With the sudden death of U. S. senator William Brimage Bate, Tennessee would send someone else to the Senate. Bate had died just days after being sworn-in for his fourth term. Indeed, only two men had ever been elected to serve a fourth term in the United States Senate from Tennessee. Both, William B. Bate and Isham G. Harris, never lived to complete their terms. To this day, only one man has surpassed being elected to four terms in the U.S. Senate from Tennessee.

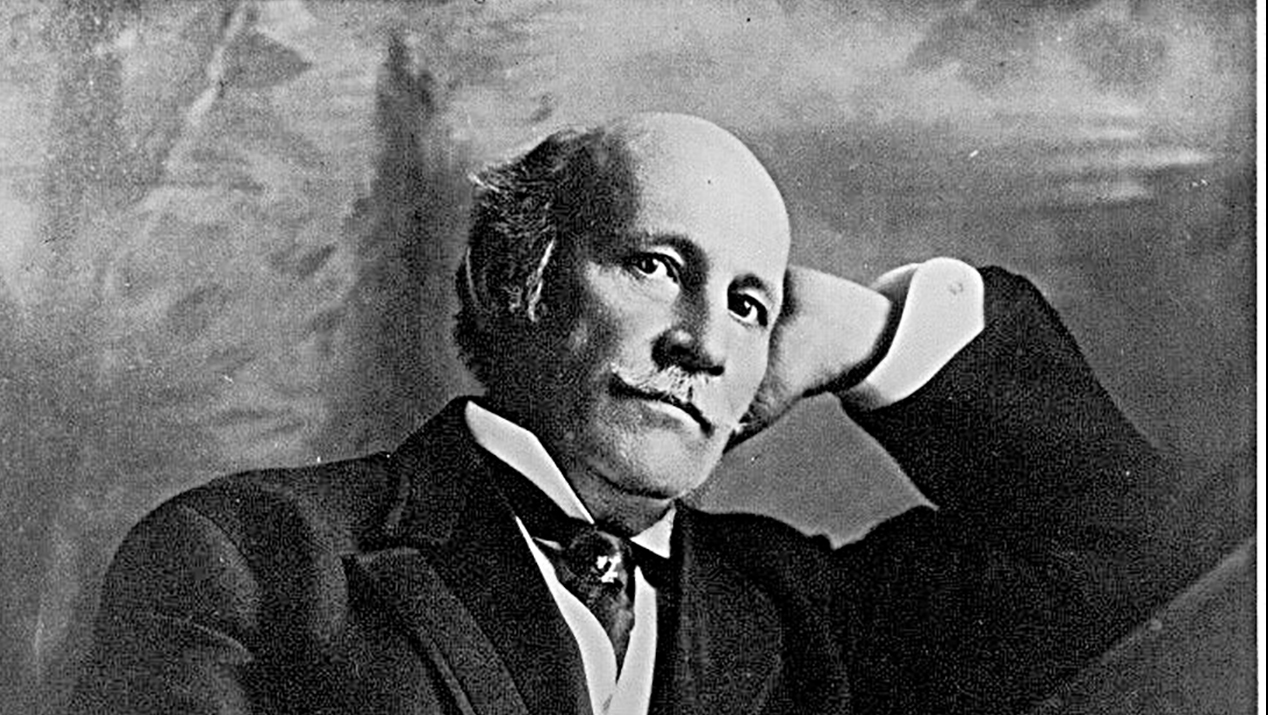

The senatorial contest to serve the remainder of Senator Bate’s term – – – essentially a full term – – – would be held in the Tennessee legislature. It would be more than another decade before Tennesseans would cast ballots to nominate and elect their own U.S. senators. There was no lack of serious contenders, but the race boiled down to three men: Robert Love Taylor, Benton McMillin, and James B. Frazier. Taylor and McMillin had served terms as governor and James Beriah Frazier was the incumbent governor, having just been reelected to another two-year term the previous fall. “Our Bob” Taylor had already amply demonstrated his astounding personal popularity with the voters of Tennessee, having been elected governor three times. Taylor had run for governor once opposed by his brother Alf, who had been the Republican nominee. The gubernatorial contest of 1886 is remembered in Tennessee even today as the “War of the Roses.” Accustomed to the rough and tumble of heated gubernatorial campaigns, voters were mesmerized by the candidates who traveled together all across the state. It was Bob Taylor who suggested both he and his brother were roses, albeit he claimed he was a white rose while Alf was a red rose. From that time forward, supporters of Bob Taylor wore white roses in their lapels, while those backing Alf wore red roses. While the Taylor brothers poked fun at each other, as well the other’s politics, the campaign was free of the usual rancor of political contests. Bob Taylor won the governorship, although Alf would come back decades later to win a term in the governor’s mansion in 1920. After defeating Alf, Bob Taylor won a second term as governor in 1888 rather easily. Taylor was enormously popular with Tennesseans who enjoyed his showmanship, as well as his kindly personality. Kenneth D. McKellar, Tennessee’s longest serving U. S. senator, knew Bob Taylor well and in his book “Tennessee Senators”, opined Taylor was more philosopher than politician and “intensely romantic”, meaning the governor had an idealized outlook on life. McKellar wrote Taylor “knew and cared nothing about money.”

Taylor was vulnerable on one point and was criticized by his opponents for his liberal use of the governor’s pardoning power. Governor Taylor was well known for being unable to resist the compelling story of any mother or wife pleading on behalf of her son or husband. McKellar remembered how he had been both astonished and aghast when his senior law partner insisted he handle a murder case involving a crime of passion. A young man, in a fit of jealous rage had killed another man. McKellar protested he had never tried a criminal case and thought it would be foolhardy for him to attempt to defend a young man without any experience in the criminal courts. McKellar’s senior partner insisted and McKellar was right inasmuch as his client was found to be guilty. Bringing his usual tenacity to the job, McKellar first pondered an appeal, but finally decided it would likely not be successful. McKellar then simply petitioned for a pardon from Governor Robert L. Taylor. The pardon was granted, which infuriated the trial judge, Julius J. Dubose. The judge had the now free killer jailed for carrying a pistol. The young man was tried and convicted and sent back to jail for eleven months and twenty-nine days. McKellar sent a copy of the court proceedings to Governor Taylor, who promptly pardoned the young man yet again. Judge Dubose became even angrier and had the young man indicted on still another charge. The judge gloated that Taylor could not pardon the boy any more often than he could convict him. Governor Taylor retorted the judge could not convict the young man any more often than he could pardon him. Judge Dubose finally laughed and McKellar’s client went free.

As governor, Bob Taylor asked the legislature to approve and build a facility for juvenile offenders. The legislature refused his request and as a result, Taylor pardoned almost every juvenile offender in the state. Bob Taylor was certainly a “pardoning governor”, but K. D. McKellar believed it was due to the governor’s tenderhearted nature.

If his opponents thought Bob Taylor was too lenient on criminals, the people of Tennessee didn’t much care. When Tennessee’s Democrats worried in 1896 the Republicans had a very real chance to win the governorship, they came running to Bob Taylor, begging him to run for a third term. Taylor was unenthused and pointed out his real desire was to serve in the United States Senate. Once again, Bob Taylor’s good nature got the better of him and he accepted the Democratic nomination and won the general election. Taylor refused to run for governor again in 1898 and returned to the lecture platform where he made a handsome living, commanding large fees for speaking. Unfortunately, McKellar’s assessment of Taylor’s financial acumen was all too accurate. Evidently the former governor could easily make money, but had a very hard time holding on to it.

Taylor’s senatorial ambitions continued to be thwarted by the legislature until 1906. Incumbent U. S. senator Edward W. Carmack was up for reelection that year and legislators had agreed to be bound by a special primary election. Taylor entered the senatorial primary and began stumping the state. Carmack, a red-headed and fiery former editor, was well able to take his own part in any quarrel and he was an excellent orator, but he proved to be no match for “Our Bob”, who still sang, played his fiddle and charmed his audiences. Taylor won the primary and the legislature duly elected him to the United States Senate.

Bob Taylor left for Washington, D. C. and his ability to spin entertaining yarns made him quite popular in the nation’s Capitol. One of “Our Bob’s” warmest admirers was a Republican, who also happened to be President of the United States: William Howard Taft. The two had first become acquainted while Taft was serving as Theodore Roosevelt’s Secretary of War. Senator Taylor accompanied Taft and several friends on the presidential yacht, the Mayflower, to Hampton Roads, Virginia. Taylor sat up well into the summer evenings enjoying the cool breezes blowing across the ship’s deck and entertained his fellow passengers with stories from his Tennessee experiences. Taft never forgot one such story, which involved a young man who enjoyed moonshine. The more moonshine the young man swilled, the more certain he became convinced he could lick anyone who challenged him. Soon, the boy was boasting he could beat all comers. Believing he had bested every man in Tennessee, the youngster finally encountered another lanky young man who proceeded to give him the thrashing of his life. The beaten and battered young man finally sighed and admitted he “had covered a little too much ground.”

Bob Taylor’s admirers in Washington ranged from the powerful to the powerless. Senator Taylor was especially popular with the Senate’s pages, many of whom he befriended.

Finally having achieved his long cherished ambition to win election to the United States Senate, Bob Taylor was appalled when he was once again called to run for governor by his fellow Democrats. Tennessee’s Democratic Party had been torn to pieces by incumbent governor Malcolm Patterson and his feud with former senator Edward Ward Carmack. The feud ended with Carmack shot and left dead in the gutter in Nashville. Patterson inflamed tensions by pardoning one of Carmack’s assailants, Colonel Duncan B. Cooper. Governor Patterson had been running for a third two-year term, but eventually discerned he could not be elected again. Dissident Democrats had announced their independence and joined Republicans in a “fusion” movement that threatened to win the governorship. Democrats quickly concluded they needed a candidate of surpassing popularity to forestall a GOP victory in the fall election. Only Bob Taylor fit that bill. With great reluctance, Taylor agreed to run and made a spirited campaign in the general election. Virtually everybody was astonished when Bob Taylor lost to Republican Ben W. Hooper. It was the only statewide election “Our Bob” had ever lost.

Taylor was devastated by his defeat, hardly believing his people could reject him at the polls. Kenneth McKellar believed the defeat led to Taylor’s early death, for the senator was heartbroken by his loss.

Fortunately, Taylor had not resigned his seat in the United States Senate to wage his gubernatorial campaign. Senator Taylor returned to Washington and resumed his senatorial duties. Taylor entered the hospital in the spring of 1912 for what was to have been a routine operation for gallstones. After the operation the senator became increasingly ill and never left Washington’s Providence Hospital alive. By the end of March, the Nashville Tennessean published an editorial noting Senator Taylor was critically ill. The editorial was more a prayer for the senator’s recovery and the Tennessean noted all political “swords are sheathed and every heart is bowed down” as Taylor hovered “on the brink of eternity.”

The following day the Tennessean’s banner headline announced the passing of Senator Robert Love Taylor.

For sometime, the senator had looked ill and worn. Taylor’s complexion was an unhealthy gray and his former energy and dissipated. Worst of all, his boundless sense of humor seemed to have disappeared. Still, Taylor was busy planning his reelection campaign that year. He had intended to go home to Tennessee, but only managed a brief visit to Nashville before returning to Washington. Taylor’s physician noted the senator was suffering from toxemia. Among the callers visiting Senator Taylor in the hospital were President and Mrs. Taft. The President was profoundly worried about his friend and made several visits, oftentimes bringing bouquets of American Beauty roses. Once Bob Taylor died, President and Mrs. Taft visited the Taylor apartment to personally express their sorrow to his widow. That day the President arrived with a bunch of lilies for Mrs. Taylor.

Bob Taylor spoke in the flowery and lyrical language that has passed away with the ages. When a fellow senator died, Taylor eulogized his dead friend, saying, “The flowers in the field rising from the countless graves; the unfolding leaves of the forest heralding the approach of summer; the orchards and the meadows bursting into bloom and the myriads of winged minstrels filling the world with melody; all are the Evangels of the Lord, demonstrating before our very eyes the universal victory of Life over Death.

“Mr. President, look how the rose hears the far away call of the sun and blushes in the presence of its god. Look how the violet comes forth from its tiny tomb and opens its glad, blue eyes to greet the spring. Are they not God’s own answer to the question, ‘If a man dies shall he live again’?”

For many, Bob Taylor never truly died. His funeral in Knoxville was the largest ever recorded, with 40,000 people gathered to pay their respects to “Our Bob.” The funeral procession accompanied Bob Taylor’s body to Old Gray Cemetery where he sleeps to this day.