Idaho’s Conservative: Herman Welker

By Ray Hill

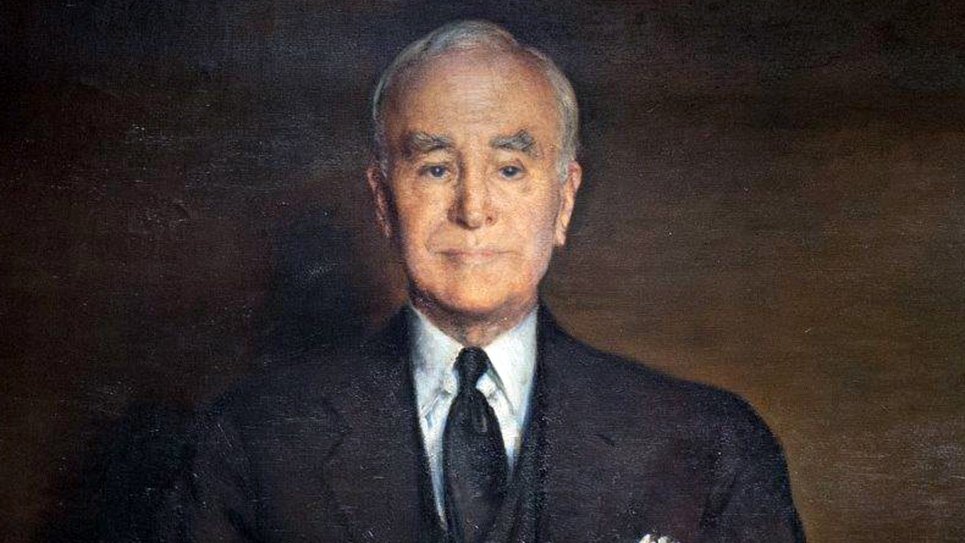

It’s been 66 years since Herman Welker died and very few outside of his native state of Idaho remember his name. Welker served a single term in the United States Senate, but during his time as a member of the world’s greatest deliberative body, he was a thorough-going conservative. Some thought Welker was too far to the right. TIME magazine, the premier news magazine of its day and read by millions of Americans each week, was published by Henry Luce, a strong internationalist Republican. TIME once described Herman Welker as belonging to the Republican Party’s “stalagmite branch.”

A man of conviction with a forceful personality, Herman Welker was also involved in one of the most sordid events in the history of the United States Senate. That involvement would mar and taint his reputation to this day.

Welker wasn’t without intelligence. While still in law school, the future senator was appointed prosecuting attorney for Washington County and was twice reelected. Herman Welker moved his wife and daughter to Los Angeles where he practiced law from 1936-1943. Welker went into the Air Corps and returned home to Idaho in 1944 and continued practicing law. Welker was elected to the Idaho Senate in 1948 and sought the GOP nomination for the United States Senate. The incumbent was Glen H. Taylor, a sometime entertainer who had beaten Senator D. Worth Clark in the 1944 primary and defeated a sitting Republican governor in the general election. Taylor had continued to feud with members of his own party, but he seriously antagonized many Idaho Democrats when he bolted his own party to accept the vice-presidential nomination of the Progressive Party with Henry A. Wallace. The Progressive Party was heavily influenced and infiltrated by Communists, a fact noted by many traditional liberals, including Eleanor Roosevelt. The Progressive Party fling caused thousands of Gem State residents to view Glen Taylor as a far-left eccentric.

Herman Welker announced for the U.S. Senate, saying he was running to “relieve Idaho of the embarrassment of Glen H. Taylor.” Welker spent most of his time in the primary ignoring his GOP competitors and instead concentrated his political fire on Glen Taylor.

While practicing law in Los Angeles, Welker became friends with crooner Bing Crosby, who was a client and proved to be a huge asset when the lawyer was running for the United States Senate in 1950. Crosby vacationed in Idaho and Welker and the singer had hunted pheasant for fifteen years together. Crosby sponsored a big dinner for his friend and joked he intended to write it off on his income taxes and make the Democrats pay for it. “This is more than just a gesture of friendship,” Bing Crosby explained. “I would not be dismayed if it were taken as an indication of my political philosophy. Some of you may think an actor has no business in politics, but our situation is so serious even a ham actor can concern himself with it.”

Senator Taylor lost to the more conservative D. Worth Clark in the Democratic primary and Welker won the general election overwhelmingly. Forty-four years old when elected, Herman Welker was off to Washington, D.C. To say Herman Welker did not make the most of his time in the U.S. Senate would be putting it mildly. Welker’s Senate service saw him repeatedly antagonize others needlessly in an institution where relationships matter very much.

Holmes Alexander, a conservative Republican-leaning national columnist summed up the faults of Welker’s Senate tenure during the 1956 campaign. Alexander’s criticism was summarized as “the senator’s absenteeism was high, prestige low among colleagues and the press corps, his office a haven for political hacks from back home, his payroll loaded with ‘do-nothing relatives’ and had ‘made a sorry spectacle of himself as a ranter … and a bully of witnesses in committee.”

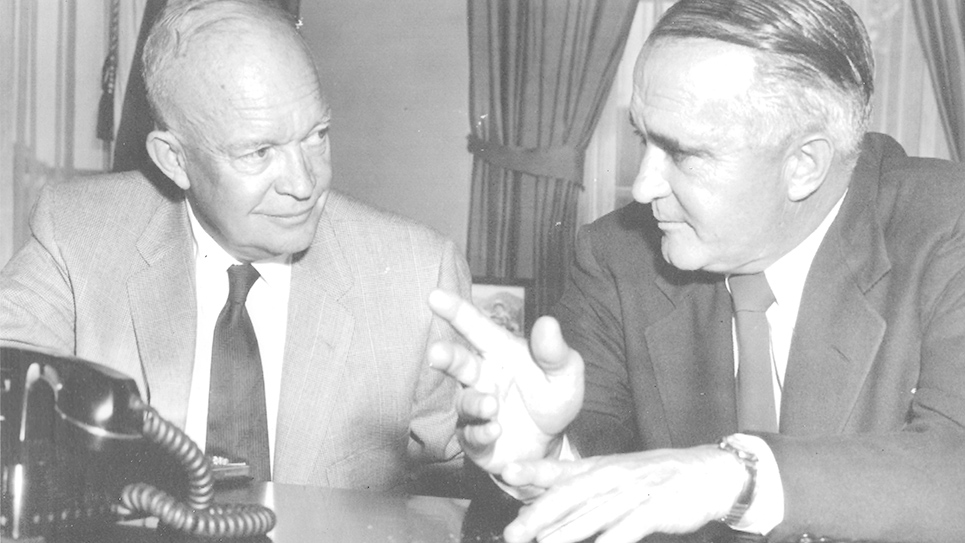

In 1954 Welker managed to cause a row when he slipped in a new federal judgeship for Idaho into a judiciary bill. Once the new judgeship was created, Herbert Brownell, President Eisenhower’s attorney general, refused to heed the pleas of Senator Welker to appoint his former campaign manager, Fred Taylor, to the office. Brownell consulted with Idaho’s senior United States senator, Henry Dworshak, who floored the attorney general when he replied he didn’t think Idaho needed yet another federal judge, nor did he want another judgeship in his state. Senator Dworshak told Brownell he would not recommend anyone. Welker in the meantime was sending not-so-subtle hints he would attempt to trifle with the Justice Department’s legislative program in the Senate if Taylor were not named to the post. Exasperated, Brownell contacted Leonard Hall, chairman of the Republican National Committee, hoping Hall could reason with Senator Dworshak. Apparently, that only succeeded in making Dworshak angry. The senator snapped his attitude would not change even if it meant the national administration would not back his reelection campaign that year. Hall, aghast, quickly tried to soothe the senator, assuring Dworshak the RNC would do all it could to reelect him. Assistant Attorney General William Rogers tried to smooth the senator’s ruffled feathers, saying of course the Eisenhower Administration was going to help him. “Yes, by holding my head under water,” Dworshak replied angrily.

Fred Taylor’s name finally went to the Senate and although Senator Dworshak offered little in the way of support, Herman Welker got his way.

1954 was also the year that Herman Welker joined with New Hampshire’s Style Bridges in attempting to leverage a personal misfortune into a political advantage. Senator Lester Hunt of Wyoming had twice been elected governor of his home state and beaten a GOP incumbent to win election to the U.S. Senate in 1948. Hunt announced he would be a candidate for reelection when his son Lester Jr., known as “Buddy,” was arrested by an undercover policeman for indecency. It was a polite way of saying Buddy Hunt had propositioned an undercover officer. Eventually, the case came to the attention of Bridges and Welker, who tried to apply pressure to keep Hunt from running for reelection. Fearing what would happen if the incident were widely exposed in Wyoming and elsewhere, worried that it would ruin his young son and perhaps shatter his wife’s emotional well-being, Lester Hunt toted a rifle poorly hidden under his overcoat into the Senate Office Building. Senator Lester Hunt shot himself at his desk and died in the hospital a few hours later. Those personally touched by the incident never really got over it. There is good reason to believe Styles Bridges was at least human enough to have suffered both shame and guilt for what was a vile episode. Bridges, once one of the most prominent of GOP senators, retained his influence, but largely confined himself to the shadows on Capitol Hill. Unfortunately, Herman Welker did not seem as affected by the incident as his colleague, although those close to the Idaho senator noted his paranoia seemed to be increasing. Worried about Communists and communism, Welker carried a gun. It is no surprise Welker is best remembered today, if at all, as one of Joe McCarthy’s chief defenders in the Senate. Welker voted against the censure resolution which broke McCarthy’s spell.

Welker’s close association with Joe McCarthy in the Senate won him the dubious nickname of “Little Joe from Idaho.” Welker’s part in the attempt to blackmail Lester Hunt into dropping his reelection bid was evidently thoroughly researched by Frank Church’s campaign staff. Compiling the, at best, distasteful and sordid facts of the case, the Church campaign high command composed a pamphlet for distribution in the state unbeknownst to Church. Once Frank Church found out about the pamphlet, he not only refused to sanction its use but, to the dismay of his staff, ordered all 50,000 leaflets be burned in a gigantic bonfire behind the campaign office. Church insisted he wanted to beat Welker on the issues.

Senator Welker’s 1956 reelection campaign was not going well. The senator, subject to period bouts of deep depression and temper tantrums, was very well financed but otherwise seemed to be lagging behind the fresh face of Frank Church, who was also an excellent speaker. Glen Taylor continued to insist he had been the victim of voter fraud by the Church campaign and in his memoirs wrote the Welker campaign gave him $35,000 (almost $400,000 today) to help wage a write-in campaign in the general election.

Rumors circulated during the 1956 campaign as Senator Welker had collapsed twice without explanation in the Capitol. Coming home to Idaho to campaign, Welker had stumbled and fallen down the stairs of an airplane. There were whispers the senator was drinking heavily.

When the Committee for an Effective Congress endorsed Frank Church, Senator Welker dismissed it as a “radical bunch of pinks and punks.” Welker’s reelection campaign tried to portray the senator as independent, a man who pulled no punches, and was a fighter for Idaho. None of the hyperbole outweighed Welker’s time in the Senate and the public image that had become fixed in the minds of thousands of Idahoans.

While President Dwight D. Eisenhower was carrying Idaho by 61,000 votes in the 1956 election, Senator Herman Welker was losing to Frank Church by 47,000 votes. A few months after his defeat, Senator Joe McCarthy charged the “Eisenhower for President gang in Idaho” had been against Welker’s reelection to the Senate. McCarthy said the president had purged Senator Welker from office. McCarthy dismissed the letter written by Eisenhower urging the people of Idaho to return Welker to the U.S. Senate. McCarthy snarled it was merely “some milk and water letter.”

Unlike many contestants for political office, Herman Welker publicly gave vent to the “hurt” he felt after having been “so thoroughly beaten in my bid for reelection.”

“Of course it hurts to have your neighbors give you a ‘no confidence’ vote at the polls. In fact, I have been the loser in all kinds of contests, but nothing equals that shock, that chagrin and embarrassment that comes the morning after election when you are told you are through … that your services to your state and nation are no longer needed. You can hardly face your family, let alone your friends … ” Welker mused, “Maybe I went overboard on patting myself on the back. It is easy for a public servant to imagine himself in being a great man.”

Following his loss in the general election and his leaving office on January 3, 1957, Herman Welker left Washington, D.C., to return to Boise where he opened a law office. Welker traveled to Chicago to speak to the Abraham Lincoln National Republican Club where he made his public remarks about his defeat.

Back home in Idaho, Welker was attempting to paint around the roof of his house when he fell off the ladder twice and gave up. There was good reason why his balance was bad, although it was unknown at the time.

It was not long before Herman Welker was seriously ailing. Welker was admitted as a patient to the National Institute of Health on October 17, 1957, where he underwent surgery to relieve pressure on his brain. Doctors discovered the former senator was suffering from a brain tumor. By October 23, the former senator was on the critical list. Welker underwent a second operation on October 28 in an attempt to remove the brain tumor. By October 31, 1957, Herman Welker was dead.

Most of the eulogies from Welker’s political contemporaries were carefully worded. Senator Dworshak said, “The tragic passing of Herman Welker removes one of the most colorful figures in Idaho political history.” His recent opponent, Frank Church, was gracious while acknowledging they had been “political adversaries,” stressed Welker had been kind in their personal dealings.

Welker’s earthly remains were borne to his gravesite in Arlington National Cemetery by a horse-drawn caisson. Reverend Frederick Brown Harris, chaplain of the United States Senate, preached at the late former senator’s funeral.

© 2024 Ray Hill