Clifford Davis had first been selected by E. H. Crump, the undisputed political boss of Shelby County, to go to Congress in a 1940 special election. Davis had remained in Congress since that time and his congressional career had likely been saved when he was shot on the floor of the House by Puerto Rican nationalists in 1954. Crump had reputedly been considering replacing Clifford Davis, but the Memphis Boss was ailing and died that fall. Even Crump had realized Davis had enjoyed a wave of sympathy and support from voters after having been wounded in the attack on the House of Representatives. The passing of E. H. Crump had also significantly changed the political landscape in Memphis and Shelby County. Crump had groomed no successor and the machine he had so meticulously built began to wobble and fall apart. Within a few years, most of the machine office holders had died, retired or been swept out. Clifford Davis was the last significant remnant of the old Crump machine to hold office in 1961.

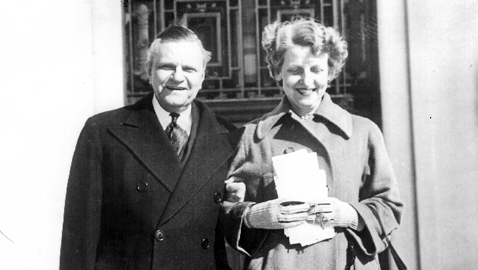

Tennessee was also continuing to evolve; the Volunteer State had gone Republican in the last three presidential elections, voting twice for Dwight D. Eisenhower (despite Senator Estes Kefauver being on the Democratic ticket in 1956) and once for Richard Nixon. While many Tennessee Democrats admired the young president, support for John F. Kennedy was not universal. There was increasing tensions between conservative Democrats and those who strongly supported the young president. Clifford Davis was viewed by many of those same young Democrats as a Jurassic relic of a time long since past. Cliff Davis certainly was not a part of the age of Camelot at the court of John F. Kennedy. Ross Pritchard, a young political science professor who had dabbled in practical politics, was seen as more representative of Tennessee’s new Democrats. Another sign that Clifford Davis was aging and vulnerable was the prospective candidacy for Congress by state senator Lewis Taliaferro. Yet there was no sign Cliff Davis intended to retire. Davis enjoyed Congress and his wife, Carrie, loved the social life in Washington, D. C. Carrie Davis was constantly busy with some social chore or another and was very well liked by most of official Washington. Early in 1962 Carrie Davis had been praised by Ladybird Johnson, wife of the vice president. “She combines the wisdom of Dolly Madison, the warmth of Rachel Jackson and the energy of Eleanor Roosevelt,” Mrs. Johnson said of Carrie Davis during a “surprise luncheon” comprised of some 500 women in Washington to honor the congressman’s wife. “She is a sturdy oak with magnolia blossoms,” Mrs. Johnson enthused. Carrie Davis was one of the 1,350 Democratic women in “beflowered spring hats and chic ensembles” for a luncheon sponsored by the Women’s National Democratic Club in April of 1962.

Congressman Davis also liked the perks of Congress, which included a trip to Paris to attend a meeting of the NATO parliamentarians in November of 1961. Cliff Davis was hardly the only Tennessee congressman flitting about the globe. Congressman Carlton Loser of Nashville had visited Switzerland, Italy, England and France that same year as a “one-man committee” to ascertain just how European legislative bodies might continue to function following a nuclear attack. Congressman James B. Frazier of Chattanooga had gone to Brussels as part of the inter-parliamentary union and went on to Denmark and France. Both Frazier and Loser would be defeated inside the Democratic primary in 1962.

Ross Pritchard, after having taken the temperature of the political waters, announced he was running for Congress on May 17, 1962. A former football star, the thirty-seven year old Pritchard had successfully managed Henry Loeb’s campaign for mayor of Memphis. Loeb also just happened to be Pritchard’s brother-in-law. Resigning his post at Southwestern university, Pritchard declared, “From Memphis and Shelby County we are called upon to send the best representative we can find, yet year after year we respond with a congressman of low performance and mediocre achievement.”

Lewis Taliaferro had already qualified to run for Congress and Cliff Davis made his own announcement he was a candidate for reelection at the end of May. The congressman underscored his opposition to much of the Kennedy White House when he opposed the administration’s farm bill, although he was hardly alone in opposing it. Congressmen Howard Baker, Louise Reece (who had succeeded her late husband), Tom Murray, James B. Frazier, and “Fats” Everett all said they were voting against it. Everett, an assistant Democratic whip in the House, represented a rural West Tennessee district and said, “The farmers in my district are opposed to it.” Everett readily admitted, “The administration has put all kinds of pressure on me but I told them I just can’t go. I’m not going to play Russian roulette with my constituents. I might miss but I could get killed.” Only Congressmen Ross Bass and Joe L. Evins announced support for the Kennedy farm bill. The opposition of many of Tennessee’s House delegation helped beat the farm bill 215 – 205, killing it for that session of Congress. Moving to recommit the legislation, only Congressmen James B. Frazier, Ross Bass and Joe L. Evins voted with the administration.

Cliff Davis was taking his opposition seriously and the congressman was absent from the House during two weeks in July when he deemed it wiser to remain inside his district and campaign than stay in Washington. Clearly, Cliff Davis’ decision to campaign hard for reelection made a difference, as he handily defeated both Ross Pritchard and Lewis Taliaferro. Davis won more than 52,000 votes with Ross Pritchard trailing a distant second with just over 32,000 votes. Taliaferro ran third with 21,000 votes; still, the combined votes of both opponents was slightly more than Cliff Davis’s total. Davis was basking in a decisive win over two serious challengers, his first real contest since having been elected to Congress in 1940. Both opponents had been highly critical of the congressman’s record, accusing him of absenteeism and generally being an ineffective representative for his district. Congressman Davis was rightly flushed with a handsome victory. “I am simply delighted,” Clifford Davis crowed.

Davis and his wife had a scare while returning to Washington, D. C. On board an American Airlines turboprop plane, the sixty-five passengers and five crewmembers were seriously frightened when the airliner careened off the runway and crashed during a thunderstorm in Knoxville. Evidently not everyone on board was scared. Seven-year-old Curtis Newman, when asked if he had been frightened, replied, “NAAW, I wasn’t scared. But I got my new tennis shoes wet.” Arkansas Congressman Dale Alford was also on the flight and was sitting by Carrie Davis during the crash. Alford kept telling Mrs. Davis to “keep calm.” “I am calm,” Mrs. Davis replied. “You’re too calm,” Alford retorted.

The passengers had to descend eight feet to disembark from the plane. “There wasn’t any grass growing under anybody’s feet,” Carrie Davis observed. Lewis T. Barringer, a wealthy cotton broker from Memphis, who was traveling with Congressman and Mrs. Davis, noted the “smell of oily smoke” coming from the plane’s engine. “After we tanked, everybody started to look for an opening,” Barringer said.

Clifford Davis’ weakness was revealed in the 1962 general election when fifty-three year old Republican businessman Bob James came within 1223 votes of upsetting the incumbent congressman. It was a sign of a growing GOP in Tennessee, as was the election of William E. Brock as congressman from the Third District after incumbent James B. Frazier, Jr. had been defeated in the Democratic primary. The closeness of the 1962 election guaranteed Bob James would once again challenge Clifford Davis two years later. It also revealed the fundamental political weakness of Clifford Davis to potential Democratic challengers and by February of 1964 local attorney George Grider was already making the rounds as a candidate for Congress. Grider made his announcement official on April 12, 1964 that he would run against Davis inside the Democratic primary. George Grider had political experience, having managed the campaign of popular former Memphis mayor Edmund Orgill, as well as having been elected to the Shelby County Court in 1959.

Cliff Davis was unable to retire gracefully and insisted upon seeking reelection and found the fifty-one year old Grider a formidable challenger, although most gave the congressman the advantage in the primary. On Election Night Davis was leading Grider, albeit narrowly. The Saturday following the primary election, with 184 of 188 precincts in the Ninth Congressional district, George W. Grider was running ahead of Congressman Davis with 43,401 votes to 35,543 votes for the incumbent. Clifford Davis’ long career in Congress was over. Davis remained a loyal Democrat despite losing the primary election. Congressman Davis praised President Lyndon Johnson’s selection of Senator Hubert Humphrey as the vice presidential candidate. “I think he would be a credit to the office and is a fine selection,” Clifford Davis said. “I will do all I can to help the ticket from top to bottom.”

Bob James was once again running hard in the general election, but unlike Clifford Davis, George Grider had no trouble winning the fall election. Republicans had believed they would face Congressman Clifford Davis on the November ballot and had not anticipated Grider winning the primary. George Grider outdistanced James by more than 11,000 votes in November. Yet Clifford Davis’s defeat may have had greater implications for Democrats than they might have imagined. Many of the old Crump supporters drifted into the Republican Party. Memphis businessman Dan Kuykendall had run for the United States Senate against Albert Gore in 1964 and had won a very respectable 46% of the vote. In 1966 Kuykendall ran for Congress against George Grider and won. Kuykendall would remain in the House of Representatives until his own defeat in 1974 by Harold Ford.

At the end of Clifford Davis’ career in Congress, his wife Carrie was reportedly being considered for a post in the Johnson administration. Carrie Davis was a very close friend of Ladybird Johnson and while Congressman Davis might very well have obtained a federal appointment for himself, he did not want one. Davis was eligible for a $15,000 (the equivalent of more than $114,000 today) annual pension, which he could not collect if he were appointed to another federal office. Congressman Clifford Davis announced he intended to open a “public relations” office in Washington, D. C. and “represent private interests” in the Capitol. The sixty-five year old congressman would spend the rest of his professional life as a Washington lobbyist. As he prepared to leave office, Clifford Davis put his wife on his Congressional payroll until his term ended January 3, 1965. Davis paid Carrie a very generous $1,398.91 per month following his defeat in the August Democratic primary.

Little more was heard of Congressman Clifford Davis, at least in Tennessee. The former congressman maintained his home in Washington and lobbied for his clients while Carrie remained active in social affairs. Carrie lead the guests of honor in a procession during a Congressional Club breakfast honoring her friend, First Lady Ladybird Johnson.

Carrie and Clifford Davis continued to live outside the bright lights of the halls of Congress in Washington, D. C. in comfortable semi-retirement. On June 8, 1970, the seventy-two year old former congressman suffered a heart attack at his home in Washington and died. Survived by his widow and three children, Cliff Davis’ body was brought home to Memphis for burial.

Today, little is remembered about Clifford Davos save for having been wounded during the attack on the House of Representatives by Puerto Rican nationalists and that he had been the last vestige of the old Crump machine in office.