By Ray Hill

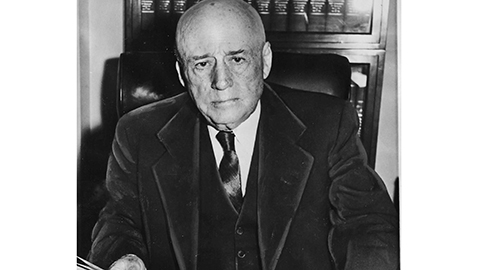

Few readers likely recall how very close the 1960 presidential election between John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon truly was. Kennedy won by a margin of 0.17 percent of the vote, some 112,827 votes. As Kennedy prepared to take over from President Dwight D. Eisenhower, the U. S. House of Representatives had been contending with increasing resistance to considering reform legislation inside the powerful House Rules Committee. The Speaker of the House was still Sam Rayburn, the longest serving Speaker in history. Rayburn frequently evaded classification by most historians, identified at times as a populist, liberal or even moderate Democrat. Rayburn was coming to the end of his forty-six years of continuous service in the House of Representatives. Born in Tennessee in 1882, Rayburn had first been elected to Congress in 1912 after serving as Speaker of the Texas House of Representatives. Rayburn became Speaker following the death of William B. Bankhead of Alabama in September of 1940 and remained in office until 1947 when Joe Martin, a Massachusetts Republican, became Speaker for two years. Rayburn was once again elected Speaker in 1949 and remained in office until 1953 when the Republicans once again controlled the House and Martin was reinstalled. The two men traded gavels for the final time in 1955 and Rayburn remained as Speaker of the House until his death in 1961.

Without a doubt, the somewhat obscure Rules Committee was the most powerful in the House with original as well as secondary jurisdiction over legislation proposed by members. In essence, the Rules Committee determined what legislation reached the floor of the House; it controlled the agenda of the House. The Rules Committee became the final resting ground for many a bill when the committee simply refused to give a particular bill a hearing. In fact, the House Rules Committee was indeed designed to keep frivolous legislation from reaching the floor. Were the Rules Committee not to do so, there would be so much legislation for congressmen to consider, it would choke the committee system to death and bring the flow of legislation and business to a halt.

Rayburn and Joe Martin, despite their political differences, were usually able to work out compromises on legislation in many instances. Martin’s own congressional district was thought to be trending Democratic, but his personal popularity and excellent constituent service had kept him in office. In 1959, following a rout of GOP candidates, Joe Martin was replaced as Minority Leader by his deputy, Charles Halleck of Indiana. Halleck was somewhat more combative and conservative than Martin had been and the Indianan immediately set out to establish an alliance with Howard W. Smith, Chairman of the House Rules Committee.

Howard W. Smith was a profoundly conservative Democrat, a breed that no longer exists inside the House of Representatives. Amongst Smith’s bag of tricks to disrupt the flow of legislation were simply refusing to call the committee together, the power to set the agenda of the House Rules Committee, and summon witnesses. In 1959, the membership of the House Rules Committee was set at twelve with eight Democrats and four Republicans. In spite of the number of the Democrats on the committee, the Republicans helped to actually control the Rules Committee as Howard Smith and William Colmer of Mississippi were conservatives and joined the GOP members in blocking many bills supported by the Democratic majority. The conservative coalition in the House proved to be so strong even Rayburn could not thwart it through his own personal influence. Speaker Rayburn suffered a number of setbacks as the Eisenhower administration drew to a close and the 1960 presidential campaign raged between Kennedy and Nixon. The conservatives did all they could to embarrass John F. Kennedy, which in turn, embarrassed Speaker Sam Rayburn. Of course while the presidential campaign was under way, so too were the congressional campaigns, a subject of much interest to Sam Rayburn. Congressmen Smith and Colmer helped the Republicans on the House Rules Committee to kill bills affecting the minimum wage, education, and public housing. Following Kennedy’s narrow election to the presidency, Sam Rayburn decided he had no other choice but to act to curb the power of Judge Smith and the House Rules Committee.

The Speaker flew to Palm Beach, Florida to visit with the President-Elect at the Kennedy compound to discuss the problem of the House Rules Committee. Kennedy, having served for six years as a congressman, realized Rayburn’s importance in the House and pledged his cooperation and support. Kennedy promised not to interfere in internal House matters.

Sam Rayburn gave consideration to several alternatives available to him, one of which was pressed by Rayburn’s protégé and the incoming vice president, Lyndon Johnson. The wily Johnson urged Rayburn to remove William Colmer from the Rules Committee, a move that would cripple the conservative coalition. LBJ believed it was a party matter and should be handled internally. Johnson thought removing Colmer from the Rules Committee and replacing the conservative Mississippian with a moderate or liberal Democrat would resolve the problem and gives Democrats a working majority on the committee. Certainly Speaker Rayburn had good cause to remove William Colmer as the Mississippi congressman had openly opposed the candidacy of the Catholic Kennedy during the recent presidential campaign. Party apostasy was anathema to most Democrats in the House. Rayburn was fearful that approach might very well backfire as Southern Democrats at the time composed the backbone of much of the Democratic majority in Congress. Alienating the Southerners might very well cause a realignment of the political parties. Lyndon Johnson later accomplished that in 1964.

Rayburn preferred compromise and conciliation as opposed to a brawl, but the Speaker was not at all afraid of a fight. Speaker Rayburn chose to try and enlarge the Rules Committee’s full membership to fifteen, which was permissible according to the rules of the House. That would allow Rayburn to appoint three more moderate or liberal Democrats to the committee and give Democrats an eight to seven advantage over the conservative coalition. That particular approach was not as offensive to Southern Democrats and there were a goodly number of moderates among the Southern contingent in Congress who would approve the strategy.

Rayburn sat in the Speaker’s chair on the dais of the House of Representatives and made no effort to challenge the rules as adopted by the full membership of the House. The shrewd Rayburn allowed the rumor to spread he was considering removing William Colmer from the Rules Committee and saw to it the gossip was spread to the newspaper reporters who gleefully printed it. The fanning of the flames of the Colmer removal by the news media helped to keep members of the conservative coalition off balance and confused. Rayburn carefully assessed support inside the House to enlarge the committee and sought strategic assistance from President Kennedy and the White House. True to his word, JFK and high ranking staff members placed personal calls to congressmen who were doubtful to lobby for support. A rickety alliance of a handful of special interest groups mounted a campaign to support the Speaker’s efforts including the AFL-CIO, the League of Women Voters, and the National Education Association. Yet the foundation supporting the move was Rayburn’s own influence inside the House. The Speaker was personally popular among his fellow Democrats and had performed innumerable favors for and extended limitless courtesies to his congressmen. Few members forgot the Speaker wielded great influence in determining a member’s committee assignments. There was no more effective lobbyist for expanding the membership of the House Rules Committee than Sam Rayburn himself.

Howard W. Smith had been a congressman for quite some time as well as the “Judge,” attempted to reach a compromise with the Speaker. Rayburn considered leaving the membership untouched if Judge Smith would give his word all legislation pushed by the Kennedy administration be given a fair hearing by the Rules Committee. Judge Smith and the Speaker could reach no agreement between them. On January 11, 1961 Speaker Sam Rayburn publicly announced he would try and expand the membership of the House Rules Committee. Some of the more liberal members of the Democratic caucus called for Congressman Bill Colmer to be removed from the Rules Committee and some even demanded Howard Smith be removed as well. The politically astute Sam Rayburn chose not to confront the Southerners so directly.

The Speaker seemed to have suffered a setback when the Republicans in the House of Representatives voted to oppose Rayburn. That gave Judge Smith the confidence to believe the coalition between conservative Democrats and House Republicans would deal Sam Rayburn one of his rare defeats on the floor. That same confidence, as well as a small measure of caution, caused Judge Smith to allow the matter out of the Rules Committee for a vote. The element of caution was the Speaker could still easily remove William Colmer as a member of the committee and nobody understood that any better than Howard Smith.

As the full vote approached Judge Smith remained confident while Sam Rayburn was fearful. Speaker Rayburn realized all too well just what defeat would mean to his personal and political prestige, as well as the potentially dire consequences to the success of the Kennedy administration. Defeat would mean Judge Howard Smith and the conservative coalition in the Rules Committee would be the single most powerful entity in the U. S. House of Representatives. No one in the House knew where the votes were better than Sam Rayburn and the Speaker sought out moderate Republicans for help and support. Some of Rayburn’s colleagues from his home state of Texas nervously reported an increase in their mail from constituents who were skeptical or outright opposed to enlarging the Rules Committee. Rayburn acknowledged he had received similar letters and dismissed them as having been written by people who had voted for Richard Nixon rather than John F. Kennedy and were nothing less than “poor losers” who wanted the Kennedy administration to fail. His fellow Texans split in their support of the Speaker, with fifteen backing Rayburn and seven opposed the enlargement of the Rules Committee.

A week before the vote, Judge Smith sensed support for Speaker Rayburn was growing and he was shaken. Smith proposed a compromise. The Judge proposed parsing out Kennedy administration legislation; Smith offered to report out five administration bills for consideration by the House. Speaker Rayburn consulted the White House and refused Smith’s proposed compromise. President Kennedy naturally gave his full backing to the Speaker and said the New Frontier would comprise perhaps ten or twelve major legislative proposals.

January 31, 1961 saw the House of Representatives consider Resolution 127, the plan to expand the membership of the Rules Committee from twelve members to fifteen. The most dramatic moment was when Sam Rayburn descended from the Speaker’s dais to speak to his fellow congressmen on the floor of the House. Rayburn in his typically matter-of-fact and blunt language explained why he wanted Resolution 127 passed. It boiled down to one thing: the Speaker did not believe one committee in the House should have the power and authority to halt all legislation. The vote was remarkably close and as the last five votes were cast, the congressmen and the folks in the House galleries were utterly silent. The final vote was 217 – 212 in favor of enlarging the House Rules Committee. The power of Judge Howard Smith inside the Rules Committee was broken. Still the conservative coalition defeated several Kennedy administration priorities but the Rules Committee only refused one White House bill, a school aid package.

It was the last great victory of Sam Rayburn’s long House career. Sam Rayburn died that same year of cancer and Howard W. Smith remained in Congress until he was defeated in the Democratic primary in his Virginia district in 1966 by a liberal Democrat, George Rawlings. Rawlings lost the general election to a conservative Republican William Lloyd Scott.