By Ray Hill

From 1931 until 1947, the Republican Party had suffered shattering defeats largely brought on by the Great Depression. Following the 1936 election, where GOP presidential candidate Alf Landon only won the electoral votes of Vermont and Maine, Republicans in the House of Representatives constituted only 88 members.

Throughout the decade of the 1920s, Republicans had enjoyed healthy majorities in both houses of Congress, which had been progressively thinned out until the Democrats controlled both the House of Representatives and the United States Senate. The last Republican Speaker of the House had been Nicholas Longworth of Ohio. A highly personally popular Congressman, Nick Longworth was known for his marriage to Alice Roosevelt, the tart tongued eldest child of the late President Theodore Roosevelt. Longworth, bald, mustachioed and an accomplished violinist, was also known for his sense of fun. Longworth had died suddenly in 1931 and due to the deaths of several other GOP congressmen and a series of special elections won by Democrats, John Nance Garner of Texas became Speaker of the House.

Not until 1947 would the Republican reclaim a majority in the House of Representatives. From 1931 until 1995, the GOP only managed to retain a majority of Congress twice and then only for two years each time.

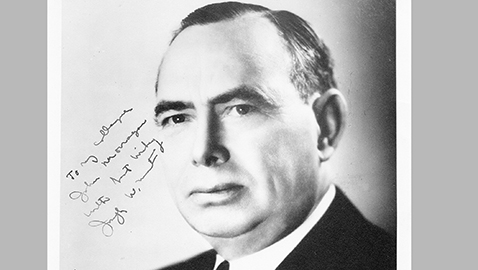

Joseph W. Martin was the Republican leader in Congress from 1939 until 1959.

At the time of his death, one obituary writer commented that Joe Martin had “one of the blackest scowls and brightest smiles in Congress.”

That same author pointed out something rather curious about Joe Martin’s long Congressional career: “Yet despite his acknowledged political abilities and leadership, Representative Martin never had his name on an important piece of legislation; never made a memorable speech; never achieved the fame or public affection of his Democratic counterpart, Sam Rayburn of Texas.”

Joseph W. Martin was a diminutive, rather dumpy little fellow who had first been elected to Congress in 1924, after climbing the political ladder in his native North Attleboro, Massachusetts. Martin worked very hard throughout his life; he had been a good enough athlete to play for a semiprofessional baseball team and earned the princely sum of $10 per game. He was still only a lad when he began working for the North Attleboro Evening Chronicle as a delivery boy. Over time, Martin would become the editor and finally the publisher of the newspaper. Martin was offered a scholarship to Dartmouth College, but preferred to remain at the Evening Chronicle, as he helped his parents put his brothers through school. Earning $10 a week as an employee of the paper, he saved his money and bought the Evening Chronicle, which he kept for the rest of his life.

By 1912, Martin had been elected to serve in the Massachusetts House of Representatives and won a promotion two years later to the State Senate. Joe Martin chose not to run again in 1916.

Martin had been out of office for eight years when he challenged eighty-three year-old incumbent in the Republican primary and won. Joe Martin would remain in Congress for more than forty years.

Martin worked his way up through the GOP ranks and when Republican leader Bertram Snell of New York retired in 1938, Joe Martin was selected to succeed him. The 1938 elections had improved the fortunes of House Republicans, as they had won 72 seats in that fall.

Congressman Martin was, as might be expected, largely opposed to Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal, but he demonstrated considerable ability in working with the majority Democrats when necessary. Long marginalized, Martin helped to forge an alliance with conservative Southern Democrats, which gave both a voice in the House and made that voting bloc a force to be reckoned with. Martin’s own voting record was hardly reactionary, as he had voted for the Social Security legislation, although he was deeply opposed to the Tennessee Valley Authority.

In 1940, Joe Martin assumed the Chairmanship of the Republican National Committee, at the request of GOP presidential nominee Wendell Willkie. It was an experience that somewhat dismayed the little man from Massachusetts, having been a rock-ribbed Republican all his life, especially as Willkie had been a Democrat for the most of his own life. Willkie ran much better than had the previous two Republican presidential nominees, Herbert Hoover and Alf Landon, but still lost decisively to Franklin Roosevelt, despite some resistance to FDR seeking a third term.

Martin got some unwanted attention during that campaign when President Roosevelt made a famous speech excoriating the GOP, repeatedly using the phrase, “Martin, Barton and Fish,” three Republican congressmen, that was highly effective.

The 1942 midterm elections reduced the number of Democrats in Congress even further and Joe Martin’s coalition of Republicans and Southern Democrats grew more powerful. Martin was quite friendly with his counterpart, Speaker of the House Sam Rayburn. The two were warm personal friends.

After losing another election in 1944 to Franklin Roosevelt, the GOP made a spectacular comeback in 1946, running on the slogan of “Had Enough?” It was a reference to the deprivations suffered by Americans throughout World War II. Shortages of meat, butter, tires, women’s stockings and many other items vexed Americans and President Harry Truman was unpopular. 1946 was one of those rare tidal wave elections and the GOP gained control of both the House of Representatives and the United States Senate.

Joe Martin was elected Speaker of the House by his Republican colleagues, ousting Sam Rayburn. As the 1948 elections approached, Republicans were utterly confident of holding their majorities in Congress, as well as electing New York governor Thomas E. Dewey president. Nobody seemed more confident than Dewey himself and while he had run a good race against that champion vote-getter, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Dewey did not wage a hard hitting campaign. Rather, Dewey campaigned almost as if he were an incumbent. Speaker Martin accompanied Dewey on several of the nominee’s trips across the country and it was Martin’s elderly mother who surprised everyone by scolding the governor about his campaign strategy. Mrs. Martin told a surprised Thomas E. Dewey he could not merely assume he was as good as elected. The outspoken old woman informed Governor Dewey he was far too complacent. Her prediction proved to be all too accurate. The scrappy little man from Missouri waged the kind of campaign Dewey himself should have run and won the election, much to the surprise of almost everyone. Even more shocking, the Democrats won back control of both houses of Congress. Joe Martin would have to surrender the Speaker’s gavel back to Sam Rayburn.

Things would change again in 1952 when the hugely popular Dwight D. Eisenhower won the GOP presidential nomination in a bitter contest with “Mr. Republican,” Ohio Senator Robert Alphonso Taft. Taft had competed for the Republican presidential nomination twice before and lost. Many Republicans realized it was Taft’s last chance to seek the presidency and despite being a sentimental favorite of many delegates, even more believed Eisenhower could bring them victory. Unfortunately, Taft was not destined to live much longer, dying of cancer the following year.

General Eisenhower’s personal popularity enabled him to make inroads in some Southern states; he carried Tennessee, Texas, Virginia and Florida. With Eisenhower’s election, the House and Senate reverted back to GOP control. Once again, Joe Martin was elected Speaker of the House.

Yet again, it was but a brief interlude. The 1954 elections reversed Republican fortunes and Martin had to vacate the Speaker’s chair for Sam Rayburn. The Texan was magnanimous to Martin and pointed out they had switched offices so frequently that perhaps Martin should continue to occupy the Speaker’s sumptuous suite of offices in case they had to move once again. For the rest of his time as Republican leader, Joe Martin occupied the Speaker’s office, irrespective of whether he actually was the Speaker of the House.

Joe Martin had done everything he possibly could to advance President Eisenhower’s legislative agenda in the House, unlike many Republican senators who surprised the former general by opposing many of his initiatives. Had it not been for the frequent cooperation of Democratic leader Lyndon B. Johnson, Ike would have had a very difficult time getting anything done.

Joe Martin’s political undoing was the 1958 elections. Off year elections are historically hard on the party in power and the United States had sunk into a deep recession, making it much more difficult for Republican incumbents that year. The 1958 elections was a disaster for the GOP. Republicans lost thirteen seats in the U. S. Senate; just a year later, the Democrats would win three of the four Senate races for the newly admitted states of Alaska and Hawaii. The debacle in the House of Representatives was little better, as the Republicans lost forty-eight seats. The defeat was staggering for the GOP.

Disgruntled Republicans who had been fortunate enough to survive the 1958 elections were rumbling louder about replacing Joe Martin as the GOP leader in the House. At first, Martin foolishly dismissed the rumblings as just a few unhappy young congressmen. The burgeoning revolt was actually spearheaded by Indiana Congressman Charles Halleck, the Minority Whip in the House. Halleck had considered challenging Joe Martin for the top spot at least a couple of times before, but could not get past President Eisenhower, who did not look favorably upon deposing Martin.

Halleck gave a quiet dinner for three White House aides and casually brought up the topic of replacing Joe Martin as Republican leader. None of the three were ready to say the president would support removing Martin. Just a few days later, the situation changed. Apparently surprised by the scope of the Republican defeat, President Eisenhower made it clear to Charles Halleck he would not take part in any contest for the Republican leadership in the House of Representatives. Without the active or tacit support of Eisenhower, Joe Martin was vulnerable.

Halleck beat Joe Martin and a dejected and surprised Martin left the Republican caucus depressed.

A bachelor his entire life, Joe Martin neither drank alcohol, smoked or even danced. According to the late Doorkeeper of the House, William “Fishbait” Miller, Martin “didn’t do anything.” Serving in Congress was pretty much the sum total of Joe Martin’s life.

Following his defeat by Halleck, Joe Martin was something of a lonely and pitiful figure. While still a member of Congress, Martin was bereft of the power he had once exercised as Speaker and Republican leader. For the rest of his Congressional career, Joe Martin was relegated to the sidelines.

Martin contented himself by penning a lively and entertaining autobiography entitled, My First Fifty Years In Politics. Congressman Martin remained somewhat bitter about the lack of support he had received from President Eisenhower in losing his leadership position.

Charlie Halleck would suffer an almost identical fate to that of Joe Martin. After the Republicans lost the 1964 elections, a group of young congressmen would support Congressman Gerald Ford of Michigan and topple him from his leadership role.

Yet there was one final bitter disappointment awaiting Joe Martin.

Past eighty, in precarious health, Congressman Joe Martin was challenged in the 1966 Republican primary by Margaret Heckler. Mrs. Heckler, a perky redhead, was a very attractive candidate and had served on the governor’s Council in Massachusetts. Forty-six years younger than Congressman Martin at the time, Mrs. Heckler radiated youth and vigor. Martin, realizing he was in trouble, announced if elected, it would be his last term in office. Although Martin was no mossback, Mrs. Heckler was not only more modern, but also more liberal. The challenger effectively used press clipping gleaned from Joe Martin’s own first race against an eighty-three year-old opponent. There were accusations Martin was in ill health and was spending more time in Florida than in Washington, D. C.

It was a hard fought campaign and while Joe Martin struggled, in the end, he lost.

Ironically, Congresswoman Heckler would be confronted by a more progressive opponent herself when she was redistricted into a district with Congressman Barney Frank. Heckler would lose that race and go on to serve in the Cabinet of President Ronald Reagan.

After losing his seat in Congress, Joe Martin’s health continued to deteriorate and he lived just over a year after leaving Congress. Joe Martin died on March 6, 1968.