By Ray Hill

Howard Baker had accomplished what most observers had believed to be the impossible by defeating Governor Frank Clement for the United States Senate in the November election in 1966. Baker became the first Republican ever to be popularly elected to the U. S. Senate since Tennesseans began electing senators in 1916. It had taken Republicans fifty years to finally elect one of their own to the United States Senate.

Nationally, Republicans had made substantial gains in the off-year elections. The GOP picked up three seats in the United States Senate. Howard Baker won the seat held by Senator Ross Bass in Tennessee; Governor Mark Hatfield won the Senate seat of retiring Senator Maurine Neuberger in Oregon and Senator Paul H. Douglas of Illinois had been defeated for reelection by challenger Charles Percy.

Almost immediately, Baker attracted attention by the national press. Columnist Holmes Alexander wrote a column in March of 1967 headlined, “Howard Baker Is Making His Mark as a Senator.”

Alexander pointed out, like the late President Kennedy, Baker had been a PT boat commander during World War II and the youthful-looking forty-one year old Tennessean had recently made his “maiden” speech on the floor of the Senate.

The topic of Senator Baker’s speech was tax sharing with the states, a subject Alexander described as the “quaint and curious lore known as political economics.”

When Howard Baker stood up to make his maiden speech on the Senate floor, there were revenue sharing bills introduced by Democratic Senators Ernest “Fritz” Hollings of South Carolina and Joseph Tydings of Maryland, as well as competing versions introduced by Republicans Jacob Javits of New York and Hugh Scott of Pennsylvania. Senator Javits, Alexander noted, had six co-sponsors while Senator Scott’s bill had five co-sponsors. When Howard Baker introduced his “Tax Sharing Act of 1967”, he brought along fifteen co-sponsors.

Holmes Alexander credited Baker and his staff with shrewd and careful deliberation prior to introducing the Tax Sharing Act of 1967. Alexander explained Baker’s success by pointing out, “They canvassed every Senator and every Senator’s administrative assistant in whipping up support.”

The columnist also believed Baker’s early success had much to do with the Tennessean’s approach in writing a bill that was “modest in what it asks, simple of execution and very well researched.”

Alexander concluded his column by noting, “Not many beginners dare to launch Senate careers on a non-glamorous subject which brings little personal publicity, even though it could mean much benefit to the nation and the sponsoring party.”

“This kind of legislative aggression,” Alexander wrote, “takes a certain kind of nerve and savvy with which young Mr. Baker appears to be loaded.”

Despite being a freshman senator of the minority party, Howard Baker proved to be a popular speaker for his party. When he returned to Nashville in September of 1967 to speak before a gathering of Republican women, Senator Baker mentioned he had already traveled to twenty-six states. Baker’s message was quite simple; he believed a Republican would win the presidency in 1968 due to Lyndon Johnson’s administration having become a “reactionary and complacent guardian of the status quo.” Howard Baker told the Republican women his travels had allowed him to meet people all across the country in all walks of life and he had found widespread discontent with the Johnson administration.

“Since Democrats have been in the White House,” Baker said, “there has been a vast growth in the number of U. S. troops in Vietnam, a leadership gap has developed, the budget has increased by $90 billion to $175 billion, and the strength of NATO has drastically declined.”

Senator Baker had traveled to New Orleans just after being sworn into office to speak to the National Federation of Republican Women. Later that January Baker went to New York to speak to yet another group of Republican women.

While Senator Baker’s heavy travel schedule had him visiting other states on behalf of the GOP, he did not neglect Tennessee. When the new Anderson County courthouse was dedicated in May of 1967, Howard Baker made the featured speech and was joined by Second District Congressman John J. Duncan.

Ellis Binkley, the political editor of the Kingsport Times-News, wrote a column that detailed Howard Baker’s heavy schedule, but the senator proudly noted he had missed only three recorded votes in the Senate and still managed to be in Tennessee “about once a week.”

Senator Baker did admit to Binkley that he was “plumb tuckered out” and intended to remain for a few days at home and simply rest.

Baker along with Congressman Bill Brock of Chattanooga, helped to foster Republican opposition to entrenched Democrats all across Tennessee. Claude K. Robertson, a Knoxville attorney, became the new State Chairman of the Tennessee Republican Party in 1967. In his speech to the Republican Executive Committee, Robertson called for an end of the “leap frog” government of Frank Clement and Buford Ellington, which had existed in Tennessee since 1953.

Robertson proposed to do that by “putting forth able and imaginative candidacies at all levels of government.”

The new state chairman outlined an ambitious agenda for the Tennessee GOP, which included taking control of the State House of Representatives, elect at least one more congressman, carry the Volunteer State for the Republican presidential nominee in 1968 and elect a Republican governor and U. S. senator in 1970.

Astonishingly, every goal in Robertson’s agenda was met, save for electing another Republican congressman, by 1971. Tennessee Republicans, with the help of Knoxville’s own Robert “Bob” Booker, would briefly take control of the State House of Representatives and elect Bill Jenkins Speaker. Richard Nixon carried Tennessee in 1968 over Hubert Humphrey and George Wallace; Bill Brock would defeat Senator Albert Gore for reelection in 1970 and Winfield Dunn would become the first Republican to be elected governor of Tennessee since 1920. Republicans already held four of Tennessee’s nine congressional seats when Dan Kuykendall of Memphis was elected in 1966 the same year Howard Baker had defeated Frank Clement.

That summer Senator Baker spoke, along with Senator Gore, at the dedication of the Howard H. Baker, Sr. Lake near Oneida. It had to give the senator much personal satisfaction to see the lake named for his late father.

Howard Baker was already being discussed as a presidential possibility, at least in Tennessee. Some Republicans wanted Baker to be Tennessee’s “favorite son” candidate at the 1968 Republican National Convention. Baker did not discourage the idea and even suggested that at least a sixth of the Tennessee delegates and alternates to the convention should be Negroes. The Tennessee delegation to the 1964 Republican National Convention had been all-white and Baker’s suggestion was hardly welcome to some former Democrats who had become Republicans, yet remained segregationists.

George Lee, long prominent in Tennessee’s Republican Party, was black and had been denied a seat the 1964 GOP National Convention. Lee had refused to support nominee Barry Goldwater, yet had enthusiastically backed Howard Baker in both his 1964 and 1966 Senate bids. Howard Baker felt strongly Republicans should be inclusive and worried about some of the GOP party apparatus having been seized by former Democrats who were segregationists.

Even in Tennessee Howard Baker’s prospective presidential candidacy was not universally hailed. Many Republicans affiliated with Chattanooga Congressman Bill Brock were looking to support former Vice President Richard Nixon. Some Nashville Republicans were enthused about another candidate who had been elected in 1966: California Governor Ronald Reagan.

In November of 1967, Senator Howard Baker was “unhappy” with the votes cast by some Democrats inside Tennessee’s Congressional delegation on the compromise of the congressional redistricting bill. Baker declared the measure was aimed at delaying the “one man, one vote” ruling of the U. S. Supreme Court. Senator Baker flatly stated he did not believe the compromise was constitutional and called for its defeat inside the Senate. The compromise had been passed in the House of Representatives 241 – 105. Five out of nine Tennessee congressmen had voted against the compromise bill, including every Republican. Jimmy Quillen, John J. Duncan, Bill Brock, and Dan Kuykendall had all voted against the legislation. The sole Democrat in the Tennessee Congressional delegation to vote against the compromise measure was Robert “Fats” Everett, a conservative West Tennessean. Democrats Joe L. Evins, Richard Fulton, William Anderson and Ray Blanton had voted for the bill.

Senator Baker said the vote inside the House was proof of a growing opposition to the legislation that was bipartisan. Baker said the bill was nothing more than “an attempt to delay fair redistricting of congressional seats for five years.”

Howard Baker’s opposition to the compromise bill was at variance with the position taken by his father-in-law, Senate Minority Leader Everett Dirksen, who had consistently bitterly fought to delay the “one man, one vote” dictate.

Baker’s growing national reputation continued to grow when his office announced he would be meeting with former president Dwight D. Eisenhower that summer. The topic of conversation between Senator Baker and Ike was nuclear powered “desalting” plants, which would help provide much needed water for the Middle East.

While Republicans in Tennessee had been elated by Howard Baker’s election in 1966, they were also thrilled by having elected yet another congressman, as well as forty-one members of the legislature. As Republicans proposed to build upon their gains in the next election, Tennessee Democrats also pondered the future.

Former U. S. senator Ross Bass mulled his defeat at the hands of Governor Frank Clement and let it be known he was considering running another statewide campaign. Bass told friends he might challenge Baker for reelection in 1972 or perhaps enter the Democratic primary for governor in 1970. Despite the Republican gains in 1966, Tennessee Democrats showed no hesitation in fractious infighting and it was becoming clear that the 1970 gubernatorial primary would be hard fought. Frank Clement seemed to be a looming possibility and it was all but certain John Jay Hooker would run again.

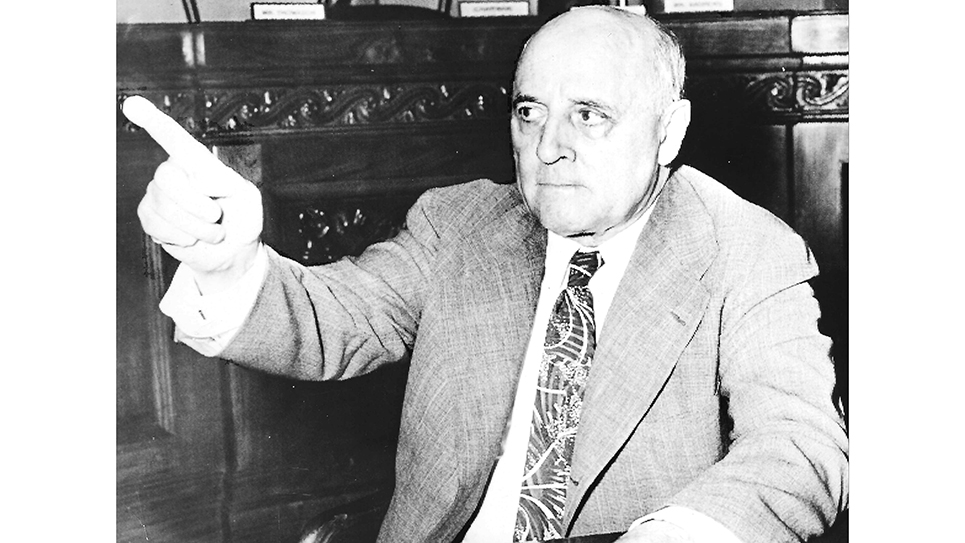

Following his defeat in the 1966 Democratic primary, Bass had settled into his own consulting firm, which was merely another name for his having become a lobbyist. Bass had been touted as considering another run for Congress, a rumor the former senator quickly squelched. “I have absolutely no desire whatever to run for the House,” Bass snapped.

“If my health is still good in 1972, I’ll certainly give serious consideration to returning to the Senate, and I will not rule out the possibility of running for governor in 1970,” Bass said.

Ross Bass believed had he been renominated in 1966, he would have gone on to win the general election against Howard Baker. Former governor Frank Clement was reputedly being considered for some appointment from the Johnson administration, perhaps as an ambassador to a South American country.

Even though Howard Baker had barely finished his first year in the United States Senate, the political pot continued to boil in Tennessee.