“Live so that when you die, even the undertaker will be sorry.”

Sign that hung in the business office of Jim Cummings.

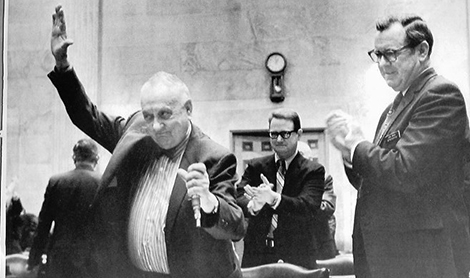

James H. Cummings is likely a name unfamiliar to most readers, but during his time he was a power and a man to be reckoned with. When he died in 1979, “Mr. Jim” Cummings had served longer in Tennessee’s state legislature than any other man in our state’s history. Living in the tiny hamlet of Woodbury, Tennessee, Cummings influenced events and pushed rural interests while serving in the legislature. Jim Cummings was powerful enough in Nashville to vex Edward Hull Crump, master of the Shelby County machine and was a strong supporter of Tennessee’s influential U. S. Senator Kenneth McKellar, while also allied with McKellar’s political nemesis Gordon Browning. Always colorful, “Mr. Jim” joined with two other long-serving rural legislators, I. D. Beasley of Carthage and W. D. “Pete” Haynes of Winchester, Tennessee. The three constituted a powerful bloc inside the legislature, promoting rural interests and were widely known as the “Unholy Trinity” by those who had the misfortune to tangle with them, either singularly or collectively.

James H. Cummings was born November 8, 1890 and like many young men of the time, Cummings taught school, earning $35 a month and recalled, “I remember carrying water and wood to the school house. I decided then that there had to be a better way.”

The better way for Cummings was becoming Circuit Court Clerk in 1912. While serving as Clerk, Cummings also became the publisher for the Cannon Courier. Cummings left office in 1920 and accepted a job in the State Comptroller’s office in Nashville while attending the YMCA law school at night. Admitted to the bar in 1922, Jim Cummings went to Cumberland University in 1923 where he received his diploma. A real estate boom in Florida lured Cummings to the Sunshine State where he went to work for a developer in 1925. The boom went bust in 1927 and “Mr. Jim” came home to Woodbury where he opened a law office and began five decades of practice as a country lawyer. “I learned a lot down there,” Cummings said of his time in Florida. “One of the things I learned was I couldn’t get along without Hesta.” Cummings was referring to Hesta McBroom, a local girl whom he married. “Miss Hesta” ran a small insurance business out of the Cummings law office.

Jim Cummings went to Nashville in 1929 having been elected to serve as the state senator from a small cluster of counties surrounding his own Cannon County. For the next forty years, Jim Cummings would be a fixture in the legislature with the exception of four years when he served as Tennessee’s Secretary of State and two years when he opted not to run, as he was managing Gordon Browning’s unsuccessful gubernatorial campaign in 1938.

“I always figured Nashville and Memphis, with their big delegations would take care of the urban areas in the legislature,” Jim Cummings once recalled. “Well, I lived on a little dirt road, and I figured I could do something for the rural counties.” Cummings, along with his allies I. D. Beasley and “Pete” Haynes frequently frustrated the aims of the urban interests led by E. H. Crump and Hilary Howse, Nashville’s mayor. Crump was particularly appalled that legislators like Jim Cummings (as well as governors like Austin Peay) collected money from the urban counties and spent it in the rural counties. Although Jim Cummings admired Senator McKellar, his admiration did not extend to Mr. Crump. Cummings oftentimes referred to his native Middle Tennessee as “free Tennessee.” The triumvirate of Cummings, Beasley and Haynes, according to the Nashville Tennessean, “operated together like a well-oiled, if miniscule political machine.” As each of them accumulated experience, each gained contacts and an exhaustive knowledge of parliamentary procedure, allowing the “Unholy Trinity”, united or occasionally one of them alone, “on occasion to outmaneuver the entire 132-member legislature, and the governor and the Crump political machine to boot.”

Cummings once sent Governor Prentice Cooper and Crump into a spiral in 1941 when he suddenly demanded all bills in committee be brought to the floor for disposal. Nor were any of the three, especially I. D. Beasley, above playing pranks on anyone and everyone. Governor Buford Ellington remembered, when any of the three legislators paid him a visit “the first thing I’d do was hide my personal memo pads. If I didn’t, they stole them and used them for their own purposes.” Ellington was referring to a longstanding habit where one of the three would forge a note from the governor, almost always when there was a close vote pending on the floor, which urgently requested a legislator on the other side come to the governor’s office or for a special conference in a Capitol hideaway. By the time the puzzled legislator finally figured out the governor had not summoned him, the vote had been taken and recorded.

Ellington realized the strength of the three rural legislators. “If those three decided to kill you on a particular bill, they could kill you,” Ellington recalled. “It’s as simple as that. They could scan a bill in a few minutes and tell anyone exactly what was in it. They were experts on parliamentary procedure, and could tie up a session in giant knots of red tape if they were against a bill being considered.” Cummings served as Ellington’s floor leader in 1959.

The 5’3” and 230 pound I. D. Beasley died in 1955 and if anything, he was even more colorful than “Mr. Jim” Cummings. Beasley was remembered as “the Mockingbird of Capitol Hill” for his uncanny ability to mimic anyone, man or woman. Supposedly, Beasley was such an excellent mimic, a man’s wife could not tell the difference.

When Beasley took the oath of office that same year, it marked his thirteenth term in either the state senator or house, a record later broken by Jim Cummings. Beasley had impersonated the voice of Frank “Roxy” Rice, Crump’s generalissmo in charge of legislative affairs to dupe a fellow legislator from Chattanooga. Pretending to be Rice, Beasley proceeded to tell D. M. Coleman Crump had changed his mind and was supporting Pete Haynes to be Speaker of the House. Crump had gone to Hot Springs, Arkansas to revive himself, while Roxy Rice went to Pasadena, California to watch the Rose Bowl game. It did not take either the Memphis Boss or Frank Rice long to figure what had gone awry. Pete Haynes became speaker by Beasley’s deception, much to Crump’s dismay and displeasure.

D. Beasley also caught a blind legislator on the steps of the Capitol and impersonated Governor Austin Peay and asked the poor fellow to change his vote, which he did.

Nor was Jim Cummings safe from his friend I. D. Beasley. Sharing a hotel room while the legislature was in session, Jim Cummings had gone to bed and was asleep when Beasley convinced an obliging drug store clerk to fill his mouth liberally with toothpaste and foam at the mouth. Beasley switched on the lights and began screaming bloody murder. Cummings came awake staring into the face of the frothing clerk and leaped out of bed, grabbing a chair and shrieking, “Kill him! Kill him!”

No one was safe from Beasley pranks and district attorney Baxter Key remembered, “One day a stranger came to town looking for me and I.D. told him I was deaf – – – that I could hear only if he shouted at the top of his lungs. That was 30 years ago and I can hear it yet.”

Jim Cummings explained the alliance years after I.D. Beasley had died and Pete Haynes had retired. “We were three country lawyers connected by our interest in rural Tennessee. We tried to work together for the common good.” Cummings’ philosophy was simple. “I believe in collecting the taxes where the money is – – – in the cities – – – and spending it where it’s needed – – – in the country,” Cummings said before adding, “Now that’s not as unreasonable as it sounds.”

Friend or foe, Jim Cummings managed to keep more or less cordial relations with every governor, save for Prentice Cooper. Once, in a fit of pique, Governor Cooper denounced a statement of Cummings as “the howl of a disappointed, hungry politician.” Cummings could hold his own and snapped back the governor was merely playing the “role of a hit dog” and was speaking “for his masters”, meaning E. H. Crump.

When Gordon Browning made his triumphant return to Nashville after a decade out of office, Jim Cummings was elected Secretary of State. Although Browning attempted to win a third two-year term in 1952, Cummings was running for the legislature once again. Cummings promptly became Governor Frank Clement’s floor leader. When Cummings announced he wanted to become Speaker of the House in 1967, all the other candidates promptly withdrew. At home, no one ever bothered to run against Jim Cummings, such was his personal popularity.

The last years of Jim Cummings’ service in the Tennessee House of Representatives were devoted to fending off legislative reappointment, a battle he eventually lost. As long as the battle was confined to the state legislature, Jim Cummings was able to keep reapportionment at bay. It took a federal court to best Jim Cummings. After 1963, Cannon County would not have its own representative in the legislature and Cummings realized with the addition of the more populous Rutherford County to his district, his days were likely numbered. Yet, Jim Cummings endured for another decade. Cummings remained adamant in his disdain for apportioning representatives on the basis of population. “We must not allow numerical concentrations of people to be the sole gauge of the number of representatives alive. It’s not healthy,” Cummings complained.

He remained a spokesman for rural interests, confessing, “I guess I’ll always see things from this side of the bank.” Cummings did not see that rural problems were that much different from those plaguing the cities. “I mean, they have problems in the cities with ghettoes, but we have them of sorts, too. There are houses around here where a dog could jump through the cracks.”

Never having lost an election and past eighty, Jim Cummings announced in 1972 he would not be a candidate for reelection to the Tennessee House of Representatives. James Lanier, a fellow legislator, said, “He was probably the most shrewd and astute politician I’ve ever known” yet said Cummings had a gentleness about him. Still, despite his increasing years, Jim Cummings remained a chain smoker, frequently lighting one cigarette from another. Nor did “Mr. Jim” lose his fondness for libations. Cummings enjoyed an overflowing liquor cabinet on the floor of the House chamber until an inquiring reporter finally exposed its existence. Lanier marveled that Cummings stamina, noting the veteran legislator “could go with the youngest man up there all night long and sit through committee meetings all the next day.”

Following retirement, a wing of the War Memorial Building was named for Cummings and the legislature met in special session in Murfreesboro, Tennessee to name a dormitory in his honor.

Serving with eight governors, “Mr. Jim” began to wear out from old age. Ill, Cummings went to St. Thomas Hospital in Nashville for surgery and continued to fade. He died a week before his eighty-ninth birthday.

For forty years “Mr. Jim” Cummings had worked for the interests of rural people all across the State of Tennessee and was a devoted friend to education especially. The lives of the people his service encompassed and touched are impossible to measure, but they and their descendants still walk amongst us. When “Mr. Jim” died, even the undertaker was sorry.