By Ray Hill

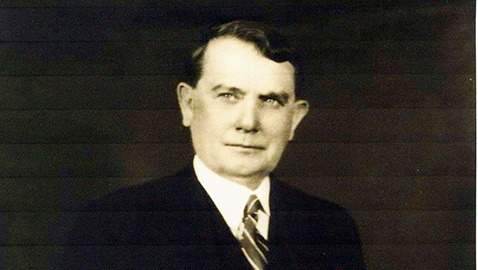

Despite intense pressure from constituents and his own political party, Senator John Knight Shields of Tennessee remained determined to vote his convictions as the United States Senate considered the Treaty of Versailles. John Knight Shields had been the only Democrat on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee to break ranks and support the treaty and American participation in the League of Nations with reservations. Henry Cabot Lodge, a Massachusetts Republican and Chairman of the Foreign Relations Committee had agreed to America joining the League, but only if the Senate adopted a series of reservations, or amendments, that he believed would protect the United States. President Woodrow Wilson, crippled by a stroke, lay in the White House as determined as ever to reject any and all reservations. Wilson demanded Democrats and the Senate approve the treaty as written.

Shields reiterated his position when speaking before the Senate in November of 1919. “I am pledged to support these reservations. I took that pledge when I appeared at the bar of the Senate and took the oath of office as a Senator to uphold the Constitution of the United States Senate,” Shields explained. Senator Shields said there had been a time when the people of the United States had been leery of making alliances with foreign nations and now the Senate was being asked to “go into an alliance with the whole world of the most complex and difficult character.”

Naturally, the independence of John Knight Shields did not stand him in good stead with the White House. Even before Shields persisted in supporting reservations to the Treaty of Versailles, President Woodrow Wilson had not liked the Tennessean. Only the pleading of Shields’ junior colleague, Senator Kenneth D. McKellar, persuaded the President from writing a public letter to the people of Tennessee denouncing Shields as no friend to the administration. Had Wilson written the letter, John Knight Shields would almost certainly have lost the Democratic primary to Governor Tom C. Rye in 1918. While Shields was opposed to the position taken by Wilson, Senator McKellar was backing the President wholeheartedly. The White House began to favor McKellar in matters of patronage over the senior senator. One such example was the matter of selecting the U. S. Marshal for the Middle Tennessee district. Vernon Sharp had been perceived as the leading contender once McKellar and Shields had protested the appointment of George Witt, which had been made by Attorney General Thomas Gregory just days before resigning his own office. The Witt appointment had been made without consulting either Tennessee senator and Vernon Sharp of Nashville was Senator Shields’ choice to fill the U. S. Marshal’s office. McKellar was backing Edward Albright of Gallatin, Tennessee. Prior to the debate over the treaty, most politically connected people in Tennessee believed Sharp was the heavy favorite for the appointment. The Nashville Tennessean reported there would likely be “reprisals” against the senior senator’s patronage recommendations and McKellar’s choice was expected to be nominated by the President. Likewise, McKellar’s pick for Tennessee’s commissioner for the enforcement of prohibition, Lewis Elkins, was expected to be selected. Nor was Shields expected to have much to say about the appointment of a postmaster for Nashville.

When John Knight Shields arrived in Knoxville from Washington, D. C. on November 21, 1919, he responded to a resolution approved by the Memphis Cotton Exchange and the Memphis Commercial Appeal. “I have no time now to prepare a statement concerning my support of reservations to the proposed League of Nations,” Shields said, “but I hope to do so as soon as I rest a little after the arduous sessions of the Senate. The resolution of the cotton brokers and the editorial to which you refer are no surprise to me. When I took my stand for American sovereignty and the rights of the American people against the proposed League of Nations without proper reservations to protect them, I expected such opposition.”

Shields pointed to special interests backing the treaty and the League of Nations, saying, “Great capitalists who desire to speculate in the deprecated bonds of the bankrupt nations of Europe and dealers in cotton and food products, who desire to exploit those countries for selfish purposes and wanted the United States as provided in the League of Nations to stabilize those governments and make their bonds and contracts valid, have spent over a million dollars under the auspices of the League to Enforce Peace in organizing branches of their league, paying public speakers and subsidizing newspapers to have the treaty ratified.” Senator Shields said he “expected opposition from these men” who cared less about the sovereignty of America than their own pocketbooks. Shields stressed his belief the proposed reservations were, with only one exception, “necessary to protect and maintain the sovereignty of our country and the rights of our people.”

“I cannot see how any American could object to a reservation to protect the interests of our own people,” Shields snapped.

To the charge he had had been less than candid with the people of Tennessee while he was seeking reelection in 1918, Senator Shields offered a reasonable explanation. “The fourteen points of President Wilson were not an issue in my campaign, and I never at any time pledged myself to support them,” Shields pointed out. “We were then in a war and if I had discussed the terms of peace I would have probably been denounced as a pacifist and a coward.” Shields said he refused to blindly follow any president, including Woodrow Wilson. The senator said the editor of the Commercial Appeal had “obeyed orders so long that it is possible he cannot now comprehend that a man and public officer can have convictions of his own…” Shields said not only would he not resign, but might well run again “if I live so long.”

Much of the press in Tennessee ignored the senator’s comments, or simply roasted him on the editorial pages yet again. The Bristol Herald-Courier in particular claimed Shields, while running for reelection “was a good and great friend of President Wilson” and flatly declared the senator had been “a firm believer in the Fourteen Points.” The Herald-Courier bitterly said Shields could have been reelected on no other platform other than one of support for Woodrow Wilson. The Herald-Courier sneered at the notion John Knight Shields had either a conscience or convictions of his own.

The attitude of Tennessee’s junior senator, Kenneth D. McKellar did nothing to alleviate the pressure upon John Knight Shields. McKellar had already been elected to Congress when Shields was first elected to the United States Senate in 1913. McKellar arrived in Congress in a 1911 special election, preceding the election of Woodrow Wilson as president in 1912. McKellar was an ardent supporter of Wilson and throughout his long congressional career and to the end of his life, believed Wilson was the greatest of the seven presidents he served with. Senator McKellar was also strongly in favor of the position taken by President Wilson for the Treaty of Versailles and the League of Nations. McKellar had toured the state of Tennessee speaking on behalf of the League. Senator McKellar missed few opportunities to drum up support for the League and in March of 1919, spoke before a Kiwanis Club in Nashville on behalf of the League of Nations. McKellar sent the president of the Kiwanis Club a copy of a telegram he had wired President Wilson, who was in Paris negotiating the Treaty of Versailles. McKellar told the President, “Ninety percent people of Tennessee, irrespective of party, favor League of Nations. Fisher concurs.” Fisher was Congressman Hubert Fisher, McKellar’s successor as the congressman from Shelby County and a former student of the President.

While speaking in Shelbyville, Tennessee for the League of Nations, the Nashville Tennessean, a newspaper not usually friendly to the senator (he had defeated Tennessean publisher Luke Lea), noted McKellar’s presentation was both clear and logical. The Tennessean was also careful to note McKellar’s speech was frequently interrupted by applause from the audience.

McKellar’s support for the League of Nations and backing of President Wilson gave the junior senator the upper hand in filling appointments and patronage in Tennessee, although there is no indication of personal hostilities between Tennessee’s two senators. McKellar made a speech on the floor of the Senate in September of 1919 strongly defending President Wilson and assailing the President’s critics. McKellar conceded there were foundations for some of the criticism hurled at Wilson, but in the senator’s opinion, most of it was “without rhyme or reason” as well as “without regard to facts.” Wilson’s Fourteen Points, the League of Nations, and the Treaty of Versailles caused McKellar to believe “everything the President did or said was exactly right.” Once the peace was won, McKellar told his colleagues the President’s “political enemies” descended upon Wilson and “politics superseded patriotism.” “They knew of course,” McKellar thundered, “that the chief honor of winning the war would naturally fall to President Wilson, and immediately upon the realization of that fact every one of those who during the war had claimed to be his friends but who were not, who claimed to be for his policies but who were not, began their tirade of abuse and vilification, and their machinations to prevent his getting credit for winning the war or securing peace.”

“Immediately,” McKellar said, “in their eyes, nothing that he had ever done or ever would do was or could be right.” “He was not only wrong when they said he was wrong, but he was wrong even when they, during the war, for their own political reasons, had said he was right,” Senator McKellar charged.

As the treaty languished in the Senate under the Republican majority and with President Wilson gravely ill in the White House, Senator McKellar presented his own compromise plan. McKellar attempted to peel off the votes of some Republican senators who were believed to be “mild reservationists” not entirely sympathetic to the position taken by Henry Cabot Lodge. Along with Senator John B. Kendrick of Wyoming, McKellar prepared a draft for presentation to the Senate. The heart of the McKellar – Kendrick proposal made clear the United State “assumes no obligation to protect foreign territory by use of her armed forces or an economic boycott without specific action and approval by Congress…”

McKellar had stopped in Memphis for two days following his journey to Alabama to attend the funeral of Senator John H. Bankhead of Alabama. Senator McKellar was then called back to Washington, D. C. by Senator Minority Leader Gilbert Hitchcock who said the Tennessean was urgently needed at the Capitol for ratification of the Treaty of Versailles. Before departing for Washington, McKellar told a reporter, “The situation looks more hopeful than ever for agreement on reservations and speedy ratification of the treaty. It now looks like we are going to do something right away.”

Senator McKellar’s optimism turned out to be unwarranted. When the Senate voted on March 15, 1920, all ten of the reservations promoted by Henry Cabot Lodge were approved by a two-to-one majority, which included fourteen Democrats. John Knight Shields was one of the fourteen Democrats voting with the Republicans for adoption, while K. D. McKellar voted against the measure. It was not long before Woodrow Wilson nemesis, Henry Cabot Lodge, moved to pass a resolution to return the treaty to the President stating it could not be ratified by the U. S. Senate. Both Senators McKellar and Shields voted against the proposal. Forty-nine senators voted for ratification of the treaty with the Lodge reservations, while thirty-five senators voted against it. It was the fourth time the treaty had failed to be ratified by the Senate.

The treaty was dead for the time being and the only hope for ratification was the opinion of the American people as expressed in the 1920 election.