Tarheel Statesman: Cameron Morrison of North Carolina

By Ray Hill

Since 1900, only three men have served as a congressman, governor and United States senator from North Carolina: Cameron Morrison, Clyde Hoey and William B. Umstead. Only Clyde Hoey was elected to all three offices, while Morrison and Umstead were both appointed to complete unexpired terms in the U.S. Senate.

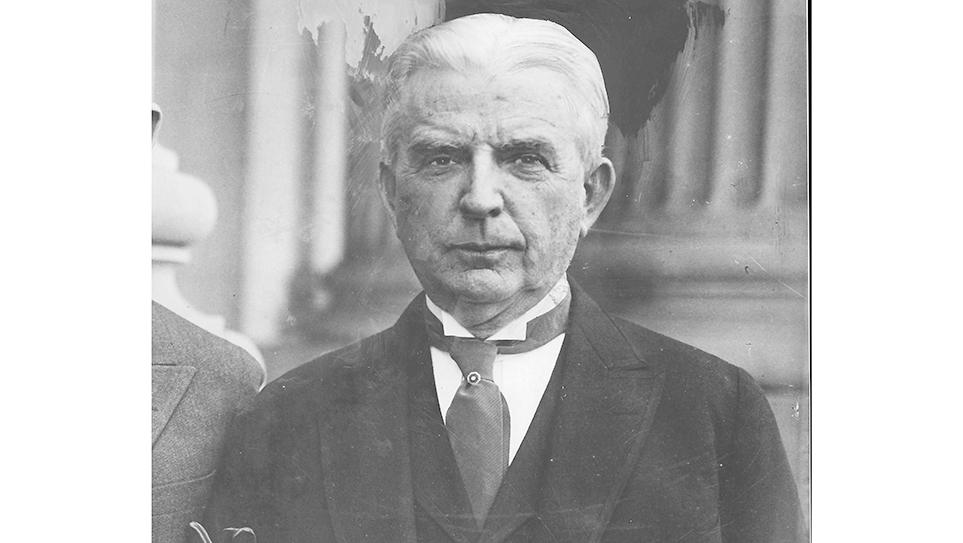

Morrison was acknowledged to be one of North Carolina’s best governors. A man of distinguished appearance, Cameron Morrison looked like an aristocrat and dressed the part, although his beginnings were relatively humble. Morrison chewed tobacco and spit it as well. During his time as governor of North Carolina, Morrison was a widower and his 10-year-old daughter served as his official hostess. A dynamic man who was forthright in the positions he took, Morrison was described by one political opponent as “a man chuck full of courage.” Oftentimes dressed in a shirt with a “bat-wing” collar, Cameron Morrison was a colorful character even during his own time.

Cameron Morrison began his career as part of the movement that swept North Carolina and was led by Furnifold M. Simmons to restore the power of the Democratic Party inside the Tarheel State. A combination of Populists and Republicans had won control of the state legislature and elected one of their own to both of North Carolina’s seats in the United States Senate. Morrison lost a bid for the state Senate before winning an election to serve in that body; Morrison helped to elect F. M. Simmons to the latter’s first term in the U.S. Senate in 1901. In 1902, Morrison campaigned for the Democratic nomination to represent Charlotte in the U.S. House of Representatives, but he was defeated.

Having only served a term in the state Senate, Cameron Morrison began a campaign for governor in 1920. F. M. Simmons had not forgotten Morrison’s support and the senator was by that time the boss of North Carolina’s Democratic Party. Cameron Morrison was the candidate of the Simmons Democrats in the primary. Morrison had announced his candidacy two years before the 1920 Democratic primary and had been endorsed by Senator Simmons in 1919. Morrison was hampered in that election by the death of his wife and it took some months for the grieving candidate to get his campaign back on track. Morrison led the pack of candidates by a mere 87 votes and his nearest competitor, Lieutenant Governor O. Max Gardner, immediately called for a run-off election. Both candidates charged the other with being the candidate of a political machine. Morrison denounced Gardner as the candidate of the “Shelby Dynasty” line of governors. Gardner replied that Morrison was the candidate of the Simmons machine. Cameron Morrison ran as the more conservative of the two candidates and won the run-off primary.

Once he was installed as governor, Morrison accumulated a rather progressive record. Governor Morrison was the chief and loudest advocate for “good roads” in North Carolina against stiff opposition at the time. Morrison argued good roads would not only be a benefit to citizens but also would help to attract businesses to the state which would in turn provide good-paying jobs for residents. Governor Morrison managed to muscle a $50 million bond issue through North Carolina’s state legislature. Two years later, Morrison induced the legislature to appropriate another $15 million for the road-building program.

The governor sought and secured $20 million to improve funding for North Carolina’s universities, as well as the state-run schools for the hearing and visually impaired. Morrison sought more aid for the mentally ill and better funding for the North Carolina Board of Health. Governor Morrison also pushed the legislature to significantly increase funding for schools in the Tarheel State.

As governor, Morrison pushed the state Board of Education to pledge no form of evolution would be taught in North Carolina’s public schools. “I do not believe that man, God’s highest creation, is descended from a monkey,” Governor Morrison said. “I will not consent that any such doctrine or any intimation of such a doctrine shall be taught in our public schools.”

Cameron Morrison was still serving as governor when he had married Sarah Watts in Durham. Mrs. Watts was the widow of George Washington Watts. George W. Watts had been the business partner of the Duke brothers for 43 years. Together, George W. Watts and the Duke brothers merged their company with four other tobacco concerns to form the American Tobacco Company. The company had a virtual monopoly and stranglehold on the tobacco business in the United States until it was disbanded by a decision from the U.S. Supreme Court. Watts and the Dukes invested in other businesses, including textiles. The partnership of George Watts and the Duke brothers only ended with the death of Watts in 1921. Watts’ estate was valued at approximately $184 million in today’s dollars.

Cameron Morrison’s marriage to Sarah Watts made him a very wealthy man. At the end of his governorship, the former governor and his bride settled into an opulent home, Morrocroft, in Charlotte. Morrison turned the 3,000-plus acres surrounding Morrocroft into a working farm that produced an income of around $2.5 million in today’s dollars.

The bitterness of the 1920 gubernatorial primary had faded and been forgotten between Morrison and O. Max Gardner. Gardner had been elected governor in 1928. That same year, Senator Furnifold M. Simmons had bolted the Democratic Party by openly refusing to vote for the Democratic presidential nominee, Alfred E. Smith. North Carolina voted for Republican Herbert Hoover. Senator Simmons had resigned his place as North Carolina’s Democratic National Committeeman following his refusal to support Smith. Cameron Morris was elected to fill the post.

Morrison helped heal the breach between him and O. Max Gardner by liberally contributing to the latter’s campaign kitty in 1928. Likewise, Morrison financially contributed to Josiah W. Bailey’s successful bid to defeat Senator Simmons in the 1930 Democratic primary.

When Senator Lee Slater Overman died on December 22, 1930, with two years left on his term of office, it fell to Governor O. Max Gardner to appoint a successor to hold the seat until the 1932 election. Speculation fell on a number of possibilities, but most press reports seemed to believe former Governor Cameron Morrison was the likely beneficiary. Morrison remained popular for his road-building program, which TIME magazine called “the best hard-surfaced road system in the South.”

With the appointment to the United States Senate, Cameron Morrison inherited a stinging political problem with the pending nomination of Frank R. McNinch, who had been nominated by President Hoover to serve on the Federal Power Commission. McNinch, a former mayor of Charlotte, was a “Hoovercrat”— a Democrat who supported the presidential candidacy of Herbert Hoover. Many staunch Democrats who had gone down the line for the Democratic ticket and had supported Al Smith for the presidency were deeply opposed to the McNinch nomination. Senator Morrison opted to support his fellow townsman, which earned him the enmity of a goodly number of folks inside his own party.

Morrison had the support of Governor Gardner and Senator Josiah W. Bailey as he began his campaign for a full six-year term in the U.S. Senate in 1932. None of his opponents in the Democratic primary appeared to be a real threat. Robert Rice Reynolds was something of a ne’r-do-well and had been often married and, despite being a frequent candidate, had only been elected to no office higher than county attorney. Reynolds finally found his stride with a talent for public speaking and lampooning the wealth of Senator Morrison.

Later known as “Buncombe Bob,” Reynolds’ 1932 Senate campaign became the stuff of legends. Reynolds carried a carpet under his arm as he appeared in rural counties throughout the state, traveling from one destination to the next in an old Ford. Reynolds on the stump detailed Senator Cameron Morrison being chauffeured in a Rolls-Royce to Washington’s elegant Mayflower Hotel, where he lived while in the Capitol. Brandishing the red carpet, Reynolds cried to his audiences, “Cam’s footman takes this here roll of carpet like this. . .” Demonstrating with a whip of his hands, the red carpet being ceremoniously laid so that the senator could walk across it. Bob Reynolds mimicked Morrison strutting across the carpet. “And do you know what he eats in that there hotel?” Reynolds asked his audience. “He eats caw-vee-yah! Do you folks know what caw-vee-yah is? Why that’s fish eggs! Fish eggs from Rooshia!” Reynolds then proceeded to read the breakfast, lunch and dinner menus, as well as the price of each dish, intimating that Cameron Morrison consumed the entire menu daily during a time when many people barely had enough to eat.

The shrewd Bob Reynolds campaigned favoring repeal of the prohibition amendment. Cameron Morrison had cried, “I’m willing to die politically for Prohibition!” Reynolds was helped when the 1932 Democratic National Convention went on record as favoring repeal of the prohibition amendment to the Constitution. What Cameron Morrison likely thought was a lifetime seat in the United States Senate turned out to be a brief sojourn. Bob Reynolds won the run-off election in a landslide.

A decade later, Cameron Morrison revived his dormant political career when he sought election to North Carolina’s newly carved out Tenth Congressional District following redistricting. The 73-year-old former governor dispatched an opponent inside the Democratic primary easily and faced former GOP congressman Charles A. Jonas in the general election. Cameron Morrison won 55% of the vote to return to Capitol Hill. Morrison could likely have served several terms in the House of Representatives had he chosen to seek reelection but the congressman was determined to win back his old seat in the U.S. Senate. Bob Reynolds was retiring in 1944 and Morrison became a candidate for the Democratic nomination. Morrison faced one of North Carolina’s most popular office holders in Clyde R. Hoey, the brother-in-law of O. Max Gardner, and a former congressman and governor. Hoey won the Democratic nomination in a five-man race with almost 69% of the votes cast. Morrison ran a very distant second with just over 26%. It was the end of Cameron Morrison’s electoral career.

Morrison settled into a pleasant life as an elder statesman and country squire. The former governor’s last notable political act occurred at the 1952 Democratic National Convention in Chicago. Many Southern delegates had bolted the 1948 convention over the civil rights platform and walked out. Liberal Democrats provoked a fight in 1952 by proposing every delegate to the convention be required to sign a loyalty pledge to back the presidential nominee selected by that same convention. U.S. Senator Blair Moody of Michigan offered a resolution that would deny delegates a seat in the 1952 Democratic National Convention should they refuse to sign the pledge. Morrison spoke out against the Moody resolution. The former governor said he was likely the oldest delegate attending the convention, noting he would be “83 in a few days and a lifelong Democrat.” Morrison was still a fire-eater of a speaker and thundered in conclusion, “My God, deliver me from such tyranny as this over the minds and hearts of the Democrats of this country.”

As Democrats sought to beat back the Eisenhower – Nixon ticket in the South, the “Squire of Morrocroft” spoke without hesitation for presidential nominee Adlai Stevenson. While in his eighties, a friend asked the former governor if he intended to write his memoirs. A dark frown covered Morrison’s face before he said, “Not until after I retire.”

The “grand old patriarch of North Carolina politics” went on a trip by automobile to Canada with his grandson James J. Harris Jr. and a friend from Charlotte. The 83-year-old Morrison was in Quebec when he suffered a heart attack. The younger Harris reported to his father Morrison was feeling uncharacteristically unwell and decided to remain in bed in his hotel room. The following day, Cameron Morrison had a heart attack around noon and died. © 2024 Ray Hill