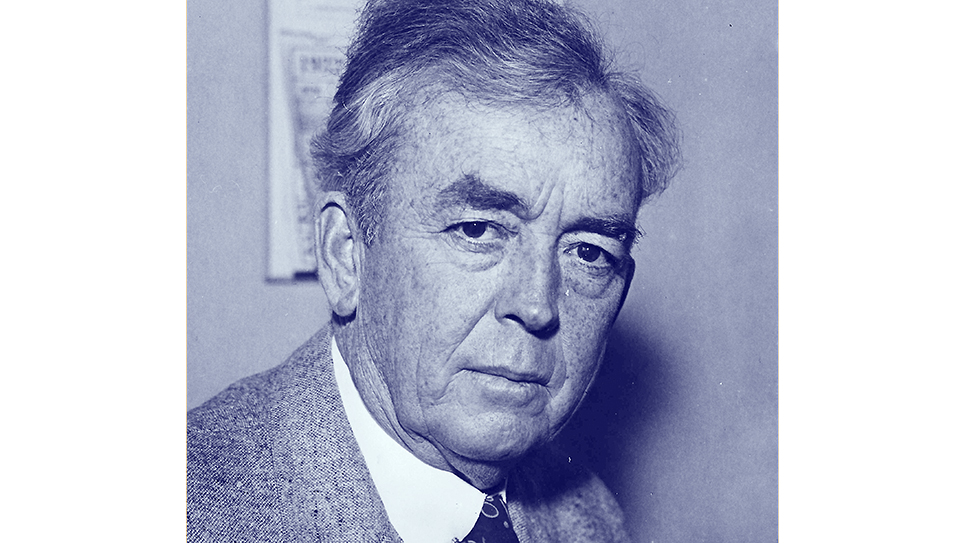

John E. Rankin of Mississippi

By Ray Hill

It is a very rare thing when a human being has absolutely no redeeming feature. There have been instances where someone, usually a psychopath, doesn’t seem to have one good quality. The People’s House – – – the U.S. House of Representatives – – – is a reflection of the attitude of those who send men and women to Congress. John Elliott Rankin was a member of Congress for 32 years and he exemplified the best and the worst of the prevailing attitudes of his time in his home state of Mississippi. The Magnolia State was a one-party state in Rankin’s day, still smarting from the losses inflicted by the bloody Civil War and the hated carpetbaggers who came to govern the state during Reconstruction. To most Mississippians, there were few things worse than Republicans.

John E. Rankin was a slight man with a mop of white hair who was early to rise and made a habit of walking to his office in Washington daily from his apartment in the nearby Methodist Building. Rankin liked to brag he had accomplished half a day’s work before most of his colleagues had arrived in their own offices. If Rankin was a man of small stature, everything else about him – – – his personality, tenaciousness, booming voice and savage oratory – – – were all outsized. Congressman John Rankin was something of an eccentric. His dislike of the smell of paint was so pronounced it is probable his suite of offices in the House Office Building likely hadn’t been painted since he had moved in to occupy them. When painters were attempting to paint doorways near his own office, the Mississippi congressman forbade it. The job had to wait until he left Washington to return to Mississippi. It was rare for Rankin to leave Washington, D.C., as he insisted on remaining at the Capitol during most of the congressional holidays, recesses and the like.

Despite his diminutive size, John E. Rankin needed no magnification of his voice to reach the upper rafters of any meeting. According to one contemporary observer, Rankin “spoke in a rather high-pitched piercing voice” from which venom could easily drip, especially when the Mississippian was agitated. It was not difficult to agitate John Elliott Rankin.

Even during his own time, John Rankin was one of the most controversial members of Congress. Far from being accepted by most citizens, Rankin’s blatant racism horrified many, including some fellow Southerners, and was roundly denounced in many quarters.

Rankin always liked to be personally present on the House floor during the opening and closing session of the House “because that’s when the skullduggery is done” the congressman explained to a visiting reporter.

Throughout his time in the House, Rankin lectured his colleagues on any number of topics, most of which they could have done without. John E. Rankin spoke frequently about the blessings of the Tennessee Valley Authority, which he had sponsored in the House of Representatives, as well as the Rural Electrification Administration which brought light to tens of thousands of homes in his congressional district and throughout the South. As in the case of the TVA, John Rankin had been the House sponsor of the original legislation to create the REA. A veteran of the First World War, John E. Rankin was the long-time chairman of the House Committee on Veterans’ Affairs and there was no bigger advocate for veterans in Congress than the Mississippian. Rankin worked, along with Edith Nourse Rogers of Massachusetts, to shape the legislation that became the G.I. Bill of Rights approved by Congress.

The Mississippi congressman liked to hold the House floor and decry Southern freight rates, which he insisted were unfair to the people of the South. Rankin was an outspoken and powerful advocate for the creation of the Tennesse-Tombigbee Waterway, a project that did not come to fruition until well after the congressman’s death. John Rankin’s other topics of hatred was scalding and, in some cases, loathsome, especially when it came to racial matters. For those who insist we live in a terribly racist, white-supremacist society today, the oratory of Congressman John E. Rankin would cause them to likely faint dead away. The fiery little Democrat from Mississippi really was a full-blown white supremacist and made no apologies for it; quite to the contrary, he was proud of it.

Rankin was virulently anti-Communist at a time when virtually every member of Congress realized the threat of communism to the United States. John Rankin was responsible for creating the House Committee on Un-American Activities.

Members of the House Press Gallery grew amused by the almost daily lengthy statements and pronouncements on issues flowing out of Congressman John Rankin’s office. The Mississippian was promptly sarcastically dubbed “Silent John” for the torrent of printed words pouring into the press gallery. Rankin’s news bulletins were released to the press and printed on slick yellow paper, notifying the newsmen Congressman Rankin was opining on yet another issue or topic. Rankin was so regular with his nearly daily bulletins the newspaper writers wondered what had happened when the congressman had not sent any press releases for three days. On the fourth day, a statement, written on the familiar yellow paper arrived in the press gallery. Most of the reporters began their story by writing, “Breaking his long silence Rep. John Rankin said today … ”

When Speaker of the House Henry Rainey died suddenly, John Rankin jumped into the race to succeed him but was never taken seriously by fellow Democrats. Nor did Rankin’s ambitions stop there. When race-baiting Senator Theodore Bilbo died, Rankin entered the special election to fill the vacancy. Rankin boldly bragged he would “out-Bilbo Bilbo.” Although he campaigned hard, times were already changing in Mississippi. Neither of the two strongest candidates, John Stennis and Congressman William Colmer, made white supremacy an issue. John Rankin got a thorough beating at the polls.

Angry that his fellow House Democrats had removed him from the House Un-American Activities Committee, Rankin purposely sponsored a bill that would have provided overly generous pensions to veterans and their widows. The cost of the legislation was deliberately high as Rankin calculated no congressman wished to appear to be unfriendly to veterans or their widows and orphans. According to some estimates, the Rankin Bill would cost more than the country had spent on veterans since the Revolutionary War. Seven members of the House Veterans Affairs Committee stomped out of the hearing room in protest after Rankin managed to sledgehammer the bill through. As to those congressmen who protested the high and questionable cost of the legislation, Rankin serenely replied, “If we can spend untold billions of dollars on other countries, feeding and clothing every lazy lout from Tokyo to Timbuktu – – – then we can take care of our aged veterans when they are unable to care for themselves.” Rankin devilishly turned a newly approved House Rule to his own advantage. That rule had been aimed at Rankin by the leadership of the House and permitted the chairman of committee to bring a bill out after the Rules Committee had pigeon-holed it for 21 days. In short, Rankin was gleefully forcing every member of the House to vote on the record for or against his bill. With the confidence of a fox entering the hen house, John Rankin “rolled his stupendous veterans’ pork barrel onto the floor of the House and defied the quaking Congressmen to throw it out.”

Leadership determined the only way to outmaneuver the wily old Mississippian was by allowing veterans in the House to take the lead in beating the bill. Twice the bill was defeated in standing and teller votes, which were not recorded. John Rankin demanded a roll call vote and watched with satisfaction as the House of Representatives did precisely what he believed they would do: keep his bill alive. “A revival of righteousness,” Rankin exulted.

The next day the debate was led by Congressman Charles Potter of Michigan, a veteran who had lost both legs in the Second World War. Aided by crutches, the congressman walked to the well of the House on artificial legs. “I hate to see the veterans of this country used as political pawns in this great Washington game of cheat,” Potter told his colleagues. Congressmen began attaching amendments to the Rankin Bill to make it unpalatable to almost everyone.

By the third day of intense debate, Congressman Olin “Tiger” Teague of Texas moved to kill the Rankin Bill outright. Teague was also a veteran of the Second World War, and his valor was unquestionable, having been wounded three times in combat. Knowing how close the vote was likely to be, there was complete silence in the House Chamber. In fact, TIME magazine noted it was so quiet the click of the Clerk’s “mechanical hand counter was audible in the galleries.” The Clerk announced the final vote, 208 to 207. By a single vote, the House had killed the shrewd John Rankin’s bill.

To remove John Rankin from Congress, the Mississippi legislature, facing the loss of a congressional seat, put Rankin in the same district as his colleague Tom Abernethy. The aging congressman campaigned gamely and hard but lost to Congressman Abernethy by a wide margin. Abernethy even beat Rankin inside his native county.

Vito Marcantonio, a congressman from New York, according to liberal news columnist Drew Pearson, “liked practically everything with a Russian flavor,” which was a polite way of saying the New Yorker was the closest thing to a Communist in the U.S. House of Representatives. Rankin, Pearson wrote, made a career out of being “agin’ Negroes, Catholics, Liberals and Northerners.” Both Rankin and Vito Marcantonio had lost their seats in the 1952 election. Pearson wrote a column stating while the two publicly hated one another, privately each personally liked the other. According to Drew Pearson, both realized the usefulness of the other when campaigning for reelection inside their respective districts.

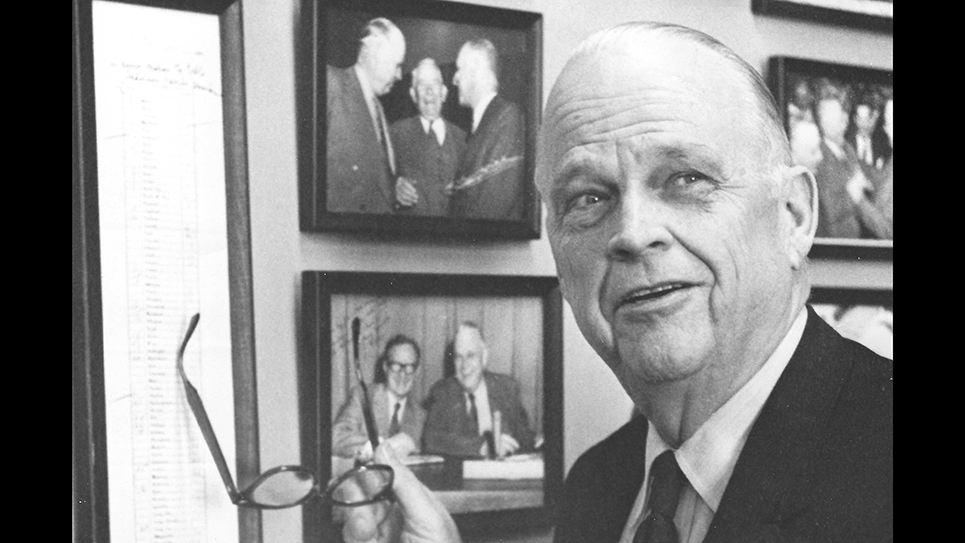

Following his defeat in the Democratic primary in 1952, Rankin had months to acclimate himself to private life and the idea of beginning anew at the age of 72. Ignoring the House rules, which stated he should have vacated his suite of rooms, the congressman was found by an errant newspaperman while rattling around his office. Noting he was something of a “lonely figure,” Gordon Brown recalled Rankin had occupied Suite 358 in the Cannon House Office Building for the last 22 years. That day, Rankin’s nameplate outside the door to his offices was due to come down after 32 years in the House of Representatives. Asked about his future plans, the congressman replied, “Well, down in Tupelo (Miss) I own 180 acres right in the city limits and I think I’ll do some real estate business for a while.” After thinking for a few moments, Rankin said his hometown of Tupelo was “booming” due to gas and oil strikes in the area. “I may get into that,” Rankin added hopefully.

Like many an aging incumbent forced to retire involuntarily, John Rankin said it was a “relief” to leave Congress. “There’s been terrific pressure on me, heavy responsibilities, constant pulling and tugging,” Rankin told Gordon Brown. “Yes, it will be a relief to get away from it.”

As he prepared to return home to Tupelo, John Rankin offered some advice to the new Congress. “Concentrate on cleaning out the subversives, protecting our own country and developing our own resources,” Rankin said. The Mississippi congressman counseled lawmakers to urge the United States to return to a policy of “no entangling alliances.”

Once out of Congress, John E. Rankin’s health began to fail. It was as if denied the public forum he had enjoyed for so long, the life force inside him seemed to seep out and evaporate. For the last three years of his life, John E. Rankin was confined to his home in Tupelo. The former congressman died in 1960; he was 78 years old.

© 2024 Ray Hill