The White House, following a century and a half of wars, repairs and the addition of a new third floor caused serious problems for the area reserved for the First Family. Virtually nobody thought Harry Truman would be occupying the White House in 1949 and the Republican Congress had been exceptionally generous in appropriating money for much needed repairs. The Truman restoration had its roots in the twelve years when Franklin Roosevelt had been president. FDR had been too preoccupied with the Great Depression and World War II to consider improvements to the White House. Roosevelt had made significant additions to the White House in both the West and East Wings as the President’s office and staff had grown considerably. Still, the West Wing was especially crowded and the White House did not even have a cafeteria.

A report was filed by the Army Corp of Engineers in 1941, which pointed out fire hazards, as well as structural failure in several areas of the White House. FDR’s greatest fear was fire due to his being crippled, but the President paid no attention to the report. Following the death of Franklin Roosevelt, Bess and Harry Truman moved into the White House. It was not long before Truman and his family noticed swaying floors and chandeliers moving about in an odd way. Perhaps the greatest impetus for moving along the restoration project was when a leg of Margaret Truman’s piano went right through the floor of her sitting room, which was situated above the family dining room. Upon investigation, engineers found the floor had not only rotted, but also had sunk eighteen inches over the years. The New York Times wrote, “The ceiling of the East Room…weighing seventy pounds to the square foot, was found to be sagging six inches on Oct. 26, and is now being held in place by scaffolding and supports…” Supporting bricks, which had been purchased second hand in 1880, were discovered to be disintegrating. The President’s bathtub was sinking into the floor, although the White House architect made the surprising observation the building’s “structural nerves” were impaired, but otherwise the executive residence was in “good shape.” The plumbing had become barely short of a nightmare for White House residents. The White House Historical Association noted the executive mansion was standing “by force of habit” more than anything else. After 140 years of additions and tinkering, the observation was as shrewd as it was accurate.

Truman never lost his sense of humor, but his wife Bess was somewhat more dour, especially in public. President Truman was taking a bath while Mrs. Truman entertained friends from the Daughters of the American Revolution in the Blue Room of the White House. As Truman bathed, the First Lady noticed the chandelier in the Blue Room wobbling dangerously. The President joked he very well could have landed in the midst of the Daughters of the American Revolution in his bathtub wearing nothing but his glasses. Truman said the upstairs floor “sagged and moved like a ship at sea.” It was a year later when Margaret Truman’s piano leg went through the floor.

As to the White House plumbing, John Quincy Adams was the first president to bring water that could be pumped into the White House. Unfortunately, according to the White House Historical Association, it was only used to water the president’s garden. Tennessee’s Andrew Jackson was the first chief executive to have running water inside the White House as well as the first “bathing room.” Flushing toilets were installed while Millard Fillmore was president, but it was Franklin Pierce who had the first “modern” bathroom constructed inside the White House. Some members of the Senate viewed the idea of indoor plumbing inside the White House with horror. They believed the idea of indoor bathrooms were distinctly unsanitary. Before 1850, presidents and janitors alike had to leave the White House to relieve themselves.

Another modern convenience was the telephone. The first telephone was installed in 1877 during the presidency of Rutherford B. Hayes. President Hayes was astonished the first time he used the telephone and declared Alexander Graham Bell’s invention “wonderful.” The White House number was quite easy to remember; it was 1. Nor was the White House telephone placed on the president’s desk. That did not occur until Herbert Hoover occupied the Oval Office.

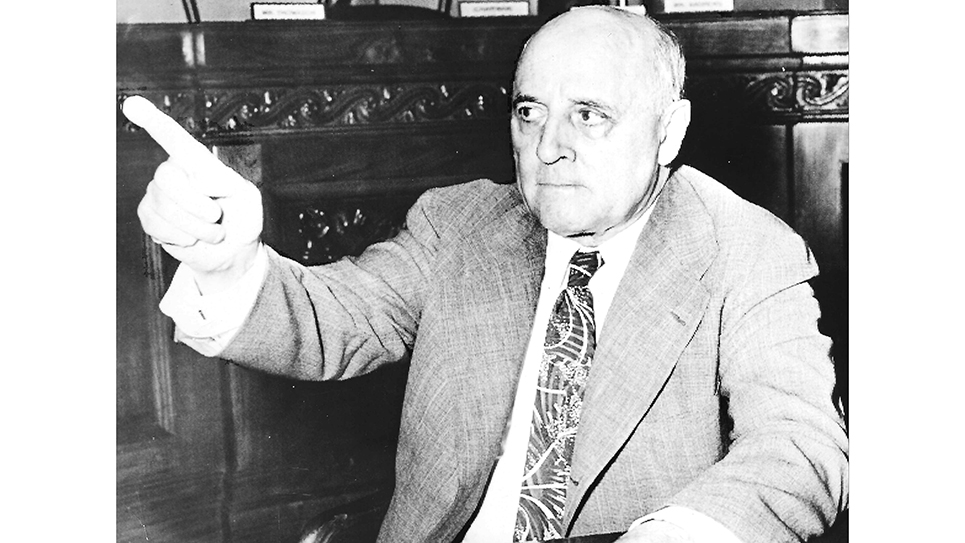

Author Robert Klara, who wrote “The Hidden White House,” extensively detailed the many serious flaws with the building. As Truman campaigned in 1948, Klara wrote a more thorough investigation of the condition of the White House gave cause for considerable alarm. The foundations for the walls supporting the upper floors of the White House were all but gone; the investigation concluded the interior of the White House was sinking into the ground and there was every reason to believe the entire structure was in imminent danger of collapse. The White House was no longer safe for the Trumans to live in, nor was it safe for the many employees who worked there. Congress responded by creating the Commission on the Renovation of the Executive Mansion, which allowed Truman to appoint two of the six members, with the Senate and the House of Representatives appointing the other four. Tennessee’s senator Kenneth D. McKellar was appointed to serve on the commission and was named chairman. The other Congressional members were Senator Edward Martin of Pennsylvania, Congressman Louis Rabaut of Michigan, and Congressman Frank Keefe of Wisconsin.

Shortly after being named to the commission, McKellar suffered second and third degree burns when he fell into a bathtub with overheated water. Senator McKellar sent his resignation to Vice President Alben W. Barkley, saying his accident made it impossible for him to serve on the commission. McKellar’s resignation was refused and after a time in the hospital, the veteran senator returned to work. Chairman of the Senate’s Appropriations Committee once again, McKellar added to the money allotted by the previous Republican Congress. The Tennessee Democrat told his colleagues on the floor of the Senate spending the public’s money had shattered his own boyhood dreams. As a boy, McKellar thought it must be wonderful to have money to spend. Senator McKellar wryly noted he had shepherded $30 billion in appropriations alone by early August of 1949. “As a boy,” McKellar said, “I thought the greatest joy on earth would be to spend money.” “I never had any,” McKellar added, “but I saw other people spending it.” McKellar sighed and concluded, “I’ve learned that spending money is a hard job if a man is conscientious – – – and God as my judge I’ve been conscientious.”

Tearing down the White House had been seriously considered, but eventually it was determined to gut the interior and leave the exterior walls standing. Senator McKellar made the announcement “after a long conference at the White House.” Instead, the White House would undergo a $5,400,000 renovation. The renovation was much more than the “facelift” described by much of the press; for most of his term in office, President Harry Truman and his family lived in the Blair House.

Congressman Frank Keefe confided it had been a difficult decision whether to raze the White House or renovate it. Keefe realized the White House was more than a building or a residence; it represented the very history of America and was an important symbol to the American people. “Gaping holes appear on the floors where the nation’s greatest men and women have tread,” Congressman Keefe said, “exposing the corrosion and decay which have taken possession of this grand old building.”

Harry Truman recognized the importance of the White House to Americans better than anybody and he had testified before Congress to urge restoration rather than demolition. “It perhaps would be more economical from a purely financial standpoint to raze the building and rebuild completely,” Truman admitted. “In doing so, however, there would be destroyed a building of tremendous historical significance in the growth of the nation.”

President Truman was photographed with the members of the commission on the White House grounds after inviting them to tour the building in June of 1949. Around the same time, Senator McKellar was at the center of a controversy involving a photograph taken by Ms. Marion Carpenter, a freelance photographer. Political columnist Tris Coffin had made the mistake of referring to Ms. Carpenter having “teased and smiled” to convince the old senator to pose for a photograph. Evidently susceptible to Ms. Carpenter’s charms, McKellar posed for a photograph and apparently liked the end result well enough to purchase large copies in quantities. “I don’t tease anybody into posing,” Marion Carpenter snapped to a reporter.

Marion Carpenter found Tris Coffin eating in the Senate cafeteria and flung a bowl of the famed bean soup in the startled columnist’s face, bellowing, “Here’s an exclusive for you!” The tall and raven-haired Marion Carpenter then stomped off. An angry Coffin said he regretted his mention of Ms. Carpenter “as favorable and factual.” Coffin’s reference to Ms. Carpenter’s method of persuasion stated she “talks her subjects into putting on makeup” for “eye-opening character studies of the greats in Congress.”

The restoration of the White House was a painstaking process, which involved storing every piece of the interior structure, including the walls, so the exterior walls could be reinforced with brand new concrete columns.

Truman, a veteran of the Senate, might have despaired at times with Senator Kenneth McKellar’s occasional displays of bad temper, but was shrewd enough to know when the Tennessean was committed to a project, he pursued it relentlessly. McKellar saw to it the White House restoration had the necessary funds and in January of 1950 celebrated his 81st birthday. As he got older, the senator was a bit touchy about the topic of his age. When reached in Washington and asked by a reporter for a comment, Senator McKellar barked, “I am happy that the Good Lord has been so kind to me to this time.” Asked whether he had any special plans to celebrate his birthday, the senator refused to comment. As the restoration was reaching completion, McKellar had to fend off Senate Republicans in the Appropriations Committee, who complained about various costs. McKellar was resting in Memphis when he was called back to Washington for “urgent” business involving the Commission on the Restoration of the Executive Mansion in November of 1951. Anticipating his seventh bid for the U. S. Senate, McKellar said, “I regret having to leave so hurriedly and hope to be able to return soon and carry on my visit in Tennessee.”

Harry Truman and his family finally moved back into the White House on March 27, 1952. The President was given a gold key to the White House in a small ceremony just at the entrance of the executive mansion. The White House was much the same as it had been before the Trumans had moved to Blair House, but 48 rooms had been expanded to 54. Both the spaces open to the public and the quarters reserved for the president’s family were restored to look like the original rooms. By February of 1952, workers sanded the floors, installed tiles and painted the walls. Soon thereafter, furniture began arriving from storage in anticipation of President Truman and his family returning to live in the White House.

Yet another innovation made its way into the White House when President Truman led a reporter on a televised tour of the executive residence, an event watched by an estimated 30 million Americans. The restoration of the White House pushed by Harry Truman was clearly the most extensive and radical in the history of the executive residence.

The changes initiated by Harry Truman remain to this day.