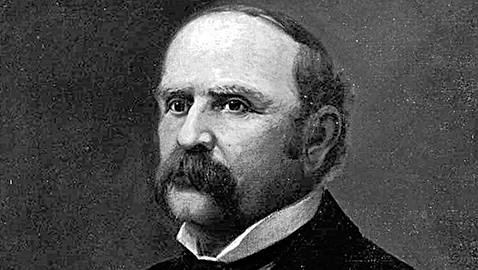

Benton McMillin was such a fixture in Tennessee politics he was regarded as the “Old Warhorse” of the Democratic Party in the state. After spending twenty years in Congress from Tennessee’s Fourth District, Benton McMillin twice served as governor of Tennessee. Yet the pinnacle of McMillin’s political ambition was to win election to the United States Senate. Like the proverbial old fire-horse, Benton McMillin seemed unable to ignore the call whenever the bell rang. McMillin made his last serious campaign at the ripe old age of seventy-seven and quite nearly won. Had it not been for his opponent’s majority in Edward H. Crump’s fiefdom of Memphis, Benton McMillin would have been the Democratic nominee to reclaim the governor’s mansion from Republican Alf Taylor in 1922.

Like many of his contemporaries, Benton McMillin sympathized with the Confederacy during the Civil War and while he wanted to join the Confederate Army, he was only sixteen years old when the war broke out and McMillin’s father flatly refused to give his permission. The teenager was captured by Union troops at one point during the Civil War and jailed as he adamantly refused to swear the federal Oath of Allegiance. McMillin’s rise in Tennessee politics began with a term in the state House of Representatives and eventual appointment by Governor James D. Porter to the bench, sitting as judge of the Fifth Judicial District. McMillin did not long remain cloaked in a judge’s robe; after only a year as judge Benton McMillin ran for Congress in 1878. The nominating convention was apparently contentious with 125 ballots required before a nominee was selected. Benton McMillin withdrew his name as a candidate several times, but finally emerged as the Democratic nominee on the 125th ballot. The thirty-two year old candidate had numerous friends inside the Fourth Congressional District and although he had been born in Kentucky, had practiced law with his uncle, Judge E.L. Gardenhire. McMillin had lived in Celina, the county seat of Clay County before moving to Carthage, Tennessee. Evidently campaigning at the time was hazardous, as the young candidate, while traveling from Hartsville to Dixon Springs, managed to turn over his buggy. McMillin “was bruised somewhat”, but apparently none the worse for wear. McMillin won the election and served ten terms in the U. S. House of Representatives.

For most of his time in Congress, Benton McMillin was a different kind of Democrat than what one would consider from a modern perspective. McMillin was wary of American global exploits, as he considered them to reek of imperialism. Congressman McMillin was also cautious about expenditures and was constant in his opposition to what he believed to be excess spending on the part of the government. Being a product of his time, Benton McMillin was also deeply opposed to the Lodge Bill, offered in 1890 by Massachusetts senator Henry Cabot Lodge. The Lodge Bill sought to afford protection to African-American voters in the South. As a senior Democrat in the House, McMillin served on the powerful Rules Committee and frequently challenged the autocratic Speaker of the House Thomas B. Reed of Maine. If Cordell Hull is today remembered by some as the father of the national income tax, Benton McMillin was its grandfather. It was Congressman McMillin who successfully offered an amendment to the Wilson – Gorman Tariff Act of 1894 that would have established the first income tax in the United States. Both McMillin and Hull represented Tennessee’s Fourth Congressional District and the farmers and residents of the small towns in the largely rural district would have been exempt from paying the income tax. The Wilson – Gorman Tariff Bill was challenged and heard by the U. S. Supreme Court. The high court struck down McMillin’s amendment as unconstitutional in 1895 in a decision rendered in Pollock v. Farmers’ Loan and Trust Company.

Benton McMillin’s first bid for the United States Senate came in 1897 after the death of Senator Isham G. Harris. McMillin was unsuccessful, but ran for and won the Democratic nomination for governor the following year. McMillin won the general election and was reelected to a second two-year term in 1900. Tennessee Republicans made an effort to defeat Governor McMillin in his reelection bid, but the Old Warhorse won handily. At the conclusion of his term as governor, Benton McMillin chose not to resume the practice of law, but instead went into the insurance business. Yet McMillin never gave up his interest in politics nor his desire to hold elective office. The lure of the United States Senate still intoxicated McMillin and he remained determined to return to Washington, D. C.

The first opportunity for Benton McMillin to return to Washington, D. C. was the unexpected death of Senator William B. Bate, who died days after having been sworn-in for a fourth term. Almost immediately McMillin and former governor Robert L. Taylor were candidates to succeed Bate. The Nashville Tennessean tried to assess the strength of the various candidates, which included incumbent governor James B. Frazier. According to the Tennessean, Dresden, Tennessee was a hotbed of support for McMillin, while Taylor and Governor Frazier seemed to be the favorites in Humboldt. Lexington, Tennessee seemed to favor Benton McMillin, although the Tennessean’s correspondent found that Governor Frazier “has some strong friends” in the area. Hardeman County appeared to be decidedly in favor of Robert L. Taylor. Friends of former governor McMillin gathered at the Duncan Hotel to ponder how best to promote their favorite’s candidacy for the Senate before the legislature. While both Benton McMillin and Robert L. Taylor retained strong followings all across the state, Governor James B. Frazier had an advantage in being a popular incumbent with his fingers on the levers of power. Frazier easily won election to the United States Senate.

Robert L. Taylor finally achieved his ambition of serving in the U. S. Senate when he won a primary election in 1906, defeating sitting Senator Edward Ward Carmack. Legislators promised to be bound by the decision of the voters. With the path to the Senate seemingly blocked for Benton McMillin, he had to consider other options. Perhaps hope flickered briefly when Taylor was convinced by party elders to run once again for governor in 1910. McMillin appeared to have finally reached his own goal of serving in the U. S. Senate that same year. Benton McMillin had won the primary election and campaigned throughout Tennessee in 1910 as the Democratic nominee for United States senator.

McMillin was touring his own Middle Tennessee at the beginning of July, speaking in his home city of Carthage, Shelbyville, Lewisburg, and Fayetteville. Still, some of McMillin’s friends were suspicious a trade of some sort had been made by Robert L. Taylor and disgraced Governor Malcolm Patterson. The Tennessean published a report from Bristol, Tennessee, stating McMillin partisans worried the Patterson “machine is making of McMillin a mere stalking horse with no intention of electing him to the Senate is the belief of many here.” In spite of McMillin having won the primary, the legislature still elected U. S. senators. Even though Malcolm Patterson had dropped his bid for a third term as governor, it was no secret he harbored senatorial ambitions of his own. The “fusion” movement of “Independent” Democrats, those Democrats who had bolted because of Governor Patterson, allied with Republicans, proved to be a very real threat in the general election. Although he campaigned heartily for the Democratic ticket, Benton McMillin watched helplessly as “Our Bob” lost to Republican Ben W. Hooper. As it turned out, Benton McMillin’s nomination for the U. S. Senate was up-ended by the same fusion movement in the legislature. While “regular” Democrats voted for McMillin for senator, independent Democrats divided their votes among other candidates, including the incumbent, James B. Frazier. After a deadlock, members of the legislature began withdrawing the names of several candidates and Luke Lea, publisher of the Tennessean was nominated. Lea was acceptable to the independent Democrats. Among those whose name had been withdrawn was Benton McMillin. Regular Democrats paid little attention to McMillin’s withdrawal and stubbornly continued to vote for the former governor. On the final ballot, the presiding officer announced Luke Lea had 68 votes, Benton McMillin had 48 votes, and the rest were scattered between three other candidates, including Lawrence D. Tyson of Knoxville. Luke Lea was elected to the United States Senate.

The Democratic Party in Tennessee remained badly split and it was not surprising they turned to Benton McMillin to oust Governor Hooper in 1912. McMillin suffered the same fate as Bob Taylor, losing to Hooper, who was supported by a coalition of Republicans and Independent Democrats, in the general election.

The good news from the 1912 election was Woodrow Wilson winning the White House. Democrats had been denied the presidency since the last administration of Grover Cleveland and with power came patronage. McMillin was appointed by President Wilson to serve as Minister to Peru. From 1913 until 1922, Benton McMillin was a diplomat, serving as Minister to Peru until 1919, when he became the American Minister to Guatemala. Despite the fact the Republicans had won the presidency in 1920, Warren Harding did not seem to be in a hurry to replace Benton McMillin. The former governor finally resigned his post in 1922 to hurry home to Tennessee to wage yet another campaign for governor.

The 1920 election had been a boon for Republicans in Tennessee. Not only had Warren G. Harding carried Tennessee, but the Volunteer State had elected a Republican as governor. Alf Taylor, brother of the late Robert L. Taylor, had defeated incumbent Albert H. Roberts. Republicans had won five of Tennessee’s nine congressional districts in the 1920 election, even managing to defeat Cordell Hull in McMillin’s old Fourth Congressional District.

In the 1922 Democratic primary, the seventy-seven year old Benton McMillin vigorously stumped the state and faced a credible challenger in forty-six year old Austin Peay. McMillin demonstrated his strength despite not having won an election since 1900. The former governor won Hamilton County, lost Knox County by less than 200 votes, and carried Davidson County. McMillin was also strong in many of Tennessee’s rural counties, especially inside the confines of his old congressional district. The difference was Shelby County, where Austin Peay won 9,079 votes to only 1,732 votes for McMillin. Peay also made a spectacular showing in his own Montgomery County, which he won 3,793 to a mere 130 votes for Benton McMillin. Ultimately, Benton McMillin won 59,992 votes to 63,940 votes for Austin Peay.

Benton McMillin continued to be active in Tennessee’s Democratic Party affairs, along with his wife, Lucille Foster McMillin. He made one last attempt to gain a seat in the U. S. Senate in 1930. McMillin’s filed as a candidate for the “short term” to fill the remainder of the term of the late Senator L. D. Tyson. It would be the last opportunity for the eighty-five year old former governor to serve in the Senate, albeit briefly. McMillin was to oppose the incumbent, William E. Brock of Chattanooga, who had been appointed to fill the vacancy left by Senator Tyson’s death. At the end of July 1931, Benton McMillin announced he would not run for the Senate. The former governor had finally given up his ambition to return to Washington, D.C. as Tennessee’s U.S. senator.

The eighty-seven year old Benton McMillin was seriously ailing in January of 1933. For fifty years, he had been one of the most prominent political figures in Tennessee. It is astonishing to think Benton McMillin was first elected to public office nine years after the end of the Civil War and he had managed the pre-convention presidential campaign of Franklin Roosevelt in 1932. Contracting pneumonia, former governor Benton McMillin told his doctor he felt “fine” immediately before lapsing into a coma and dying hours later. Tennessee’s old “Democratic warhorse” was gone.