William Gannaway Brownlow, better known to Tennesseans as “Parson” Brownlow, was another Volunteer State governor who made it to the United States Senate. Brownlow was as colorful a character, perhaps even more so, than his predecessor, Andrew Johnson. By trade, Brownlow was a journalist, minister of the cloth, and politician. Orphaned at the age of eleven and despite having little formal education, William G. Brownlow drifted into the ministry, becoming a traveling minister for the Methodist Church. Brownlow brought a fierce passion to his work and he set out not only to save souls, but people from the temptation to join another denomination.

Once Brownlow married, he found it necessary to look for other work to support his family. The Parson had a talent for writing, which naturally drew him to journalism and Brownlow bought a newspaper in Elizabethton, Tennessee, popularly known as Brownlow’s Whig. Brownlow entered the newspaper business as a stern partisan of the Whig Party. Not only did Brownlow champion the Whig Party nationally and locally, he promoted the presidential prospects of Kentucky’s Henry Clay. Brownlow was such a partisan of both the Whig Party and Henry Clay that his son, John, later recalled one of the rare times he witnessed his father cry was due to Clay’s loss of the 1844 presidential election.

Brownlow moved his newspaper from Elizabethton to Jonesboro, then again to Knoxville in 1849. Brownlow’s prowess with a pen made his newspaper influential and before the Civil War erupted, the Parson had almost 15,000 subscribers all across the country.

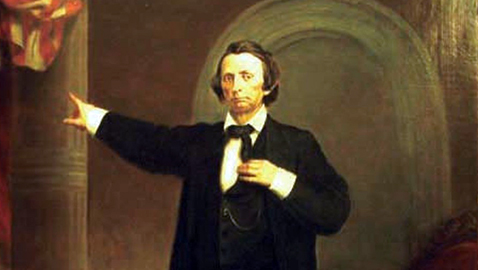

Gaunt and clean-shaven, the Parson’s rather ordinary exterior hid a soul that thrived on controversy. If no controversy existed heretofore, Parson Brownlow would supply it through the pages of his newspaper. Brownlow gloried in attacking his opponents and spared them little. Brownlow’s attacks in print were almost always personal and corrosive in nature. The Parson’s friends and supporters always enjoyed his attack on his adversaries and referred to him as the “Fighting Parson.” Taking pride in his ability to involve himself in any raging controversy, political or social, Brownlow crowed he was never neutral about anything. Brownlow remained an ardent Methodist and any critic of the Methodist faith would feel the lash of the Parson’s pen and tongue. Increasingly, Brownlow became a spokesman for his own point of view, which included adherence to the Methodist Church, support for the Whig Party, and lectures upon the evils of the influence of imbibing alcoholic beverages. Parson Brownlow was a strong proponent of temperance. One of the favorite tactics of Brownlow was to accuse his opponent of being drunkards. Eventually, William G. Brownlow became one of the leading voices in Tennessee against secession. Brownlow was equally opposed to the Confederacy. For decades Brownlow had been a bitter political opponent of Andrew Johnson. The two men frequently opposed one another on the stump, but found themselves allied in their opposition to secession. When Tennesseans voted in February of 1861 in a referendum to secede from the Union, Brownlow joined Andrew Johnson in campaigning hard against secession. Both native East Tennesseans, Brownlow and Johnson helped to convince enough of their neighbors to reject the idea of secession by two-to-one majorities. The February referendum failed and when voters again went to the polls the following June, both Brownlow and Johnson went on speaking tours to oppose it. While East Tennessee continued to oppose secession, Middle and West Tennessee voted heavily to leave the Union.

Once his mind was made up, virtually nobody or anything could change the Parson’s beliefs. For twenty years Brownlow had been a fervent political supporter of John Bell, who had enjoyed a storied political career, serving as Speaker of the U. S. House of Representatives, Secretary of War, and U. S. senator. Bell was urged to run for president in 1860 as a third party candidate against Republican Abraham Lincoln and Democrat Stephen Douglas. Among those urging Bell to run was William G. Brownlow. The Whig Party had disintegrated and delegates went to Baltimore to attend the national convention of the newly formed Constitutional Union Party. Bell competed for the presidential nomination of the Constitutional Union Party with Sam Houston. Bell was finally nominated and Parson Brownlow strongly supported his friend’s presidential candidacy. John Bell carried Tennessee, as well as Kentucky and Virginia.

As Civil War approached, John Bell’s attitude shifted. While Bell still believed in preserving the Union, he also believed if Tennessee were invaded by Union troops, the Volunteer State had every right to protect itself from the invaders. Bell came to Knoxville for a speech, speaking at the courthouse. If Bell thought he might make some converts, he was much mistaken. Noting that many of his long-time friends had absented themselves from his speech, Bell met with several friends after speaking, among them was William G. Brownlow. John Bell gently observed the absence of his friends and the plainspoken Parson replied of course he didn’t attend his friend’s speech and no intention of being present. Brownlow said he did not “wish to witness the spectacle of your being surrounded by your enemies, who a few months ago were denouncing you as a traitor.” Brownlow told Bell, “We did not wish to hear these men shouting for you and see you in such a position.” The Parson then let loose with a “torrent of abuse” against the notion of secession. John Bell remained silent.

The influence of the Knoxville Whig was acknowledged by Brownlow’s enemies, when they tried to back a rival newspaper, the Knoxville Register. J. Austin Sperry, a noisy secessionist was installed as editor of the Register, which touched off an editorial war between the two newspapers. Brownlow gleefully observed the Register had few subscribers and referred to Sperry as a “scoundrel” and “debauchee”, among other things. Nor was it William G. Brownlow’s fiercest feud with a political enemy. Years earlier, Brownlow had engaged in a wild feud with Democrat Landon Carter Haynes, a spat that ended with the Parson assaulting Haynes on a Jonesboro street. Brownlow had beaten Haynes with a sword cane, causing the beleaguered Democrat to pull out a pistol and shoot the Parson in the thigh. Haynes later became the editor of a rival newspaper and the two would trade insults regularly. When he relocated his newspaper to Knoxville, Brownlow casually referred to the competing newspaper, the Standard, as a “filthy lying sheet.”

When Tennessee joined the Confederacy, Parson Brownlow continued to roar his opposition to the Confederate States of America. Initially, Confederate authorities left the Parson alone, but eventually they suppressed his newspaper. Brownlow fled from Knoxville to the Great Smoky Mountains. William G. Brownlow had been far more than political allies; they had been warm personal friends for more than two decades. In fact, Brownlow had named one of his sons after John Bell. In a book he wrote after the beginning of the Civil War, Brownlow readily confessed the break with John Bell had caused him “great pain” and admitted both he and Bell had “parted with tears” that evening. Publicly, Brownlow had despaired his old friend was the “officiating Priest” who was all too ready to sacrifice the country upon the altar of the “false god of Disunion.”

William G. Brownlow negotiated with Confederate officials to turn himself in upon the condition he would not be handed over to local civil authorities, who he insisted were political and personal enemies. Whatever agreement was reached was breached and Brownlow landed in the Knoxville jail.

Brownlow brazenly published his “farewell” in his own newspaper, telling his readers, “This issue of the Whig must necessarily be the last for some time to come…for I am to be indicted for treasonable articles by a Confederate Court in Nashville…I could go free by taking a new oath but my purpose is not to do any such thing.. Leaders of the secession have been trying to have me assassinated all summer…I will not accept bond. I am prepared to die in solitary confinement or at the end of a rope before I will make any humiliating concession to any power on earth.”

Brownlow wrote, “I have committed no offense. I have not shouldered arms. I have discouraged rebellion and I have refused to make war on the government of the United States. That is my offense. I have refused to write false versions of the origin of this war and the breaking up of the best government the world ever knew – – – and all this I will continue to do if it costs me my life.”The fiery Parson explained to his readers, “The real object of my arrest is to destroy the only Union paper left in the 11 seceded states—despite the fact that Southerners advocate freedom of the press.”

Brownlow was charged with treason for the editorials appearing in his newspaper. Brownlow became quite ill with typhoid fever while in Confederate custody and his life was likely saved when he was ordered expelled from the Confederacy. One likely reason Brownlow was freed was because the Confederates had no desire to make a martyr out of the Parson. Northern newspapers noted Brownlow’s incarceration and loudly demanded his release. “Brownlow may be consigned by trembling tyrants to a dungeon but there will be more of God’s sunshine in his soul than can ever visit the eyeballs of his country’s enemies,” one such Northern newspaper thundered. “If a million prayers can avail, the naked stones of his cell will be a softer and sweeter bed than his traitorous foes will enjoy.”

Brownlow, under a flag of truce, was released into the custody of the union, where he met his old enemy, Andrew Johnson in Nashville. Brownlow recovered and began a speaking tour over a six-month period were he spoke in many large Northern cities. Defining his own personal experience as a prisoner made him a celebrity of sorts almost instantly. The Parson also profited personally from his speaking tour and quickly published a book about his experiences. The revenue from his lectures and book allowed him to revive The Whig as he followed Union troops into Knoxville in 1863. Once back in the newspaper business, Brownlow resumed where he left off, railing against the perfidy of the Confederacy. With Union troops occupying most of Tennessee, William G. Brownlow became a candidate for governor in 1865 and was elected, succeeding his old foe Andrew Johnson. Most former Confederates had been disenfranchised and were not able to vote in the gubernatorial election. Johnson quickly became president following the assassination of Abraham Lincoln and the Republican Brownlow had little sympathy for his former ally. Governor Brownlow allied himself with the Reconstruction policies of Congressional Republicans, which were opposed by President Johnson. Brownlow pressed the Tennessee state legislature to ratify the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution, which it did. Governor Brownlow then pressed Congress to fully restore Tennessee to the Union. Brownlow was as successful in pressuring the Congress as he had been with the Tennessee General Assembly. Brownlow’s guiding the legislature and the Congress to fully restore Tennessee to the Union spared the Volunteer State the bitter Reconstruction experience of the other former Confederate states.

Brownlow thought it only proper most former Confederates were disenfranchised at the ballot box, but he also believed in giving former slaves the right to vote, a notion that was incendiary to most Southerners. One unpleasant result of the governor enfranchising former slaves was the birth of the Ku Klux Klan in Tennessee. Parson Brownlow became a fierce critic and bitter opponent of the Klan. Brownlow’s attitude about slavery had changed significantly, as he had once said the institution of slavery had been “ordained by God.” Brownlow boldly debated another clergyman over the slavery issue, but by the time the Civil War began raging, the Parson was fully behind emancipation.

Next week’s column will continue the tale of William G. Brownlow’s path to the United States Senate.