By Ray Hill

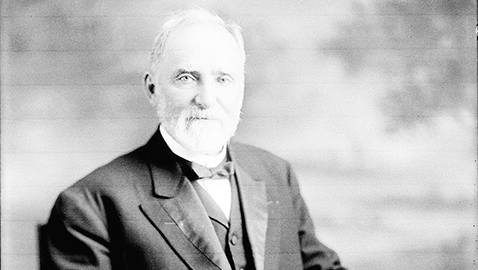

Most Knoxvillians have heard of the Webb School, but few remember William Robert Webb, the founder and headmaster of the first Webb School.

R. Webb was a formidable character by any standard; he was a professional educator throughout his life, as well as a community activist and briefly, served as United States senator from Tennessee.

Webb was born on November 11, 1862 in North Carolina. His father died when Webb was only six years old, but the future educator’s mother managed to raise him and his siblings. Mrs. Webb instilled in her son that hard work was the foundation for all success in life, but she also stressed learning the qualities that comprised being a gentlemen were essential to good character. W. R. Webb would remember the lessons taught to him by his mother and the graduates of his own school would not only be well educated, but they would be gentlemen. Another lesson from his childhood that W. R. Webb never forgot was beginning the day with a prayer and the reading of the Bible.

Webb was attending the University of North Carolina when the Civil War broke out and he left his studies to enter the Confederate Army as a private. William R. Webb endured just about every terrible experience the Civil War had to offer: deprivation, a serious wound, imprisonment and escape. After having received a sever wound in his shoulder in the battle fought at Malvern Hill, Webb used the time allotted to him to recover by returning to the University of North Carolina.

R. Webb did not linger long at the university and once again abandoned his studies to fight for the Confederacy. Webb joined a cavalry regiment and rose through the ranks to become a Captain. Webb was captured and imprisoned in New York, but escaped.

After the end of the Civil War, William R. Webb returned home, riding in the boxcar of a train. Webb resumed his life as a civilian and kept himself quite busy supporting his family, helping his brother, John, get an education. Webb served as a schoolmaster and watched proudly as John proved to be an especially gifted student and would later join his older sibling at the Webb School.

William R. Webb married Emma Clary in 1873 and their union produced eight children. Most of the Webb children lived long and productive lives; one, Susan, lived to be almost one hundred years old, passing away in 1980. Webb’s oldest child, William Robert “Will” Webb, Jr., would succeed his father in running the Webb School and oftentimes stepped in when the elder Webb was ill or away. Another Webb child, Thompson, moved to California where he established the Webb Schools in the Golden State.

Unhappy in North Carolina due to the harsh reconstruction government, W. R. Webb moved to Tennessee, settling in Culleoka. When Vanderbilt University was through a million dollar gift from “Commodore” Cornelius Vanderbilt, the wealthiest man in the country, at the time, many, if not most, of its most outstanding graduates had attended the Webb School.

R. Webb was an ardent prohibitionist, as well as a strict schoolmaster. Webb frowned upon the smoking of cigarettes, disliked the use of profanity, and positively abhorred gambling. When Culleoka allowed the sale of liquor, W. R. Webb was incensed. As a result, Webb moved his school to Bell Buckle, Tennessee. The citizens of Bell Buckle were thrilled to have the Webb School in their community and $12,000, a considerable sum for the time, was raised to make the move possible.

While Webb was quite strict, he also strongly encouraged his students to be an individual and independent thinkers. “Don’t be a me-too!” Webb frequently told his students.

The Webb School quickly gained a national reputation as one of the best preparatory schools in the country, sending well-educated young men to the best colleges and universities in America. The Webb graduates were noted not only for their learning, but their gentlemanly traits as well. No less than Woodrow Wilson, a future President of the United States and head of Princeton University, believed the Webb School to be an especially fine school.

R. Webb experienced some serious problems with his health in 1908 and that necessitated his taking a leave of absence from his school while his son Will assumed his duties as headmaster. Webb soon recovered his health and returned to his school some months later.

William R. Webb was never a politician. While he was interested in the issues affecting his community and state and was certainly profoundly interested in the cause of prohibition, Webb never sought any office. W. R. Webb was caught up in Tennessee politics through an unusual set of circumstances. Senator Robert Love Taylor died unexpectedly ion March 31, 1912 following a routine operation. Tennessee had a Republican governor, Ben W. Hooper, who appointed Newell Sanders to fill the vacancy on April 11, 1912.

Newell Sanders had been Hooper’s mentor and was a power in Tennessee’s Republican Party. Sanders was loathed by many Democrats, as the Chattanooga manufacturer was a highly partisan Republican. Sanders served from his appointment in April until the following January when the Tennessee General Assembly elected William R. Webb to serve the remaining two months of the term.

R. Webb was highly respected by just about everyone in Tennessee and his election to serve a very brief term in the United States Senate was, as expected, widely hailed. Webb offended no particular faction inside his own party and even Republicans could say little critical of the stern schoolmaster. Despite Webb’s election, the full six-year term went to Democrat John Knight Shields, a justice of the Tennessee State Supreme Court, who had the backing of the powerful “fusionist” movement. The fusionists were a combination of Independent Democrats and Republicans who had won Tennessee’s other Senate seat and elected Ben W. Hooper governor in 1910. Hooper was reelected in 1912 and the fusionists would dominated Tennessee’s politics until 1914.

Senator Webb did little more than take his seat in the United States Senate and collect his pay. Webb made one speech on prohibition, a favorite topic for the educator. Webb did introduce one bill while a member of the U. S. Senate, to prohibit the desecration of the flag of the United States.

With the expiration of his term on March 4, 1913, William R. Webb returned to Bell Buckle and his school.

It was the crowning achievement of his career and for the rest of his life, Senator Webb remained a beloved figure in Tennessee. His nickname of “Old Swaney,” according to Senator Kenneth McKellar’s book on Tennessee senators, was bestowed upon Webb during his childhood. Evidently “Swaney” was a derivative of Alexander, which was Webb’s father’s name and while another Webb’s son was named for their father, it was W. R. Webb who got the nickname.

McKellar was a Congressman during the brief time W. R. Webb served in the Senate. A couple of years after Webb returned to his school, McKellar was running for the Senate against the incumbent, Luke Lea. McKellar visited with Webb, who was gracious, but told the Congressman he was very strongly for Senator Lea. Webb mentioned he knew Senator Lea quite well, while he did not know McKellar especially well. Webb also pointed out Luke Lea was a strong prohibitionist. Senator Webb was strongly opposed to McKellar’s other opponent in the race, former governor Malcolm R. Patterson, who had been opposed to prohibition while Tennessee’s chief executive.

McKellar recalled in his book there were few other places in Bell Buckle for a candidate to speak outside of the Webb School and the Congressman asked Webb’s permission to use the building. Webb agreed and McKellar asked the headmaster if he would not come and hear his speech. McKellar recalled as he talked about Senator Lea’s record “the old gentleman” was “quite nervous.” McKellar said, “He crossed his legs scores of times, and was obviously excited and ill at ease.” Yet when McKellar went on the attack about Patterson, Senator Webb’s attitude was transformed. Webb was “one of the most vigorous and active of the applauders” during McKellar’s assault on the former governor.

R. Webb was highly interested in the outcome of the first popular election of a senator from Tennessee. The 1915 primary was hard fought between McKellar, Senator Lea and former governor Patterson. McKellar recounted a story told him by State Senator Crockett Bingham, who remembered William R. Webb being driven to a store he owned in his Packard limousine. The former senator came into Bingham’s store and invited him to accompany him on a drive. The two made small talk as the chauffeur drove them around town before heading up to the cemetery where Senator Bingham’s father was buried. Webb suggested they visit Senator Bingham’s father’s grave and they were both leaning on the railing when Webb said, “Crockett, your father was a fine man – – – a very fine man. he was the soul of truthfulness, honor and integrity.”

Bingham agreed and then the former senator demanded to know how he thought the primary election would shake out. Bingham speculated that Senator Lea would easily win the district, followed by former governor Patterson, with McKellar a very poor third. McKellar carried the district and Senator Lea ran a poor third.

Once again Senator Webb’s Packard limousine glided up to Crockett Bingham’s store and the old schoolmaster got out and sighed, “Ah, Crockett! Ah, Crockett! I did think you’d tell me the truth standing by your father’s grave. Ah, Crockett! Ah, Crockett!

“You did not tell me the truth, Crockett!”

As a schoolmaster, “Old Sawney” was not only intent upon teaching his boys, but apparently had a positive genius for fitting a punishment to the crime. When one errant youngster had sneaked away to go fishing, he returned to find himself caught. Webb gave the boy a stick, a length of string and a bent pin and made the young fellow fish in a rain barrel for most of the day.

R. Webb served on the Bedford County draft board during World War I and there was nobody who was thought more high minded and fair than the old schoolmaster.

The years crept up on “Old Swaney” and in December of 1926, at the age of eighty-four, he died at his home. The tributes poured in from his former students, as well as others whose lives he had touched in some way. Several noted the little school W. R. Webb operated in the piney woods of Tennessee produced more Rhodes Scholars than any other secondary educational institution in its first fifty years.