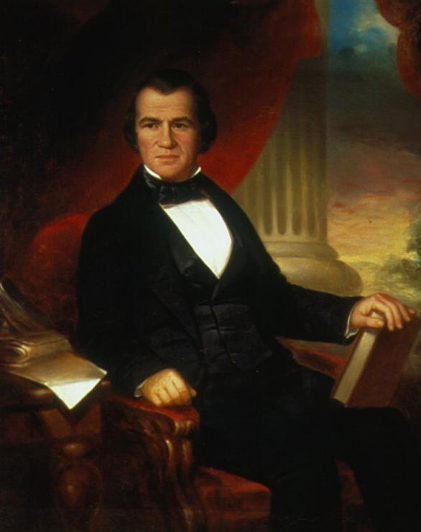

Only nine men have made the transition from governor of Tennessee to United States senator. One of those nine was one of the most successful politicians to take part in Tennessee’s turbulent politics: Andrew Johnson. In fact, Andrew Johnson prospered politically during the Civil War, the most tempestuous time in Tennessee’s history. Johnson’s political rise was sure and steady and eventually he became President of the United States. Despite rising to the pinnacle of political success, it was an exceedingly bitter experience for Andrew Johnson.

In many respects, the life of Andrew Johnson was the very definition of an American success story. Johnson was born in abject poverty in Raleigh, North Carolina, into a home that was less home than hovel. Both of Johnson’s parents had worked at one time as servants in a tavern and neither could read nor write. Andrew Johnson never attended any kind of school and was illiterate. Johnson was only three years old when his father Jacob died of what was likely a heart attack while ringing the town bell for help. The elder Johnson had just rescued three men who had been drowning. Johnson’s mother, Polly Johnson, became a washerwoman to support her family, which was then considered something less than a lowly occupation. Polly did eventually remarry, but she married another poor man, which did little or nothing to improve the material circumstances of her family. Good fortune did finally shine on Andrew Johnson when Polly apprenticed him to a local tailor. The agreement, which was legally binding, apprenticed the ten year-old Johnson to the tailor until he was twenty-one. There was another benefit to working in the tailor’s shop as some folks dropped by to read aloud while the tailors worked. Even before becoming a tailor’s apprentice, Andrew Johnson would visit the tailor shop to listen to the readers. Eventually, Johnson acquired some elementary reading skills, but he was unhappy as a tailor’s apprentice. Along with his brother William, who had been apprenticed to the tailor before Andrew, the brothers ran away. The tailor promptly offered a reward for both boys, but especially wanted Andrew Johnson back in his shop. Johnson offered to buy out his way out of his apprenticeship, but the tailor would not agree. Andrew Johnson decided to go west and traveled to Tennessee, the most of his journey made on foot. For a fleeting time, Johnson lived in Knoxville, but left for Mooresville, Alabama before moving to Columbia, Tennessee. Johnson returned to get his mother and stepfather, both of whom were eager to move west as well. The Johnsons settled in Greeneville, Tennessee. If Andrew Johnson had been touched by wanderlust before, his soul was soothed by Greeneville, which he loved. Johnson set up a tailor’s shop in Greeneville, which visitors can still visit to this day. When he was eighteen, Johnson married sixteen year-old Eliza McCardle, daughter of the local shoemaker. Their marriage would last almost fifty years and produce five children. Eliza Johnson disliked attention and would remain in Greeneville throughout most of her husband’s political career. Even when Johnson succeeded Abraham Lincoln as president, Eliza preferred her home in Greeneville to the White House. The Johnson’s eldest daughter Martha would serve as the President’s official hostess during his time in the White House. Yet Eliza’s influence upon her husband could hardly be overestimated. It was Eliza who spent hours tutoring her ill-educated husband.

Andrew Johnson’s political career began literally at the bottom of the rung, when he was elected town alderman. While he may have been illiterate for years, politics afforded Andrew Johnson the opportunity to speak publicly and he excelled at the endeavor. Johnson was not merely an able speaker, but a gifted orator with the power to both entertain and move his audiences. Johnson moved up the political ladder, quickly winning election to the Tennessee House of Representatives. It was in the legislature where Andrew Johnson won a reputation for bucking his own party. Johnson was a Democrat and highly admired the most notable Democrat of them all: Andrew Jackson. Still, Andrew Johnson did not feel duty bound to vote with his party, revealing an independent streak, which remained with him throughout his life. Johnson was a man of firm convictions and could be infuriatingly stubborn.

Johnson suffered a rare defeat in 1837 when he sought reelection to the state legislature. Andrew Johnson ran again in 1839 and was elected. Johnson was careful to mend his political fences and built a powerful political organization in Greene County.

Nor did Andrew Johnson’s political talents go unnoticed by his fellow Democrats. Noting that crowds flocked to hear Johnson speak, Tennessee Democrats selected him as a presidential elector in the 1840 election. Andrew Johnson, supporting President Martin Van Buren, campaigned the length and breadth of Tennessee, urging his fellow Tennesseans to vote for Van Buren. The Whig candidate, General William Henry Harrison, won Tennessee decisively, although Johnson gained significant exposure from his canvass throughout the state. Johnson won a political promotion in 1841 when he was elected to the Tennessee State Senate.

As Johnson began his political rise, he had also moved up in the world in terms of business success. Johnson’s tailoring shop prospered; in fact, Johnson was himself something of a walking advertisement for his own skills. Andrew Johnson was always impeccably dressed for any public appearance, a habit he kept for the rest of his life. Along with his business, Johnson acquired real estate holdings, built a fine home in Greeneville and purchased a farm where he settled his mother and stepfather. Johnson also owned several slaves.

The lure of politics was a siren’s call he could not resist and Andrew Johnson sold his tailoring business so he could immerse himself in electioneering. The next logical step in his political progression was a seat in Congress. In 1843, Johnson won a seat in the U. S. House of Representatives. One of the themes of Johnson’s political career was his advocacy for the less fortunate, likely a topic he personally felt keenly about, especially considering his own childhood. Andrew Johnson was always ready to fight for the poor as opposed to what he derided as “the aristocracy.” Johnson served five terms in Congress and while he supported fellow Tennessean James K. Polk when the president went to war with Mexico, it did not mean the two enjoyed warm personal or political relations.

Polk noticed Congressman Andrew Johnson in attendance at a White House function just before the president relinquished his office to General Zachary Taylor in 1849. Polk wrote in his dairy that while Johnson professed to be a Democrat “he has been politically, if not personally hostile to me during my whole term.” Polk believed Johnson to be “vindictive and perverse in his temper and conduct.” The President complained Johnson did not have “the manliness and independence” to openly declare his profound opposition to the Polk administration because “he knows he could not be elected by his constituents.” Considering that Polk had been twice beaten for governor by a Whig candidate and that Tennessee had voted for Whig presidential candidates in the elections of 1840, 1844, 1848 and 1852, it might well have been wishful thinking on the part of the president. Polk had lost his home state in the 1844 presidential campaign to Henry Clay of Kentucky. Polk closed the entry in his diary by carefully noting, “I am not aware that I have ever given him cause for offense.”

Andrew Johnson may well not have been an orthodox Democrat, but he certainly showed a broad streak of populism. Congressman Johnson pressed for the popular election of United States senators, as well limiting federal judges to a term of twelve years on the bench. When Johnson sought his last term in Congress, the Whigs offered no opposition, nor did they have to, as renegade Democrats nominated a candidate to oppose the congressman so deep was the divide inside the Democratic Party. Democrats were divided on several issues, but none so hotly as the issue of slavery.

Evidently the only way to defeat Andrew Johnson was gerrymandering his Congressional district. When the Whigs won a majority in the legislature, they did precisely that. Johnson was too astute a politician not to realize he could not win in his own district. The congressman felt his political career was at an end. Some of his friends began promoting him for the Democratic nomination for governor. Doubtless some Democrats who thought little of Johnson saw no harm in giving him the gubernatorial nomination; after all, the Whigs had successfully elected the governor in the previous two elections. The Democratic state convention unanimously nominated Andrew Johnson while the Whigs nominated Gustavus Henry, the man who had been primarily responsible for redrawing the lines of Johnson’s Congressional district. The two men conducted a joint campaign, speaking at courthouses all across Tennessee. Andrew Johnson surprised not only most of the Whigs, but some Democrats as well when he narrowly defeated Henry. Governor Johnson had little real power as Tennessee’s chief executive, but he used every advantage he had shrewdly. With the legislature still in the hands of the Whigs, Johnson traded with powerful Whig legislators to approve some of his own appointments in exchange for the governor appointing John Bell to the U. S. Senate. Few believed Johnson could be reelected governor in 1855, but after a bitter campaign, he won a second term, albeit by a slender margin.

Andrew Johnson did not seek a third term as governor as he was already looking to Washington and a seat in the United States Senate, a prospect that horrified Whigs in Tennessee. Whigs campaigned hard to win a majority in the legislature precisely to keep Johnson from being elected to the Senate. Governor Johnson campaigned equally hard for the Democratic nominee in the gubernatorial election, as well as Democratic candidates for the state legislature. Democrats elected Isham G. Harris governor and won a majority in the legislature. Governor Johnson gave his farewell address as Tennessee’s chief executive and two days later, the Tennessee legislature elected him to the United States Senate.

Johnson did not appeal to the “Bourbon” Democrats in Tennessee, the well-heeled attorneys and plantation owners, but few Democrats were more popular with the working class voters and small businessmen. Andrew Johnson had repeatedly demonstrated his ability to win elections, even when the odds were stacked against him. Johnson’s iron constitution helped him to remain a favorite with voters, as he endured difficult travel over bad roads and other deprivations and hardships to see as many people as possible. Few people, especially those working people, forgot meeting Andrew Johnson. They also never failed to remember him at the polls.

When Andrew Johnson arrived in Washington, D.C. as Tennessee’s junior senator, he came alone, as Eliza insisted upon remaining at their home in Greeneville. Mrs. Johnson would visit the Capitol only once during Johnson’s first term in the Senate. The country was becoming more polarized as the slavery issue tore asunder old alliances and made bitter enemies of former friends. The political atmosphere in Washington and the country was becoming increasing toxic. Tennessee became a microcosm of the country, tearing itself apart over the slavery issue.

Andrew Johnson quickly chose a side.