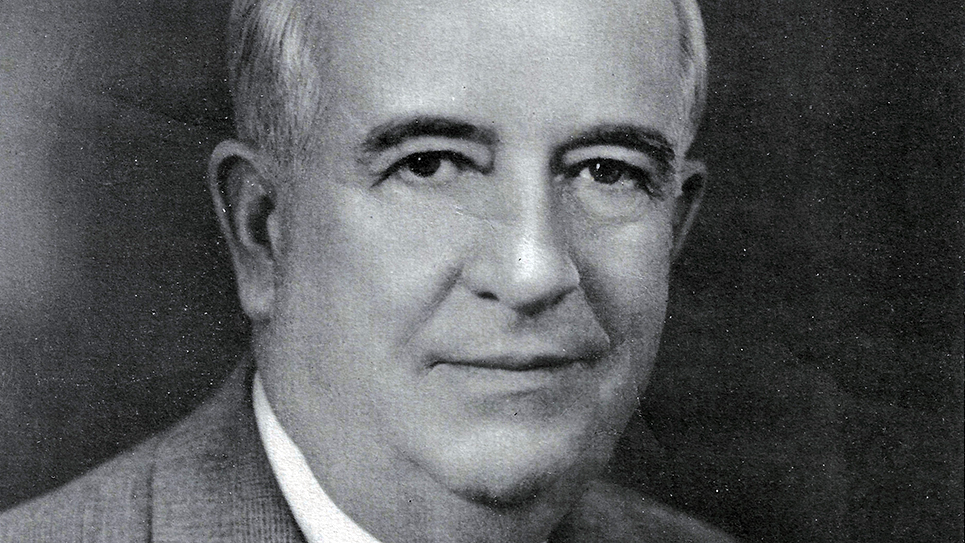

John J. Dempsey of New Mexico

Each state in the union has its own set of variables and peculiarities, all of which affect its politics. The political history of New Mexico is a mixed bag with the deeply embedded Spanish culture and the “Anglo” politicians. There have been a number of individuals who have left their political mark on the Land of Enchantment, including Dennis Chavez, who served in the House of Representatives and the United States Senate from 1931 until his death in 1962. A contemporary of Chavez and his frequent rival, John Joseph “Jack” Dempsey enjoyed a lengthy career in the fractious and hard-fought politics of New Mexico. At one time a water boy on a railroad, Dempsey made enough money in the oil business to consider an early retirement in New Mexico. Dempsey’s affiliation with Brooklyn Rapid Transit, Continental Oil & Asphalt, and the U.S. Asphalt companies had left Dempsey independently wealthy. Rather than retire, John Dempsey became preoccupied with politics, which eventually caused him to rise to become governor of New Mexico.

One of the best resources for portraits in miniature of prominent men and women of the day, TIME magazine noted “red-faced, white-haired” John J. Dempsey was one “of the most popular men in Washington.” Noted for his penchant for hard work, TIME stated Dempsey had achieved a record by passing 99 of his own bills in his first six years in the House of Representatives.

Most people acquainted with politics are familiar with the Hatch Act, named for its sponsor, Senator Carl A. Hatch of New Mexico. One reason the Hatch Act was successfully passed initially was because many senators never imagined it would pass the House. That was before Jack Dempsey got behind it, telling friends, “I’m going to pass that bill.”

The Roosevelt Administration was not pushing the Hatch Bill and most of the leaders in the House were against it. Hatton Sumners, the crusty and powerful chair of the House Judiciary Committee, was perhaps the most formidable opponent the Hatch Act faced in the House of Representatives. When the Judiciary Committee held a secret ballot and announced the vote was 14 to 10 to table the Hatch Act, Congressman Dempsey caused a major ruckus when he declared at least thirteen committee members had told him they had voted for the bill. Dempsey then started a petition to force the Hatch Act out of the House Judiciary Committee and for a time, congressmen avoided the New Mexican like the plague. Not the least bit deterred, Dempsey relentlessly pursued members of the House Judiciary Committee and “wheedled, cajoled and bullied them for almost a month.” The Hatch Act was passed by the House Judiciary Committee 16-8.

The fight was not yet won and Dempsey appeared before the House Rules Committee where he made a personal appeal to the members. “I’m a member of this committee and I want you men to give me this rule just because it’s me.”

“Why is it a worse crime for the poor fellow who is out in the open somewhere, drawing $100 or $150 a month, to engage in political campaigns any more than a Cabinet officer?” Claude V. Parsons of Illinois demanded to know.

“He engages in political campaigns in most instances as he is directed, as he is forced to engage in it,” Dempsey shot back. “That is the difference!”

That worked and the Hatch Act moved to a vote of the full House. When Hatton Sumners made a final sizzling attack on the Hatch Bill, Jack Dempsey fought the powerful committee chair and won, 243-122.

When the bill won by Jack Dempsey made it over to the Senate, Vice President Garner was ready to gavel it through when Roosevelt administration stalwart Sherman “Shay” Minton (a future justice of the U.S. Supreme Court) moved to send the bill to conference.

That caused Senator Hatch to jump to his feet in defense of his own bill. “Let nobody be deceived… by the issue,” Hatch thundered. “A vote to send it back to conference is… a vote to send the bill to the graveyard. Let there be no hiding behind good intentions… and then send it back to conference where we know it will die!”

Senator Minton’s surprise by Hatch’s vehemence was visibly etched upon his face and he retreated. “I wanted to take a look at the bill,” he muttered. “I have no dagger up my sleeve for his beloved bill. I have no intention to knife my friend in the back. So far as I am concerned, the Senator may have his bill, and God bless him.”

It was on the heels of his victory in the House of Representatives that Jack Dempsey made the announcement he would challenge one of the most notorious foes of the Hatch Act in the Senate, Dennis Chavez, in the 1940 Democratic primary. Chavez’s family was thoroughly political and had been involved in a WPA scandal, which necessitated a trial and ended in an acquittal. That had been one of the reasons why Hatch had sponsored the legislation in the first place, yet it was John J. Dempsey who had worked so hard for its passage in the House of Representatives.

The political dynamic of a small state is obviously quite different than that of a larger state. While many Western states occupy a large land mass, they had smaller populations, which meant politics was frequently only successfully practiced through hard work and personal contact. A small state’s representation in Congress oftentimes mattered very much to the people of that particular state. Much like Southerners, Westerners frequently recognized the value of electing someone to Congress and keeping him there to accrue influence and seniority. Perhaps the best example of that is Carl Hayden of Arizona, who served either in the House of Representatives or the United States Senate from the time Arizona achieved statehood in 1912 until his retirement in 1969. Hayden was adamantly against the notion of voting against cloture, the legislative means of closing off debate. Senator Hayden believed it helped to protect the rights of the minority and smaller states.

John J. Dempsey was one of those who relocated to the West and made his home and career there. For decades, Dempsey prospered in the rough and tumble of New Mexico politics.

Born in White Haven, Pennsylvania, Dempsey found his way to New Mexico via Oklahoma, where he had gone to engage in the oil business. By 1920, John J. Dempsey had moved to Santa Fe, New Mexico where he worked as an independent oilman and eventually became the president of an asphalt company. Evidently, Dempsey’s first attraction to Santa Fe had occurred while vacationing. He later built a beautiful home in the hills overlooking the city.

Like so many other Democrats, Dempsey rose on the tide of Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal. After having served as a trustee of the University of New Mexico, Dempsey was named as the state director for the National Recovery Administration, a New Deal agency. In rapid succession, John Dempsey became the head of the Federal Housing Administration for New Mexico and the National Emergency Council. In 1934, Congressman Dennis Chavez challenged Republican U.S. Senator Bronson Cutting for the Senate.

The Cutting-Chavez race was especially hard fought and the election was contested with the senator having apparently been reelected, however, Cutting was killed in a plane crash coming back to Washington, D.C., from having gathered evidence supporting his case. Chavez was appointed to the vacancy, a fact which deeply appalled several progressive Republicans including Harold L. Ickes, Roosevelt’s irascible Secretary of the Interior. Dempsey had won the Democratic nomination for New Mexico’s lone seat in the House of Representatives. Dempsey was reelected in 1936 and 1938 before he announced his candidacy against Senator Chavez inside the primary in 1940. Chavez only narrowly beat back Dempsey’s challenge, winning by roughly 2500 votes. Dempsey was named a member of the U. S. Maritime Commission by President Roosevelt before becoming an Assistant Secretary of the Interior under Ickes. Dempsey only served at the Interior Department for approximately a year before he resigned and returned to New Mexico where he launched a campaign for the governorship. John Dempsey won the Democratic primary easily and a decisive victory in the general election against the Republican candidate.

Dempsey was reelected governor in 1944 and almost immediately it became clear he had his eyes on the Senate seat occupied by Dennis Chavez. Despite a ferocious primary, Senator Chavez won by a bigger majority, although he only barely beat Republican Patrick J. Hurley in the general election. When Senator Carl A. Hatch suddenly announced he was retiring to accept an appointment to a federal judgeship, former Governor John J. Dempsey quickly jumped into the race for the Democratic nomination for the United States Senate in 1948. Dempsey didn’t remain the front runner for long as Secretary of Agriculture Clinton P. Anderson resigned from President Truman’s Cabinet to come home and campaign for the Senate. A former congressman, Anderson easily won the senatorial nomination. Following his loss in the 1948 primary, John J. Dempsey finally appeared to give up his dream of representing New Mexico in the U.S. Senate. When former Governor and incumbent Congressman John E. Miles opted to return and retake the governor’s chair in 1950, the 71-year-old Dempsey jumped into the race for one of New Mexico’s seats in the House of Representatives. Dempsey’s familiarity with the state and name recognition helped him to run first in the primary. For the rest of his life, John J. Dempsey remained in Congress from New Mexico.

Despite his age, there was little doubt Dempsey would continue running, especially after New Mexico lost its other congressman at-large, Antonio Fernandez. Fernandez had suffered a serious stroke just before the general election in 1956. It was quite clear from reports published by the Albuquerque Journal that Congressman Fernandez was in critical condition. Although reelected, Antonio Fernandez never knew it. He remained in a coma until his death on November 7, 1956. With the passing of Congressman Antonio Fernandez, New Mexico lost valuable seniority and know-how that could not be replaced. That made John Dempsey’s own seniority even more important in the House, but time stands still for no man.

In 1958, the 78-year-old congressman showed no signs of slowing down, much less retiring. Dempsey filed for reelection to the House and was unopposed in the Democratic primary. At the end of February, Dempsey became ill and went to George Washington University Hospital in Washington, D.C. The veteran congressman was diagnosed as suffering from a “virus infection,” which was evidently serious enough to require blood transfusions and time under an oxygen tent. The aging congressman’s prognosis slid from serious to critical in a matter of days and his two daughters flew from Santa Fe to Washington, D.C. Dempsey had apparently disregarded his doctor’s instructions to remain in bed, but instead had gone to the Capitol where he had worked on an amendment to the construction of the Navaho Dam in New Mexico. According to one of Dempsey’s aides, the congressman had gone to bed that same night and his condition had become progressively worse. Whatever the infection, it was affecting the congressman’s intestines. According to Mrs. Cecilia Norris, one of the congressman’s secretaries, Dempsey was suffering from uremia.

Jack Dempsey died on March 12, 1958.

It took a Democrat to stand up to what amounted to the functioning of the New Deal political machine as explained by TIME magazine, “the army of U. S. marshals, district attorneys, WPA officers and underlings, customs collectors, inspectors, etc. etc., who worked for him so zealously in 1936 and again last year in the Purge-that-failed.” The purge was of course FDR’s effort to beat those senators who had opposed his efforts to pack the U.S. Supreme Court.

History is made by men like John J. Dempsey.

© 2023 Ray Hill