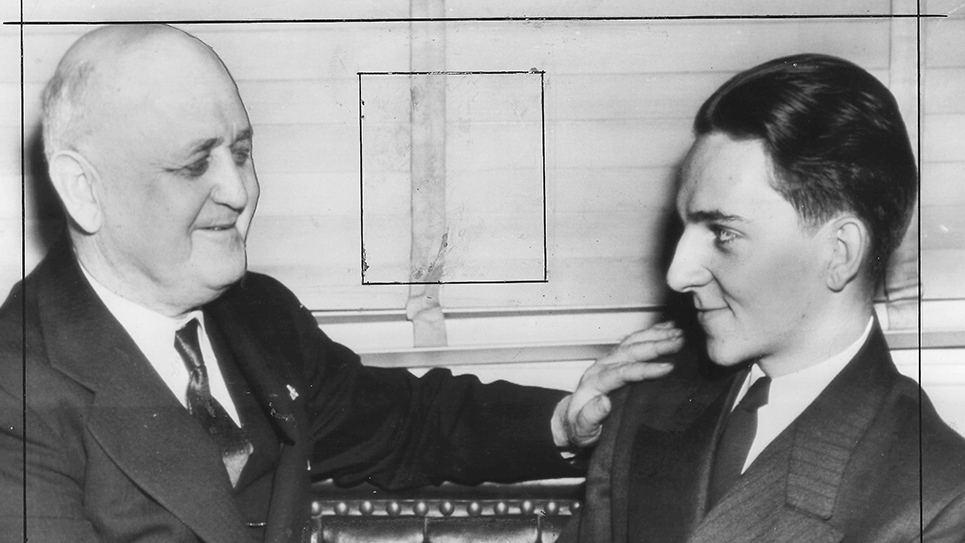

Robert L. Ramsay of West Virginia

By Ray Hill

I have oftentimes stated my belief that the U.S. House of Representatives, for better or worse, is a reflection of those people who send a congressman to Washington, D.C. Most congressmen work in anonymity, even in today’s world where there are too many news and social media outlets to count. Usually, those representatives were only widely known inside the congressional district they represented. Robert Lincoln Ramsay was one of those representatives who was little known outside of West Virginia’s First Congressional District. Ramsay immigrated to the United States with his parents in 1881, when he was four years old. The future congressman’s father was a miner, which was the perfect pedigree for a Democrat in West Virginia where the unions would become a powerful political entity in the coming decades. The family settled in Hancock County and Robert Ramsay graduated from the West Virginia University College of Law in 1901. For the rest of his life, Ramsay would practice his chosen profession in one form or another.

Prior to the Great Depression, West Virginia was a Republican state and Ramsay’s party was in the minority, although it was possible for a Democrat to win elections periodically as demonstrated by the irrepressible Matthew M. Neely, who was both a perennial and frequently successful candidate for public office. Ramsay served as the city solicitor of Follansbee for a lengthy period of time and was elected the district attorney for Brooke County in 1908 and served four years before losing his reelection campaign. Bob Ramsay would prove to be something of a perennial seeker of office himself and defeat never deterred him from his goals. Four years after having lost his reelection bid as district attorney, Ramsay ran again in 1916 and won. In 1928, Ramsay was the Democratic nominee for attorney general of West Virginia, but it was a big year for Republicans in West Virginia and the nation. The entire Democratic ticket, including U.S. Senator Matthew M. Neely, went down to defeat. Bob Ramsay lost to incumbent Attorney General Howard B. Lee by more than 63,000 votes.

Two years later, Ramsay challenged Congressman Carl Bachman, a Republican, for his seat in the U.S. House of Representatives. Even with the Depression, Bachman managed to win reelection relatively easily, garnering better than 56% of the ballots cast. As always, Bob Ramsay was persistent and ran again for Congress in 1932. With the Great Depression deepening and more people suffering, West Virginia voters began to turn away from President Herbert Hoover in particular and the Republican Party in general. As Franklin Roosevelt was carrying the Mountain State with 54.4% of the vote, Robert L. Ramsay was edging out Carl Bachman in what was likely the most solidly Republican congressional district in West Virginia. Ramsay eked out a 3,000-vote victory in the general election.

Once in Washington, D.C., Bob Ramsay was a loyal supporter of President Franklin Roosevelt and the New Deal. Congressman Ramsay was also an unabashed supporter of organized labor, a prerequisite for any Democrat in West Virginia. Former Congressman Carl Bachman, likely thinking Ramsay’s win in 1932 had been a fluke, sought a rematch in the 1934 election. Ramsay increased his majority, beating Bachman decisively. In 1936, Congressman Ramsay won by the biggest majority of his congressional career to date, polling almost 60% of the vote against GOP candidate Charles J. Shuck.

Bob Ramsay had every reason to feel good about his reelection campaign in 1938; he had steadily increased his majority with every election. Republicans nominated attorney Andrew C. Schiffler without opposition to face Ramsay in the general election. Election Day surprised Congressman Robert Ramsay, who was upset by Schiffler, who won by quite nearly 10,000 votes. As always with the defeat of an incumbent who is expected to win reelection, local newspapers unearthed the body to do a political autopsy. Referring to Ramsay as the “Friar of Follansbee,” columnist Charles Brooks Smith of the Hinton Daily News thought Ramsay had fallen victim to the unpopularity of Secretary of State Cordell Hull’s trade treaties inside the district. Smith opined the trade treaties were a significant issue both in Ramsay’s district as well as that of the Eighteenth District in Ohio, which lay across the river. Noting that Wheeling, inside West Virginia’s First Congressional District, was “a compact, populous center of highly unionized crafts of ‘skills,’” the tariff was “no academic question to those workers. Both districts had Democratic congressmen, Ramsay and Lawrence E. Imhoff of Ohio; both lost their reelection campaigns to GOP challengers in the 1938 election. As a loyal supporter of the New Deal, enough unemployed workers blamed Ramsay for their condition due to Hull’s trade policies. Congressman Ramsay had stoutly resisted the arguments made by many glass workers in the First District, who had become unemployed due to the imports allowed under treaties negotiated by Secretary Hull. Ramsay maintained those treaties were not the cause of their losing their jobs while A.C. Schiffler took the opposite approach, steadily lambasting the New Deal and its trade policies. As Charles Brooks Smith wryly pointed out, an unemployed worker on a steady diet of beans is unlikely to care much for lofty economic arguments. Ramsay’s insistence he would not question “any policy now effect in Washington” was utterly unacceptable to those on relief instead of working.

An editorial in the same newspaper faulted a decision made by the National Labor Relations Board in a hearing on Weirton Steel, which was related to charges the company had discriminated against organized labor and unions. The editorial thought the resulting investigation “was so biased and unfair it brought about a revulsion of feeling among the voters of both parties in the northwest panhandle of the State.” As the Hinton Daily News rightly concluded, Congressman Robert L. Ramsay had been no less supportive of the New Deal than the rest of West Virginia’s congressional delegation, with the notable exception of maverick U.S. Senator Rush Holt.

Rarely ever does an election turn upon a single issue; usually it is a combination of factors and 1938 was the beginning of the end of Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal. For six years, Democrats had increased their majorities in both houses of Congress and the 1938 election saw the tide ebbing, with Republicans making major gains across the country. In West Virginia, the high tide of 1936 was reduced by 100,000 votes, although Bob Ramsay was the only Democratic congressman to lose his seat, most of the others saw their margins drastically reduced. A coalition of conservative Democrats and Republicans would make their presence felt in both the House of Representatives and the United States Senate. No longer would Franklin Roosevelt enjoy such subservient legislative bodies.

The proof of the pudding, as they say, is in the tasting. Evidence of the unpopularity of the Hull trade policies in West Virginia was Senator Matthew M. Neely having voted in favor, only to oppose the treaty a second time. Especially true for the Democrats in West Virginia, it was fair to say no other special interest or voting bloc received as much consideration, especially in an election year, as did labor. Both heads of the major unions, John L. Lewis of the CIO and William Green of the AFL, wielded considerable influence in West Virginia’s politics.

Like Bob Ramsay, “Andy” Schiffler had at one time been a prosecuting attorney. For six years, Ramsay and Schiffler would fight pitched battles over the right to represent West Virginia’s First Congressional District in the House of Representatives. The all-consuming desire to remain in government has been referred to as “Potomac Fever” and if so, Bob Ramsay had a near-terminal case of it.

The 1940 election was quite different in at least one respect; it was a presidential election year. At the top of the Democratic ticket was the best-vote-getter the party had: Franklin Delano Roosevelt. FDR remained highly popular in West Virginia and former Congressman Robert L. Ramsay was anxious to win back his seat in the House. Ramsay sought a rematch with A. C. Schiffler in 1940, but his standing inside his own party did not prevent another serious Democrat from challenging him for the nomination. C. Lee Spillers of Wheeling, a prosecuting attorney, sought to move up to the House. Ramsay was renominated and the differences between the former congressman and the incumbent were like night and day. A.C. Schiffler introduced a bill that would have banned all immigration to the United States until further notice. Bob Ramsay was, of course, an immigrant himself.

In a bitter and hard-fought campaign, with Roosevelt and Matthew Neely at the top of the ticket, Robert L. Ramsay managed to beat Congressman A.C. Schiffler and take back his seat in the House. Schiffler had been popular, especially inside his own Republican Party, and kept up his political contacts after returning home to West Virginia. It soon became readily apparent he would run again in 1942.

In their final grudge match, A.C. Schiffler reversed his 1940 defeat and beat Congressman Ramsay decisively. Out of office once again, former Congressman Bob Ramsay found shelter in the New Deal he had steadfastly supported throughout his time in the House of Representatives. Leaving Congress in 1943, he remained in Washington, D.C., working as a special assistant to the attorney general of the United States. Doubtless, Ramsay would have sought yet another rematch with Andrew Schiffler in 1944 had it not been for Matthew Neely. Neely, finishing out a term as governor of West Virginia, found private life even more distasteful than Bob Ramsay. With no Senate seat open and barred from a second consecutive term as governor, Neely ran for the only office available to him: the House of Representatives. The old Democratic warhorse managed to beat Congressman A.C. Schiffler, but only barely. Neely, who had represented the First District in the House of Representatives years before, was without question the strongest candidate the Democrats could have fielded against Andy Schiffler. With Franklin Roosevelt once again atop the Democratic ticket, Neely only managed to nudge Schiffler out of office by 950 votes.

Realizing all too well his inability to beat the Colossus of West Virginia politics, Bob Ramsay did not run against Neely for Congress in 1944. Thinking the route back to the House was closed to him for a period of years, Ramsay opted to return to West Virginia where he worked as an assistant to the state attorney general. Ramsay’s political career was both stalled and revived when Matthew M. Neely was unexpectedly defeated for reelection in 1946 by Republican Francis J. Love. Ironically, A. C. Schiffler almost certainly would have run a stronger race and could have served yet another term in Congress, but the former congressman chose not to be a candidate, preferring to return to his law practice. The 1946 election was the best for Republicans nationally since 1928 and they won control of both houses of Congress.

With Matthew Neely off and running to reclaim his former seat in the U.S. Senate in 1948, 71-year-old Robert Ramsay ran in the Democratic primary for West Virginia’s First Congressional District. Ramsay faced five opponents in the primary and won with just over 31% of the vote. Ramsay managed to beat Congressman Love as 1948 was as good a year for Democrats as 1946 had been for Republicans. Love was not an especially strong candidate and Bob Ramsay won easily. There were signs his popularity inside his congressional district was diminishing. Ramsay faced a primary opponent in 1950 who won a third of the vote. In a rematch with Francis Love, Ramsay won a narrow victory. It was the last victory of Bob Ramsay’s long political career.

In 1952, Senator Matthew Neely sponsored his protégé Robert Mollahan, who beat Ramsay in the Democratic primary. Ramsay, 77 years old, tried again in 1954 and was humiliated. Working as an assistant prosecutor in a county office, Ramsay tried to unseat his former boss in the primary in 1956 and lost yet again. That November, Robert Ramsay died. © 2024 Ray Hill