Republicans had not really been a factor in statewide elections in Tennessee for the better part of almost half a century. There were those occasions when a Republican managed to win the governorship, usually due to some unusual circumstance that gave the GOP an opening. That had been the case in 1910 and 1912 when Ben W. Hooper had been elected governor and reelected two years later. The Democrats had ripped themselves asunder following a brutal primary contest between former United States senator Edward Ward Carmack and incumbent Malcolm Rice Patterson for the governorship in 1908. Carmack lost narrowly and resumed his occupation as a newspaper editor. The former senator had a knack for dipping his pen into vitriol and writing editorials that badly scalded his opponents. One of those opponents objected and Edward Ward Carmack met Colonel Duncan Cooper and the Colonel’s son Robin on a Nashville street. Shots were exchanged and Carmack lay dead. A court let Robin go free on a technicality while Patterson pardoned the Colonel and the outcry forced the governor to relinquish the Democratic nomination. One of the most popular Democrats in the state, Senator Robert Love Taylor, was induced to accept the gubernatorial nomination much against his own inclination and better judgment. The Democratic Party was too divided and Hooper won the election. Hooper was reelected in 1912 and both of Tennessee’s United States senators (elected by the General Assembly) were Independent Democrats, elected by a combination of Independent Democrats and Republicans against regular Democratic candidates. When Tom Rye was nominated for governor in 1914 and Democrats united around his candidacy, he was able to beat Hooper who was running for a third two-year term.

Tennessee Republicans had their best year for fifty years in 1920 when they elected Alf Taylor governor, Julian Campbell to the Tennessee Railroad & Public Utilities Commission (a statewide office) and five out of ten congressmen. Yet Republicans had never elected a United States senator. From 1900 until 1964, there were only two campaigns where Republicans waged a serious bid to win a seat in the United States Senate in the Volunteer State. Former Governor Ben W. Hooper was the GOP nominee for the U. S. Senate in 1916, the first election where Tennesseans went to the polls to select their own senator. Hooper was a credible candidate and won roughly 45% of the vote against Congressman Kenneth McKellar. Had either Malcolm Patterson or incumbent Senator Luke Lea been the Democratic nominee, Hooper might very well have had a chance of being elected as both were highly polarizing figures and there were thousands of Democrats who could not bring themselves to vote for either.

The quality of some of the senatorial nominees offered up by Tennessee Republicans was oftentimes high, while at other times, little more than a sacrificial offering. James A. Fowler, a distinguished attorney who had served under several U.S. presidents as a special assistant Attorney General and mayor of Knoxville, was the GOP senatorial nominee in 1928 to face McKellar. Herbert Hoover carried Tennessee that year, largely because the Democrats had nominated a Catholic and wringing “wet” for president. Fowler’s son Harley, also an able lawyer, was the Republican nominee for the United States Senate in a 1938 special election. Howard Baker, Sr., father of the future U.S. senator, was the GOP standard-bearer against Senator McKellar in 1940. Still, few Republicans were under the illusion their senatorial nominee would win the general election.

The first real effort by a Republican to win a seat in the United States Senate since the campaign of 1916 was in 1948. To understand that particular race, one must comprehend the circumstances surrounding the election. Nationally, morale amongst Democrats was at its nadir with presidential nominee Harry Truman. Say what they may, few Democrats believed Harry Truman could win the general election. The Democratic Party nationally was splintered into three factions; the regular Democrats who supported Truman, as well as the far-left group which coalesced around the new “Progressive Party” led by former vice president Henry A. Wallace. Lastly, there was the more conservative State’s Rights Party, which was comprised almost entirely of Southerners disgruntled with the national party or outraged by Truman’s civil rights platform. The “Dixiecrats” fielded their own ticket headed by South Carolina governor Strom Thurmond.

With the Democrats so deeply divided and the Republicans seemingly united behind their own nominee, New York governor Thomas E. Dewey, it was little wonder almost no one gave Harry Truman a chance of winning the fall election. Dewey’s running mate was Earl Warren, the governor of California (and later Chief Justice of the U. S. Supreme Court); virtually every election analyst forecasted the GOP ticket would sweep both California and New York, giving Republicans a big head start in the Electoral College.

If the situation nationally was bad for Democrats, that in Tennessee was, if anything, worse. Since the 1932 election, the combination of Senator Kenneth McKellar and Edward Hull Crump, leader of the Shelby County political organization, had dominated Tennessee’s Democratic Party and the state’s politics. McKellar and Crump had not always agreed on nominees, most notably in 1936 when the Memphis Boss favored former congressman Gordon Browning for the gubernatorial nomination in 1936. It had proved to be a terrible mistake with Crump and Browning having a falling out following the sudden death of Tennessee’s junior United States senator, Nathan L. Bachman, who had just been re-elected to a new six-year term. Browning moved decisively, albeit unwisely, to exterminate the Shelby County political machine. Although most historians have accepted the notion E. H. Crump was a statewide power and political dictator for Tennessee, the truth is his political potency was largely confined to his own domain of Shelby County where he reigned supreme. Crump was dependent upon McKellar’s vast network of personal friends, patronage army, and network of supporters to form a statewide organization. With Governor Browning seeking to reform elections in Tennessee by trying to pass a county unit plan in the legislature, Crump called on Senator McKellar for help. The county unit plan would make the popular vote meaningless, as each county would be assigned a certain number of votes according to size and population, much like the Electoral College. The final battle was waged in the 1938 Democratic primary, which would determine just precisely which faction would emerge dominant in Tennessee. The McKellar-Crump alliance backed Tom Stewart for the United States senatorial nomination and an unknown state senator from Shelbyville named Prentice Cooper for the gubernatorial nomination. If one of the two men had more to do with selecting the nominees, it was McKellar, while the Memphis Boss contented himself with destroying Gordon Browning. Tom Stewart beat Senator George L. Berry, a labor leader appointed to the Senate by Governor Browning following the death of Senator Bachman. Browning was soundly beaten by Prentice Cooper and for the next decade, every successful Democratic nominee for statewide office had the support of McKellar and Crump.

The change was wrought in 1948 by two things: the sales tax and Ed Crump’s greatest political mistake. Governor Jim Nance McCord had been politically prominent in his own Marshall County for decades and was the publisher and editor of a country newspaper and successful auctioneer. McCord served a single term in Congress before becoming the nominee for governor in 1944. Reelected in 1946 on a ticket with Senator McKellar, McCord believed education in Tennessee needed greater funding. Crump had been especially hostile to the idea of imposing a sales tax on Tennesseans and had fallen out with other governors who seemed interested in the idea, most notably, Hill McAlister. Somehow, Jim McCord convinced a very reluctant Crump to go along with the creation of the sales tax in Tennessee, with the greatest part of the new tax going for education, both higher and secondary. For the first time, Tennessee schoolchildren would have free textbooks. As it turned out, Tennesseans weren’t especially grateful for or supportive of the sales tax.

Crump told Tom Stewart in December of 1947 that he would not support the senator for reelection the next year. The Memphis Boss quite likely thought Stewart would meekly go back home to Winchester without complaint nor uttering a peep. The junior senator instead issued a fiery statement saying he would be a candidate for reelection and denounced Crump. Some of those around Crump apparently convinced the Memphis Boss to give his endorsement to an obscure judge of the Circuit Court from Cookeville, John A. Mitchell, who was a veteran of the First World War. Senator McKellar, who had always been quite friendly with Stewart, was highly skeptical that Mitchell could win a statewide race and reluctantly went along. Senator McKellar clearly disliked abandoning Stewart and felt bad about it. Crump’s decision to dump Stewart opened the door for a little-known, yet highly ambitious congressman from Tennessee’s Third District, Estes Kefauver, who had flirted with the idea of challenging McKellar in 1946. Kefauver later thought better of it and came to the conclusion there was an opening with Crump having blown apart the alliance. Although McKellar issued an endorsement of Judge Mitchell, most of his own political organization simply ignored it and backed Senator Stewart.

Before the 1948 primary campaign was over, Ed Crump realized he had made a critical mistake and seemed prepared to drop Judge Mitchell and throw his support behind Senator Stewart. The Kefauver campaign caught wind of it and publicly accused the Memphis Boss of contemplating exactly that. It stung Crump’s pride and he promptly denied any such intentions. That gave Kefauver the opportunity to win the Democratic primary with a narrow plurality. There is every reason to believe had Crump merely stayed with Tom Stewart the senator would have won the Democratic nomination. The governor’s race went no better for the McKellar – Crump alliance as Jim McCord was buried in an avalanche of votes from Tennesseans who disliked the sales tax, irrespective of what it went for and how it was spent. Worst of all, McCord lost to Crump’s old nemesis, former governor Gordon Browning.

The 1948 Democratic primary was not Ed Crump’s last political miscalculation. The Memphis Boss refused to back Harry Truman in the general election and declared his support for Strom Thurmond and the Dixiecrat ticket. Senator McKellar issued his own statement saying he was a Democrat and backed President Truman. Crump’s announcement caused whatever national influence the Memphis Boss had in national affairs to evaporate.

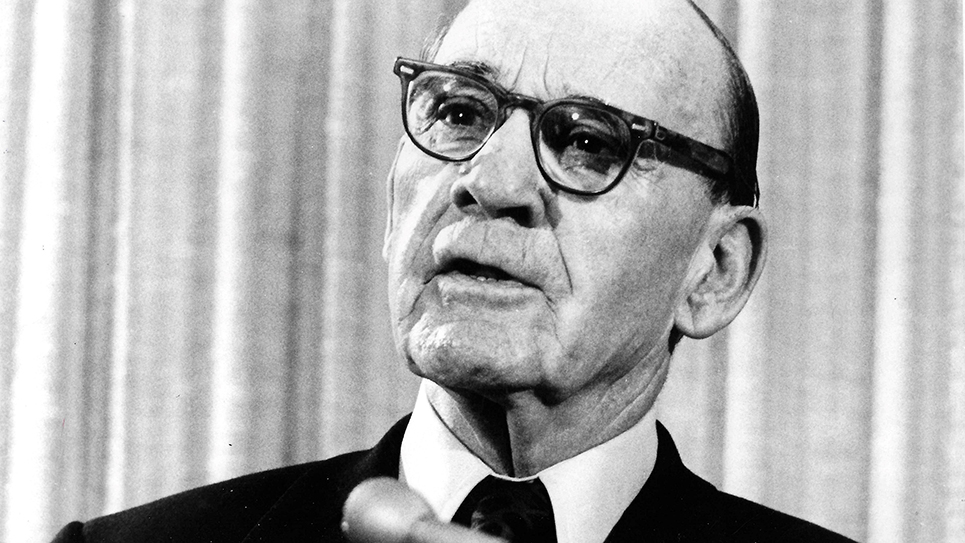

Crump’s refusal to support Harry Truman raised the hopes of Republicans in Tennessee. Confident in Tom Dewey’s election, the bitter primary campaigns and the split inside Tennessee’s Democratic Party gave some Volunteer State Republicans to believe a GOP candidate might very well win statewide. The Tennessee GOP nominated its candidates in a primary and produced a ticket calculated to appeal to a cross-section of voters. Carroll Reece, longtime congressman from upper East Tennessee, had just been eased out of the chairmanship of the Republican National Committee by Governor Dewey. Reece thought there was an opportunity to cap his career by serving a term in the United States Senate. Carroll Reece emerged as the GOP nominee for the Senate in 1948.

Roy Acuff, the legendary country music entertainer, was the duly nominated Republican candidate for governor. Acuff’s popularity was such that he had been the star of several low-budget movies throughout the 1940s, which were especially popular in much of the Southland. Acuff had amply demonstrated he could draw a crowd just about anywhere he went with his Smoky Mountain Boys and Carroll Reece had served in Congress for twenty-six years and was widely recognized as the most prominent Republican below the Mason – Dixon line. Reece was well known and widely respected in Republican councils at a time when Republicans in the South were as rare as hen’s teeth.

The Republicans could smell a whiff of victory in the air.