be imminent, the majority of Americans remained firmly opposed to American intervention. Like many who have witnessed war firsthand, Hamilton Fish was adamantly against American intervention and fought to keep the United States neutral. The New York congressman was one of the loudest voices in Congress who fought President Roosevelt and Secretary of State Cordell Hull to revise the Neutrality Act in 1939.

During his 1940 campaign for a third term, Franklin Roosevelt spoke at Madison Square Garden where he denounced critics of his foreign policy. In his speech, President Roosevelt recalled that the boys in his native Dutchess County used to nail up the hides of foxes and weasels. “Tonight I am going to nail up the falsifications that have to do with our relations with the rest of the world,” Roosevelt told his audience. The president hammered home rearming America, quoting “ex-President” Herbert Hoover, Senators Taft and Vandenberg, and Hamilton Fish.

Roosevelt hit his stride by using a cadence comparable to the children’s rhyme about “Winken, Blinken and Nod.” “Britain would never have received one ounce of help from us – – – if the decision had been left to Martin, Barton and Fish,” FDR cried. It was not long before Roosevelt had the audience chanting “Martin, Barton and Fish” along with him.

Years later, Hamilton Fish told an interviewer he had not been bothered by the speech. “That Martin-Barton-Fish thing was one of the best things that could have happened to me,” the former congressman insisted. “It made me famous all over the country.”

Congressman Fish retorted bitterly, saying Roosevelt was responsible for “lying” the United States into the Second World War. Fish was as fierce an anti-Communist as he was for American neutrality. Like most mere mortals, Hamilton Fish didn’t always exercise the best judgment in some situations. A member of the House Foreign Affairs Committee, Congressman Fish was traveling in Europe well before the Second World War when he was on his way to, ironically, a peace conference in Oslo, Norway. Joachim von Ribbentrop, Hitler’s foreign minister, put his personal plane at the congressman’s disposal. Fish’s political enemies never forgave nor forgot it, especially at election time. Later Fish recalled, “Ribbentrop was an entirely different man than I thought. He was a very charming, good-looking man who talked English as well as I did. He was against the war. Hitler did not want to go to war with England.”

Ordinarily mild-mannered Virginia Congressman Clifton A. Woodrum once torched Fish in a speech on the floor where he declared of his New York colleague, “There is no member of this or any other body who has so unfailingly, so persistently, so regularly, so systematically and so ineffectively opposed the present Administration.”

Still Hamilton Fish never failed to attract attention. The New Yorker referred to New Deal spending as “squandermania.”

Congressman Fish’s Secretary (Chief of Staff) George Hill, a “slight, nervous, bespectacled” man, ran into some considerable legal difficulties. In the midst of an investigation about the lobbying of suspected foreign agents, George Hill had told a grand jury that he had had nothing to do with supposed Nazi agents. A federal court found Hill guilty of lying under oath. TIME magazine, owned by publishing magnate Henry Luce, husband of glamorous playwright and sometime Congresswoman Clare Booth Luce, was a staunch internationalist, a viewpoint ingrained into TIME. The leading news magazine of its day and read by millions of Americans weekly, TIME habitually battered those congressmen and senators who reflected the views of their constituents who wanted nothing to do with foreign wars. One of TIME’s favorite targets was Congressman Hamilton Fish. TIME gleefully related the story of George Hill’s legal woes in a story entitled, “Not Fish, But Foul.” The news magazine noted George Hill and Hamilton Fish had met on the battlefields of France during the First World War and had been close friends ever since. Hill had been summoned before the grand jury to explain what he knew about George Sylvester Viereck, who was believed to be a Nazi agent (he was later convicted of the charge), as well as a shadowy organization called the Islands For War Debts. That same organization was sending out hundreds of thousands of speeches made in Congress by senators and congressmen against American intervention prior to the bombing of Pearl Harbor. Those speeches were sent in envelopes bearing the “frank,” the facsimile of the signature of a member of Congress, allowing it to be mailed for free. An investigation revealed George Hill had sent a truck owned by the House of Representatives to pick up large bags of mail from the Islands For War Debts. Hill denied knowing Viereck or having sent a truck. He was promptly indicted for perjury.

Some of Fish’s comments were also used by his political enemies, who insisted he was sympathetic to the Germans. Despite the best efforts of Franklin Roosevelt and the Democratic Party, both nationally and in New York, Hamilton Fish proved to be almost impossible to beat at the polls. It took several events to finally defeat Hamilton Fish. The Republican machine in New York State was controlled by Governor Thomas E. Dewey, an internationalist who was not an admirer of Congressman Fish. In 1944, the Republican machine backed Augustus W., Bennett inside the GOP primary in New York’s 29th Congressional District. Fish won the nomination with better than 56% of the ballots cast. The general election was a rematch between the two candidates as Bennett was the Democratic nominee, as well as that of several lesser parties, including the Liberal Party, the American Labor Party, and the Good Government Party. Bennett won with 53% of the vote. Considering the formidable political and media forces arrayed against him, Fish made a good showing. Perhaps the most important factor leading to the defeat of Congressman Hamilton Fish was Governor Dewey having Fish’s congressional district redrawn.

If critics thought Hamilton Fish would go quietly into the night, they were seriously mistaken. While they had deprived Fish of his forum inside the House of Representatives, they never succeeded in silencing him. Until the end of his life, Hamilton Fish was a spokesperson against Communism.

Fish’s wife Grace Chapin Fish died in 1960. The former congressman married Marie Blackton in 1966; after her death, Fish married Alice Desmond in 1976. The couple divorced and the former congressman married for the fourth and final time to his personal secretary, Lydia Ambrogio, at age 99. Aside from veteran’s events, Hamilton Fish was a fixture at Harvard commencements until the end of his life. Nor did the former congressman ever lose his interest in public affairs or travel. Fish had a home in Cold Springs, New York, outside of New York City as well as an apartment in the city. Fish maintained an office inside his apartment that was cluttered with memorabilia and reminders of his past and present. Fish kept up a personal correspondence with acquaintances, of which this writer was one. The former congressman was usually attended by his small dog in his office where he answered his mail and made himself available for interviews. When ABC News put out a documentary on the life of Franklin Delano Roosevelt in 1982, one of those interviewed was former Congressman Hamilton Fish, dapper in a blue suit. Fish insisted FDR would have continued running for office and would have served ten terms had he lived long enough.

Remaining active long after most men had died, much less retired, Hamilton Fish lived to celebrate his 102nd birthday in December 1990. Fish died January 18, 1991, of congestive heart failure. By the time of his death, the former congressman was known as Hamilton Fish Sr. while his son, the congressman, was known as Hamilton Fish Jr. The elder Fish’s grandson, also named Hamilton, ran for Congress unsuccessfully as a Democrat. Doubtless, it gave the former congressman great satisfaction to see his son elected in 1968 to the seat he had once held more than twenty years earlier. I can still recall in my mind a photograph of Congressman Fish aiding his father on one side, while the grandson supported his grandfather on the other. Both were dressed casually while Hamilton Fish Sr., true to his generation, wore a tie and blue blazer, steadying himself with a cane and wearing his American Legion hat. To the end of his life, Hamilton Fish continued to attend veterans’ gatherings.

© 2024 Ray Hill