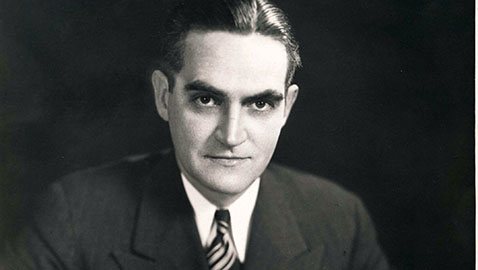

It was hardly surprising Joseph W. Byrns, Jr. had been elected to Congress from Tennessee’s “Hermitage District”, site of General Andrew Jackson’s plantation home. The district had been represented for twenty-eight years by Joseph W. Byrns, father of the current congressman in 1939. The elder Byrns had come up through the ranks in Congress, serving as Chairman of the House Appropriations Committee, Majority Leader and finally crowning his career as Speaker. Speaker Byrns had died suddenly in June of 1936 and friends quickly filed petitions qualifying the late Speaker’s only child as a candidate in the Democratic primary. Young Joe Byrns, Jr. announced he would not be a candidate and Richard M. Atkinson, a former District Attorney General for Davidson County, won the Democratic nomination for Congress by the slenderest of margins – – – 13 votes over his nearest competitor, Will T. Cheek.

Byrns was working as an attorney for the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation when he was recommended by Tennessee’s U. S. senators, Kenneth D. McKellar and George L. Berry, to serve as the Director for the HOLC for the Volunteer State. Oddly, the nomination seemed to stall, a mystery that was never explained. After a month of hanging fire, Byrns announced he would run for Congress to hold the seat his father had occupied for so many years.

Joe Byrns, Jr. said his platform was simple; he was supporting President Franklin Delano Roosevelt “100 per cent.” Byrns quickly received help throughout the Hermitage District from a network of supporters who had backed his father long before him. The thirty-four year-old candidate was critical of the incumbent who had strayed from the New Deal administration on more than one occasion. The Hermitage District was solidly Democratic, befitting a district that was home to the founder of the Democratic Party. The congressman would be selected inside the Democratic primary and Atkinson, whether true or not, was generally perceived to be the more conservative of the two, while Byrns was given much credit for all-out support of President Roosevelt. Atkinson, perhaps anticipating a challenge from Byrns, had sought to remove William M. Gupton as Postmaster of Nashville. Gupton had originally been appointed upon the recommendation of the senior Byrns and Atkinson would have been foolish not to suspect the postmaster would more than likely lend whatever aid he could to the son of his patron. Ordinarily, a sitting congressman of the president’s political party has the right to name the postmaster of his own home city. Unfortunately for Dick Atkinson, he ran afoul of the most powerful New Dealer and political power in Tennessee: Kenneth D. McKellar, the Volunteer State’s senior United States senator. McKellar also happened to be not only the ranking member of the Senate Appropriations Committee, but Chairman of the Senate Post Office & Post Roads Committee. Senator McKellar took the unusual step of writing Postmaster General James A. Farley, who was also coincidentally Chairman of the Democratic National Committee. When McKellar informed Postmaster General Farley the removal of William Gupton would be an “affront” to him, that was the end of the matter.

In a hard fought campaign where Atkinson remained on the defensive, Byrns won the Democratic nomination in 1938. Joe Byrns, Jr. received far more attention than was customary for a freshman congressman and when Clarence W. Turner died of a heart attack in 1939, the Nashville representative was given a seat on the important House Military Affairs Committee. Then came a misstep that would change the political fortunes of Joe Byrns, Jr. The most anticipated social event in Washington that season (and perhaps of any season) was the arrival of Great Britain’s King George VI and his Queen, Elizabeth. When the British Embassy announced only a few select members of the U. S. Senate and the leadership of the House would be invited to a reception hosted by the royals, Washington society lost its collective mind. The reception soon included a long receiving line allowing virtually every member of Congress to shake hands with the British monarchs.

Joe Byrns, Jr. went to shake hands with the King and Queen and when contacted by the Nashville Tennessean’s Washington bureau for a comment, the young congressman supposedly, replied, “What flat tires they turned out to be!”

The comment, whether actually said by Byrns to Lacey Reynolds or conjured by the newspaperman, brought shocked editorials from not only the Tennessean but also the Clarksville Leaf-Chronicle. Both Nashville and Clarksville were in the Hermitage District. The idea Joe Byrns, Jr. could say such a thing about guests was unthinkable in the South. Indeed, the editorial in the Leaf-Chronicle was entitled, “Poor Manners.” The comment made by Senator McKellar, referring to the royal couple as “lovely and fine” people was widely contrasted with the rather crass comment attributed to Congressman Byrns. The uproar was such Byrns sent a telegram to the Tennessean claiming he never made the comment attributed to him by Lacey Reynolds. It would certainly not be the last time Joe Byrns, Jr. made an unfortunate comment.

After a few weeks, the uproar about Byrns and his poor manners subsided and he returned to Nashville after Congress adjourned and tended to those things that a congressman normally does when back home. Byrns was the featured speaker at the weekly luncheon meeting of the Lions Club in the middle of September. Many Tennesseans, like most Americans, were growing more and more concerned as Germany invaded Poland, the beginning of World War II. Congressman Byrns told the members of the Lions Club, “I don’t think that the United States should be an international St. George riding over the world to kill dragons.” Byrns cautioned the Lions Club audience “even if we do think that Poland is right and Germany wrong, it is not any of our business to try to tell them what kind of government they must have over there.”

“And I don’t think it is the business of any nation what kind of government we have over here,” Byrns added. The young congressman also made the insightful comment that the First World War “the United States entered it with the hope of making the world safe for democracy, only to see less democracy after that war than there had ever been.”

Congressman Byrns concluded his informal talk by saying, “Think carefully and cautiously before you decide to hurl this country again into the maelstrom of militant insanity.”

A few days later, Congressman Joe Byrns, Jr. was repeating much of his message to the members of the American Legion Luncheon Club, which met at Nashville’s B & W Cafeteria. Byrns warned that if America felt the need to reach across the oceans, she might very well get her knuckles rapped. Byrns made a logical argument for neutrality, which was certainly the prevailing view across the country at the time. Few Americans wished to send more boys to fight in yet another European war. The congressman’s wife was the speaker at the Four Corners Garden Club, although her topic on the “Ancient Use of Herbs” was far different from her husband’s lectures on neutrality.

Byrns got some publicity in his district when he announced he was drafting legislation to increase the number of appointments to the military academies at Annapolis and West Point for each congressional district in the country. Byrns noted if there were an increase in the number of enlisted men, there would obviously be a need for more officers to command them. The young congressman got some even better publicity when his office announced the approval of a $51,893 Works Progress Administration project “for converting the old McConnell airfield into a modern city park with a nine-hole golf course…” The news came from a telegram sent by Congressman Byrns’ office to Nashville Mayor Thomas L. Cummings.

Byrns hurried back to Washington, D. C. for the special session of Congress called by President Roosevelt to consider revisions of neutrality legislation adopted in earlier sessions. The President was given strong support by the Tennessee Congressional delegation, not to mention Secretary of State Cordell Hull. Senator McKellar was especially vocal in backing Roosevelt. Every member of the Tennessee Congressional delegation in the House, with the exception of Republican Carroll Reece, voted to back the neutrality legislation supported by the Roosevelt administration. Even J. Will Taylor, the Republican congressman from Tennessee’s Second Congressional district, backed the administration. Byrns, Walter Chandler of Memphis, Herron Pearson, Wirt Courtney, Albert Gore, and newly elected Estes Kefauver of Chattanooga all voted for the neutrality bill.

While in Washington, D. C. Congressman Joe Byrns, Jr. gave a lecture on “The Confederate Navy” at the annual event sponsored by the District of Columbia Division of the United Daughters of the Confederacy. One of the listeners gathered to hear the young congressman was Peter Pierre Smith of Maryland, a ninety-six year-old Confederate veteran of the Civil War.

Byrns surprised some by refusing to vote for the adjournment of the special session of Congress. Byrns insisted Congress had some unfinished business, such as amending legislation affecting Tennessee tobacco growers, a not unpopular stance inside Tennessee’s Hermitage District. Congressman Byrns also said in a statement released to Tennessee newspapers it was his firm conviction Congress should be in continuous session so as “to advise with President Roosevelt” in perilous time which he believed were “fraught with possibilities of danger and disaster.” Perhaps thinking of the coming election in 1940, Byrns said his desire for Congress to remain in session was keeping his campaign pledge of 1938 to “stay on the job.”

Of course Congress did adjourn and Byrns hurried home to Nashville in November of 1939 where he made the presentation address on Armistice Day for a bust of Admiral Gleaves to be given to the City of Nashville, which was to be accepted by Mayor Cummings.

1939 was a difficult year for the Tennessee Congressional delegation as Death stalked its members. Three congressmen out of the nine member House delegation died during the year; Clarence W. Turner suffered a heart attack, while Sam D. McReynolds succumbed to heart disease and J. Will “Hillbilly Bill” Taylor died of a heart attack that November. Joe Byrns, Jr. gave a short, but moving tribute to the late Hillbilly Bill. “I am deeply grieved at the death of Hon. J. Will Taylor,” Byrns said in a statement provided to Tennessee newspapers. “He was my friend for many years and although he and I were members of opposite political parties, this did not interfere with our friendship. He was a real man, a hard fighter, but one who never struck below the belt. For such a man, all Tennessee should be in mourning.”

Byrns had more good news from the WPA and sent a telegram to announce Montgomery County’s application for funds totaling $83,098 had been approved. The money was to be used to “improve and construct” roads in Montgomery County under the “Farm-to-Market” program. Congressman Byrns notified G. G. McClure, who was the Road Superintendent for Montgomery County. Practically speaking, the road work would employ 140 men, which following the depths of the Great Depression was mighty welcome to most families.

As Christmas approached during the 1939 holiday season, Congressman Joe Byrns, Jr. was still performing the numerous personal and political chores expected of a member of the House of Representatives. Byrns was the guest speaker at the Band Cafeteria in Nashville where he regaled the members of the Women’s Political Union with his observations about the recent special session of Congress and the dangers of foreign wars.

Joseph W. Byrns, Jr. had just completed his first year as a member of the U. S. House of Representatives and aside from his unfortunate observation about the King and Queen of Great Britain, whether true or not, the young congressman appeared to be in good shape for the 1940 election.