The Irrepressible Perennial

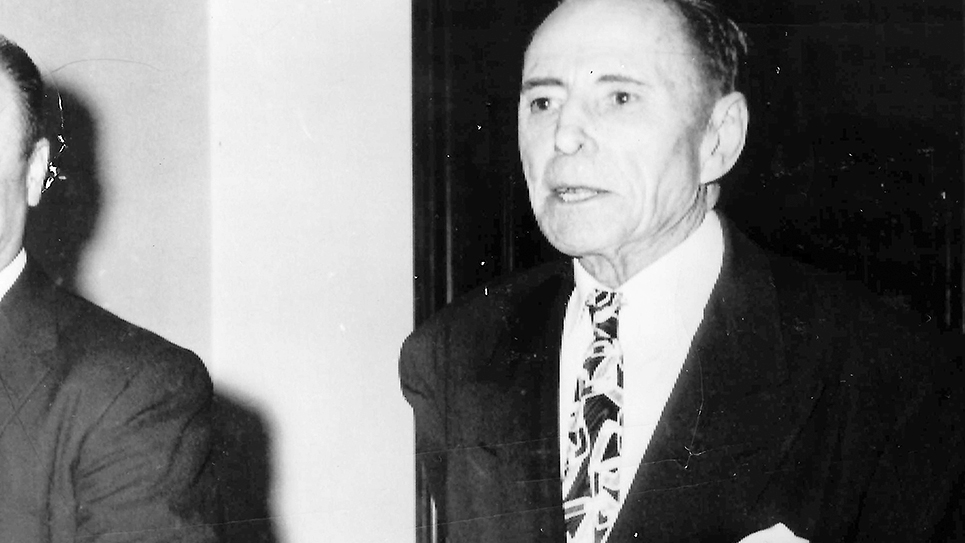

Matthew M. Neely of West Virginia

Faithful readers of this column will note I have covered some of the same subjects again, at least in terms of personages. I am attempting to give readers a better feel for what the person was like, his or her personality. Basically, I am trying to add some flavor to the stew and hopefully I will have achieved my purpose. TIME magazine once described Matthew Mansfield Neely as tall and thin, whose likes included “the New Deal, the C.I.O.” and one who loved “purple language and purple suits.” The news magazine noted Neely “also loves politics, in which he is a shrewd and practical man.” Few politicians demonstrated the flare for the dramatic of Matthew M. Neely. Neely could have just as well be a successful stage actor. Although he delighted in speaking to audiences numbering in the thousands, M. M. Neely disliked crowds and liked leaving just as soon as his speech was finished. From the time he entered Congress in 1913 until his burial in 1958, M. M. Neely commanded center stage in his state of West Virginia and few loved the spotlight more. For quite nearly forty years, Matthew Mansfield Neely was either a congressman, U.S. senator or governor.

In West Virginia it was often said few people had a neutral opinion when it came to Matthew M. Neely. That had been true throughout his political career and remained true even in death. When the longtime senator breathed his last, both the bitter and the sweet were publicly in evidence. From the West Virginia Chamber of Commerce came the wintry blast of “no comment” when asked about Neely’s passing. The “no comment” managed to speak volumes.

One Republican, when told of the senator’s death, exulted “it couldn’t have happened to a better man.” Some of those likely had felt the lash of Neely’s “corrosive tongue.”

No one in modern history has ever made so many political comebacks as Matthew Mansfield Neely of West Virginia. Neely was one of those who had to be in public office, and he was popular enough to come and go with remarkable frequency. One of the most colorful politicians in a state renowned for its oftentimes brutal politics, Matthew M. Neely’s longevity in politics and officeholding was only outdone by Robert C. Byrd in the Mountain State. Yet Byrd was entirely a creature of Congress, serving in both the House of Representatives and the U.S. Senate. M. M. Neely served in both houses of Congress as well, but he also was elected governor of West Virginia. Like Robert Byrd, Neely was a colossus in West Virginia’s stormy political landscape. Unlike Byrd who never lost an election, M. M. Neely knew both the taste of victory and the despair of defeat. The oftentimes flowery orator of the old school could quote from the Bible, poetry, and Shakespeare equally with ease. Even Robert Byrd never dominated West Virginia politics as did Matthew Mansfield Neely. Neely consolidated his hold and was strong enough to elect a protégé to West Virginia’s other Senate seat. The head of the “federal” faction of West Virginia’s Democratic Party, Neely openly sought a candidate for the governorship to eliminate the more conservative “statehouse” wing. None of the prospective candidates suited Neely, so he ran himself.

A lawyer by vocation even if his real trade was holding public office, Matthew M. Neely was the champion of the working folks. A staunch ally of organized labor in a state heavily populated by mine workers and where coalmining was big business, Neely was a warm friend of John L. Lewis, master of the United Mine Workers’ union. Neely’s rise was due in large measure to his phenomenal memory. Even in his eighties, the senator could call people by name whom he had only met casually. While he worked painstakingly on speeches, he was able to read them once or twice and commit them to memory, making it appear to audiences he was speaking extemporaneously.

Neely first came to the House of Representatives in the 1913 special election after Congressman John W. Davis resigned to become ambassador to Great Britain. Reelected in 1914, 1916 and 1918, Neely suffered his first political defeat in the 1920 GOP landslide. Two years later, Neely was the Democratic nominee for the United States Senate held by Republican Senator Howard Sutherland. Neely won the election, only to lose his reelection bid in 1928 to GOP Governor Henry D. Hatfield. Two years later, Neely made a triumphant return to the United States Senate by beating the Republican nominee by the greatest majority given a candidate for the Senate in West Virginia until that time.

With the advent of President Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal, Senator Neely lavishly rewarded his friends and followers with federal jobs. Neely was building a political machine and its effectiveness became clear when he backed Rush Holt against his Senate colleague in 1934. Rush Holt, unable to take the oath of office for six months because he did not meet the constitutional requirement of being thirty years old, defeated Senator Hatfield decisively. By the time Neely came up for reelection in 1936, he and his protégé had become bitter political enemies. Holt, angry that Senator Neely was gorging himself on WPA jobs, took to the Senate floor to denounce West Virginia’s senior senator. Holt claimed Neely was attempting to build up a powerful political machine. Holt endorsed a former Speaker of the West Virginia House of Delegates against Neely in the Democratic primary. Neely beat the stuffing out of his opponent, proving his political machine was running both smoothly and effectively.

West Virginia had been mostly a Republican state until 1932 with the exception of when M. M. Neely was on the ballot. The Great Depression changed the political dynamic in the Mountain State where want and suffering was acute. President Roosevelt was wildly popular in West Virginia and the Republicans were swept out of Congress in 1932 and replaced with New Deal loyalists. The governorship fell into the hands of the Democrats as well. H. Guy Kump became the first Democrat to serve as governor since John Cornwall had gone out of office in 1921. Kump, the Depression governor, was popular as well. Kump picked his successor, Attorney General Homer Hanna, and both administrations were more conservative than Neely’s federal faction. The statehouse faction was busy dispensing its own patronage throughout the state and creating a formidable machine in its own right. Neely recognized the threat to his continued tenure in the Senate and ran for governor in 1940 and beat the statehouse candidate inside the Democratic primary.

That proved to be the peak of Neely’s political potency and power. Neely was even able to appoint his own successor in the United States Senate. Governor Neely selected Dr. Joseph Rosier, a colorless president of West Virginia’s State Teacher’s College. It was readily apparent Neely had picked a placeholder rather than someone who could run for and hold the seat in the 1942 election. Neely had also managed to replace Rush Holt in the Senate, backing an obscure country judge, Harley Kilgore, inside the Democratic primary. Senator Holt, tarred with the brush of isolationism, ran third in a three-way primary between himself, Kilgore and ex-Governor Kump. It soon became clear Neely intended to simply replace the statehouse machine followers with his own and try and reclaim his Senate seat in the 1942 election. Former Governor Kump ran again in the 1942 Democratic primary but nothing or no one could defeat Neely for the nomination of his party.

It took Republican Chapman Revercomb to beat M. M. Neely. The 1942 election was the greatest political surprise of Matthew Neely’s long political career. Governor Neely’s enemies, Republicans and Democrats, supported Revercomb who beat him soundly. Loathing the idea of life without public office, Matthew M. Neely challenged GOP Congressman Andrew Schiffler for reelection in 1944. Grabbing hold of a frail FDR’s coattails, Neely won the election. Two years later, the 72-year-old Congressman M. M. Neely was upset yet again by another Republican. Francis Love won the 1946 election in one of the best years the GOP had enjoyed since the 1920s.

Seventy-four-years old in 1948, M. M. Neely made his greatest political comeback by challenging and ousting his successor in the Senate, Chapman Revercomb. Matthew M. Neely easily turned aside a serious challenger in 1954 and remained in the Senate until the day he died.

Captains and kings felt the sting of Neely’s words. President Eisenhower vetoed a bill raising pay for postal workers 8.8%, and an angry Senator M. M. Neely got to his feet on the floor of the Senate and thundered, “My text consists of the ninth and tenth verses of the seventh chapter of Matthew: ‘What man is there of you, whom if his son asked for bread, will he give him a stone? Or if he ask a fish, will he give him a serpent?’ For 1,900 years these questions remained unanswered. But now every postal employee in the U.S. can identify the man. He is the confused and floundering mythical one who, at the moment, occupies the presidential chair.”

When the 80-year-old Senator M. M. Neely sought reelection in 1954 to another six-year term, coal was facing a noticeable slump. The senator did not especially worry about upsetting those who might admire the occupant of the White House. “In 32 years in Washington, I’ve never seen a more useless President than Dwight D. Eisenhower,” Neely snarled. “He’s the poorest President the U.S. ever had.”

Senator Neely had campaigned throughout West Virginia in 1954 without knowing he had broken his hip at some point. As the pain increased, Neely finally went to the hospital and was told of his fractured hip. The official reason Neely went to Bethesda Naval hospital, according to his office, was an attack of “sciatica.” As is always the case when an aging incumbent is ill, the senator’s office tried to diminish any kind of medical procedure or make it seem routine. Neely’s office acknowledged the senator was undergoing an operation but passed it off as a “minor” surgery. That was in May of 1956; when the new session of Congress began in January of 1957, Senator Neely was rolled into the Senate Chamber in a wheelchair. In June of 1956, Senator Neely had undergone prostate surgery, which was likely for prostate cancer. Neely had lost several fingers on his left hand due to cancer when he was much younger.

As it became more noticeable that Senator Neely might well be seriously ailing, some Democrats urged Neely to retire before Republican Cecil Underwood took the oath of office as governor. Whoever suggested that course of action must not have known Neely well; public office without Matthew Neely was the duller for it, but without public office, Neely was not whole. Senator Neely snapped such suggestions came from his “opposition” or perhaps, he said grimly, from those “friends” who thought they might be the beneficiary of his resigning by being appointed to the Senate.

Matthew M. Neely clung to his seat in the United States Senate with the same tenacity he held onto life. Senator Neely made his last appearance on the floor of the Senate just over a week before he died in Bethesda Naval Hospital of cancer. Neely’s political career only ended with his last breath. No funeral rite, except perhaps for a fiery Viking send off, could do justice to Matthew Neely’s colorful personality. There had been nothing sedate nor especially stately about M. M. Neely.

Senator Neely’s body lay in repose at his home in Fairmont. M. M. Neely likely would have been skeptical about the numerous tributes offered to him in death. “Old Matt” Neely probably would have liked that offered up by an anicent ward heeler, who opined simply, “He was the greatest vote-getter of them all.”

© 2024 Ray Hill