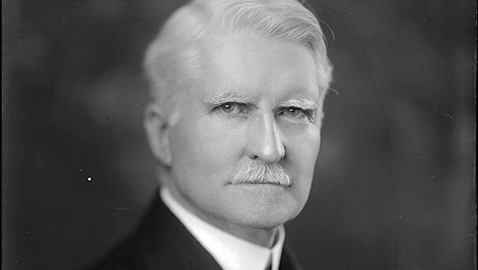

Lawrence D. Tyson was a soldier, business titan, lawyer, owner of the Knoxville Sentinel, and United States senator from Tennessee. Tyson’s only previous political experience had been one term in the Tennessee House of Representatives where he had been promptly elected Speaker. Tyson’s business interests included textile mills and coal concerns. L. D. Tyson had married well; his wife, Bettie, was the daughter of Charles McGhee, the president of a railroad. Still, success and wealth affords one no protection from the vicissitudes of life. The Tyson’s only son, Charles McGhee, had been a Navy aviator and was lost over the North Sea during World War I. It took General Tyson quite some time to locate his son’s body and he accompanied it home to Tennessee for burial.

Tyson’s beginning in life had been relatively modest, despite the fact he had been born on his father’s plantation in Greenville, North Carolina. Still, the Tyson family managed better than many of their contemporaries. The future senator was clerking in a store when he sought an appointment to West Point. Tyson knew the value of a dollar; his family was left poor after the Civil War and following his appointment to the military academy, he had to live off his army allowance. L. D. Tyson was so industrious he managed to have enough left over to buy all his required uniforms, swords, and side arms with $200 to spare. That was a handsome sum at the time, which he took with him to his post in Arizona where he fought the Apaches. Tyson took part in the military campaign against the most famous Apache leader, Geronimo.

Tyson married Bettie McGhee on February 10, 1886 and settled in Knoxville where he taught military science at the University of Tennessee. While teaching at UT, Lawrence D. Tyson enrolled in the college of law and earned a law degree in 1894. Two years later, Tyson resigned his professorship to practice law full-time. Tyson immediately plunged into the business world, becoming the president of the Nashville Street Railway Company. Eventually, Tyson concentrated more and more on business than the law. During his single term in the Tennessee House of Representatives, Lawrence D. Tyson helped to secure the first state funding for the University of Tennessee.

When the United States entered the First World War, L. D. Tyson was quartermaster of the Tennessee National Guard. Tyson immediately volunteered and Governor Tom C. Rye gave the Knoxville businessman command of all state guardsmen. Tyson was commissioned a brigadier general in the U. S. Army, taking charge of the Fifty-Ninth Brigade of the Thirtieth Division, which was known as the “Old Hickory” division. Tyson and his troops trained in South Carolina before departing for France in May of 1918. By July General Tyson and his men were fighting alongside British troops in Belgium. The Tennesseans saw hard fighting, participating in the bloody Somme offensive; the brigade, which had been comprised of 8,000 men saw 3,000 casualties. In late September, General Tyson’s brigade broke through the Hindenberg Line at not only a strategic point, but perhaps also the strongest point in the German defensive line.

Lawrence D. Tyson had much to be proud of, as his troops fought valiantly, earning twelve Congressional Medals of Honor, which was more than any other American division during the World War. Nine of the twelve decorations went to men serving directly under General Tyson. The General was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal.

Still, there was reason for sorrow with the loss of General Tyson’s only son during the World War. It was a loss from which neither General nor Mrs. Tyson ever recovered. After bringing his son’s body back home, Lawrence D. Tyson resumed his business pursuits and turned his eye once again toward politics. Tyson had been a serious aspirant for the United States Senate in 1913 when the legislature still elected senators. Tyson bought the Knoxville Sentinel in anticipation of challenging John Knight Shields for the Senate in 1924.

Perhaps Tyson’s greatest legislative achievement was the Tyson – Fitzgerald Bill. It was only natural a former general would be interested in veterans and the Tennessean sponsored a bill, which granted pension benefits to those emergency army officers with a 30% or greater disability. Under the Tyson – Fitzgerald Bill, those officers received the same retirement privileges as regular army officers. It was also his last legislative accomplishment.

Lawrence D. Tyson had reached the pinnacle of success with his election to the United States Senate in 1924, defeating incumbent John Knight Shields and Judge Nathan L. Bachman for the Democratic nomination. Tyson swept past the GOP nominee, Judge Hugh B. Lindsay, easily in the general election.

At the time of Tyson’s election, senators were not sworn into office until March 3 following the November election. As a newly elected senator, Tyson, accompanied by his senior colleague Kenneth McKellar, visited the White House to “pay his respects” to President Calvin Coolidge. The dour president had just won a handsome election over Democratic nominee John W. Davis. The Nashville Tennessean reported during the course of conversation, the President brought up an appointment to the Interstate Commerce Commission. Coolidge said under the law he was obliged to appoint a Democrat to the vacancy and Senator McKellar immediately proposed the name of General Harvey Hannah, a member of Tennessee’s Public Utilities Commission, an endorsement immediately echoed by Tyson. While Tyson believed they had made a strong case for Hannah’s appointment, Coolidge was unmoved, as he did not make the appointment.

The first issue faced by Tennessee’s new United States senator was a challenge against seating him. A petition signed by various Tennesseans had been presented to the U.S. Senate charging L.D. Tyson had knowledge of lavish spending on his 1924 campaign, which was a violation of existing law. The petition stated Tyson had personal knowledge of expenditures ranging from $250,000 – $500,000 on behalf of his election to the Senate. The petition also alleged there was “evidence of corruption” to be found “in practically every county in the state.” The authors of the petition claimed the huge sums used to elect Lawrence D. Tyson to the Senate closed the door to people of ordinary means. The petition asked the United States Senate to immediately open an investigation into the spending to elect L. D. Tyson.

Senator McKellar pondered taking to the floor of the Senate to defend his junior colleague, but quickly concluded the accusations contained in the petition were “unspecific and so devoid of responsibility” that he thought it unnecessary to make any defense of Tyson. Spending on Tyson’s campaign had likely exceeded the limit under federal law, but proving it was entirely a different matter. The Senate ignored the charges.

Tyson, as a freshman senator, did not have quite as high a profile as McKellar, either in Washington or Tennessee. The General did preside over the dedication of the War Memorial Building in the fall of 1925. Senator Tyson stopped in Johnson City to make an Armistice Day speech on the way back to Washington. Tyson had the pleasure of making an appointment to the Naval Academy due to the failure of an appointee of his predecessor, Senator John K. Shields. Tyson selected J. D. Whitfield, a student at Vanderbilt; Whitfield’s appointment was subject to passing the required examinations.

As 1925 came to a close, Senator and Mrs. Tyson spent the Christmas holidays in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley at the home of their daughter, Mrs. Kenneth Gilpin. The Tysons departed Virginia for their home in Knoxville where the General had pressing business matters to tend to, before returning to Washington, D. C. and the opening of Congress. In an interview with the Nashville Tennessean’s Washington correspondent, John D. Erwin, Senator Tyson said he believed support for the World Court was growing in the Senate.

The World Court was the topic Senator Tyson chose as the subject of his “maiden” speech to the United States Senate in February of 1926. Naturally, Senator Tyson favored not only the World Court, but also American participation. The Bristol Herald-Courier proudly noted both senators McKellar and Tyson not only supported the World Court, but also the League of Nations. The Herald-Courier said, “The overwhelming majority of the Democrats of Tennessee are or were ‘Wilson Democrats’.” The Herald-Courier was certain Tennesseans “believed in Woodrow Wilson and the Wilson Administration.”

Senator Tyson sponsored a bill honoring the three presidents furnished to the nation by Tennessee: Andrew Jackson, James K. Polk and Andrew Johnson. Under Tyson’s bill, the federal government would supply $300,000 to erect statues “or other memorials” of the late presidents in a presidential plaza in Nashville. The remaining $100,000 would be subscribed by Tennesseans. The Nashville Tennessean immediately endorsed Tyson’s bill, lamenting Tennessee was well behind many of her sister states in honoring its own presidents despite the fact the Volunteer State “has more to memorialize” than most states.

Considering Tyson’s military background, it is hardly surprising the General took special interest in veteran’s affairs. As the U. S. Senate considered providing pensions for the veterans of the First World War, Tyson came out in support of the veterans, who he thought had been “mistreated” as the government had “failed to accord them the same rights in pensions that has been accorded other meritorious and deserving men.” Senator Tyson promised to do all he could to bring the bill up quickly for a vote.

Both senators McKellar and Tyson voted against the proposed debt settlement with Italy; the debt was owed the United States from loans made to Italy during the World War. Few countries paid the debts owed to the United States from the First World War.

Senator L. D. Tyson became something of a fixture in speaking to veteran’s associations, as well as dedicating monuments and other tributes to fallen soldiers. When Tennessee’s state librarian, John Trotwood Moore, proposed a “Hindenburg Line World War Exhibit”, Senator Tyson was one of six speakers sought out for the dedication ceremonies. Senator Tyson, along with Senator McKellar, took an active part in an effort to prevent the execution of Bennett J. Doty by the French government. Doty, a veteran of the World War, was facing death by firing squad after having served in the French Foreign Legion under the name of “Gilbert Clare.” Doty, under his pseudonym, had been cited for bravery during the fighting against the Druz tribesmen in Syria. Doty was the son of a Memphis attorney and was accused of having led a mutiny and firing upon French soldiers. Tried and convicted, the mutineers were sentenced to death. Senator Tyson personally visited the French Embassy in Washington on Doty’s behalf while Senator McKellar worked feverishly with the State Department to help the former soldier. McKellar convinced Secretary of State Frank Kellogg to dispatch a telegram to the French government on Doty’s behalf. Kellogg promptly contacted the American Ambassador in Paris, former Ohio governor Myron Herrick, instructing him to intercede with the French government on Doty’s behalf.

The summer of 1929 saw Tyson, along with his colleague K. D. McKellar, receive Tennessee’s public utilities commissioners, Porter Dunlap, Harvey Hannah, and L. D. Hill. The utilities commissioners, popularly elected in Tennessee, journeyed to Washington, accompanied by legal counsel Roy Beeler, to discuss the proposal for developing power and fertilizer at Muscle Shoals, Alabama. The group met in the office of Senator McKellar. The commissioners had not studied the bill drafted by Senator George W. Norris of Nebraska, but worried about protecting Tennessee’s interests. “We are just seeing members of the delegation and getting a comprehensive view of the situation here so as to know what should be done,” Commissioner Porter Dunlap explained.

1929 would be the last year of General Lawrence D. Tyson’s life.