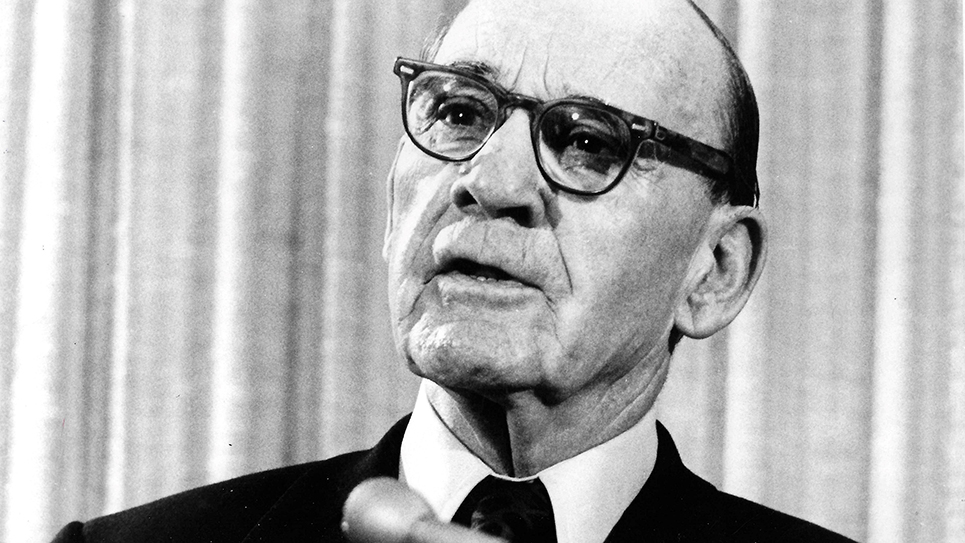

Congressman Clifford Davis was the last vestige of the old Crump machine still holding federal office in 1963. Davis had been in Congress since 1940 when he had won a special election to succeed Walter Chandler who had become mayor of Memphis. Davis was sixty-six years old and was slowing down and the one thing that no man can halt is time moving on. Times were changing and with them, there was a political realignment beginning in Shelby County.

The master of the Memphis machine, Edward Hull Crump, had died on October 16, 1954. Crump had apparently thought seriously about replacing Cliff Davis in Congress but had changed his mind after the congressman had been one of several House members seriously wounded on the House floor when a group of Puerto Rican nationalists had opened fire from the galleries. The resulting wave of sympathy had inoculated Cliff Davis from a political challenge.

Members of Congress usually have deep roots in the district they represent; certainly that is usually true in the county they call home. Although less true today than it was fifty years ago, Clifford Davis was solidly entrenched inside Tennessee’s Ninth Congressional District. One example will suffice to demonstrate Davis’ length and breadth of service to the people he represented. In 1964, highly respected Memphis attorney Edward W. Kuhn was elected president of the American Bar Association for the term beginning in 1965. Like so many Americans of his era, Ed Kuhn had worked hard to receive his education, earning a law degree from the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor in the depths of the Great Depression in 1933. To support himself, Kuhn had worked at a local funeral home during nights and had waited tables at the university hospital for his meals. For two summers, Ed Kuhn had been employed as a fireman by Clifford Davis, who had been the Fire & Police Commissioner for Memphis.

The voting habits of Tennesseans were ever so slowly changing; still, while the change was slow, it was inexorable. Tennessee had voted for Dwight D. Eisenhower for the presidency twice, in 1952 and 1956, albeit only narrowly. Eisenhower won 65,170 votes in Shelby County in 1952 when the Crump machine was still able to hold the line for Democratic presidential nominee Adlai Stevenson who won 71,779 ballots. By 1956, Crump was dead and the old machine had begun to disintegrate. Dwight Eisenhower narrowly managed to carry Shelby County in the general election. So, too, did Richard Nixon squeak to victory inside Shelby County in 1960. As more people settled into the Shelby County suburbs, so did the rising tide of Republicanism.

Clifford Davis had easily dispatched two serious opponents inside the Democratic primary in 1962, although there were clear warning signs in the vote totals. The two challengers won slightly more votes than the incumbent congressman. The general election shocked quite nearly everyone. Republican Bob James came within a whisker of upsetting the veteran congressman in the 1962 general election, losing by just over 1,200 votes.

Any sign of weakness on the part of an incumbent officeholder never fails to attract the interest of those coveting his/her office. George Grider, a member of the Shelby County Quarterly Court (the forerunner of the County Commission), was already preparing to run against Congressman Davis in the Democratic primary. Democrats were anticipating the candidacy of Arizona Senator Barry Goldwater and believed he would be a formidable figure in the Volunteer State. Early polling gave the Arizona solon a wide lead over LBJ in Tennessee. Of course, that was before Senator Goldwater proposed selling off the Tennessee Valley Authority.

Bob James was considered a sure bet to run for Congress from Shelby County once again, especially having only narrowly lost to Congressman Clifford Davis in 1962. James stated his belief that any candidate who tried to tie himself to Lyndon Johnson’s coattails in Tennessee would have a hard time getting elected. “The majority of the people in Shelby County are conservative,” James insisted to a writer for the Memphis Press-Scimitar. “Elections of the past 16 years bear this out. President Johnson, by his recent statements and actions, is pushing the Kennedy program.”

“Therefore, Shelby County will realize soon enough that a congressional candidate who ties himself to Johnson intends to help further socialize this country,” James said.

Bob James was born in Iowa in 1908 and was very much in the Republican tradition of supporting small business and vociferously anti-communist. A delegation of citizens from Memphis headed by attorney Lewis Donelson had come to his office in 1962 to urge him to run for Congress. James would go on to be elected to serve on the Memphis City Council for more than two decades and continued to serve his community for decades more. In fact, Bob James was ninety-three when his home was invaded by a burglar who held a knife to the former councilman’s throat and pinned him to the floor. The spry Bob James recovered and no less than former Governor Winfield Dunn (himself a long-time resident of Memphis) credited the former councilman with being the founder of the modern Republican Party in Shelby County. At age ninety-five, Bob James continued to watch as the award named for him was given to a deserving Republican for service to the community. James died in 2004.

By late December of 1963, an “informal” committee was put together whose purpose was to elect George Grider to Congress. Having retired from the Navy in 1957, Grider embarked upon a second career as an attorney, working with the prestigious firm of Burch, Porter & Johnson. Even with the formation of the committee, the fifty-one-year-old Grider told a reporter for the Memphis Commercial Appeal, “I have not really made up my mind whether to run.” “If I do run, I’m not going to get it by just fighting Cliff Davis,” Grider added. “I don’t want to be chosen as the lesser of several evils.”

By the end of 1963, it became increasingly clear Congressman Cliff Davis was not inclined to step aside for anyone. The Commercial Appeal reported that “informed observers” believed it was “practically certain” Davis would seek a fourteenth term in 1964.

State Senator Frank White, a thirty-nine-year-old who had served two terms in the legislature, announced his own candidacy for the Democratic nomination for the U. S. House of Representatives in January of 1964. First elected to the Tennessee House of Representatives in 1960 and the state Senate in 1962, Frank White was a young man in a hurry.

Congressman Davis hurried home in January, not to campaign, but because his elderly mother was in failing health. Shuttling from his apartment on Windover Road to the hospital, Davis found time to visit his office in the new federal building (which would later be named for him) for the first time. Asked by a reporter if he was running for reelection, Davis gave a rather terse reply, saying, “I know what’s in my mind, and I will make a statement later.”

The congressman pointed out he had served longer than any of his predecessors in the House of Representatives, including Davy Crockett, who had represented all of West Tennessee. Davis stated he was certain he could beat Bob James should he face the Republican in the general election once again. Congressman Davis said he also believed Tennessee would return to the Democratic Party in the 1964 general election.

The pipe-smoking Squire George Grider made official what pretty much everyone in Shelby County already knew: he was running for Congress. In his announcement, Grider said Tennessee’s Ninth District needed “sober, alert leadership from its representative.” Grider’s comment was an allusion to Congressman Davis’ supposed fondness for alcohol. “I am convinced that when a district’s representative in Congress is unable to provide aggressive leadership,” Grider said, “unable to be present for more than a fraction of the votes on issues that shape our destiny, we will do him and ourselves a distinct service to retire him. . .”

According to the Memphis Press-Scimitar, one-half hour after he had made the announcement he was running for Congress, George Grider telephoned State Senator Frank White to ask for a meeting. The next day the two men met and Grider frankly asked White to withdraw from the congressional race, a request the senator refused. Grider argued he believed he could best defeat Clifford Davis. Frank White disagreed, having described himself as a conservative while labeling Grider a liberal. White had made no secret of his firm belief he would appeal to more voters than would George Grider. Grider certainly did not let any grass grow under his feet. He greeted workers at the HumKo industrial plant as they came through the gates for the 7:00 a.m. shift the same week he made his announcement.

Congressman Cliff Davis had spent time away from Washington, remaining in Memphis where his mother Jessie Ott Davis lay dying. Mrs. Davis passed away on February 21, 1964, at the age of eighty-six. Cliff Davis sadly recalled his mother had been “my best booster all my life.” Floral tributes poured in from President and Mrs. Johnson, Governor and Mrs. Frank Clement, and several congressional colleagues of Davis.

It is interesting to note the 1960 census identified the population in Clifford Davis’ Ninth District as 627,019 residents. The two Congressional districts surrounding the Ninth were largely rural. Tennessee’s Seventh Congressional District was represented by Tom Murray of Jackson and had only 232,652 residents. Tennessee’s Eighth District was represented by Robert A. “Fats” Everett and had 223,387 residents. Clifford Davis represented more people than those of both the Seventh and Eighth Districts combined.

The second most populous Congressional district in the State of Tennessee was the Second, surrounding Knoxville with 497,121 people. Indeed, each of the three districts representing East Tennessee boasted over 400,000 residents. The Seventh and Eighth Districts were the least populous in all of Tennessee. Redistricting would substantially alter the political landscape in years to come.

Tennessee politics had already been roiled by the unexpected death of Senator Estes Kefauver in the summer of 1963. Kefauver’s death necessitated a special election for the remaining two years of the late senator’s unexpired term in 1964. It seemed every thirty years, both Tennessee seats in the United States Senate would be on the ballot; that was true in 1934, 1964 and 1994.

Two formidable Democrats entered the race to succeed Estes Kefauver; Congressman Ross Bass of Pulaski and Governor Frank Clement. Bass was considered the more liberal of the two candidates and the congressman came to Memphis where he was greeted by a number of supporters, which included George Grider.

Grider was one of the best-known members of the Shelby County Quarterly Court. The attorney had, according to the Nashville Tennessean, uncovered “dope peddling, brutality and homosexuality” which caused reforms to be enacted at the Shelby County Penal Farm. In 1964, Squire Grider was investigating alleged election irregularities, which had prompted additional investigations by the Shelby County District Attorney General’s office and “possibly the FBI.”

A demonstration of the powers of incumbency usually does no harm to a congressman. As George Grider was getting some attention from the news media locally, so, too, was Congressman Clifford Davis. Congressman Charles A. Buckley of New York, Chairman of the House Public Works Committee, had introduced a bill to name a proposed interstate highway bridge in Memphis for Cliff Davis. Buckley thought it a “fitting tribute to Clifford Davis for his 24 years of distinguished service in the House of Representatives, during which he has so ably represented the Tennessee Ninth Congressional District…” The bridge would cross the Mississippi River in North Memphis.

It was a not so subtle reminder to voters Cliff Davis had friends and influence inside the House of Representatives. The question to be answered in the coming election was how many friends did Cliff Davis have inside the district?