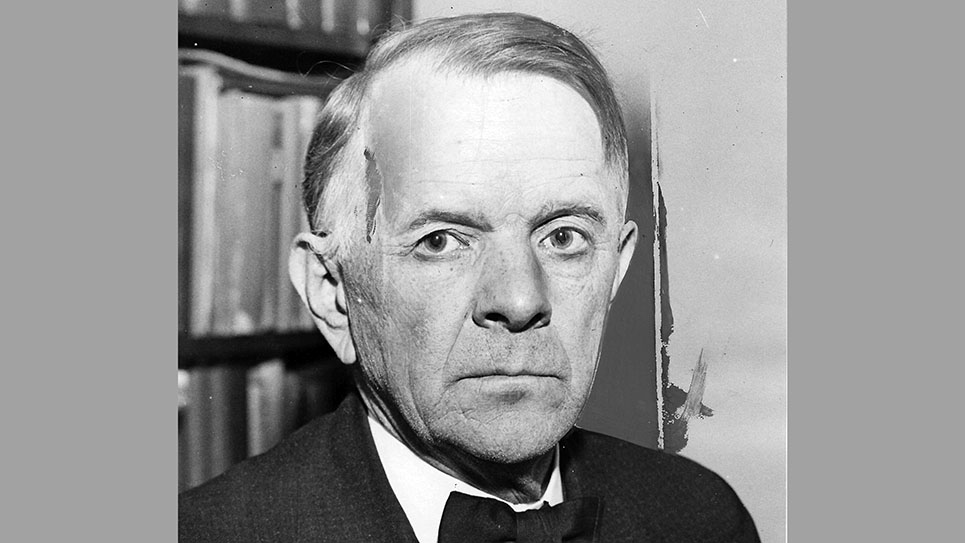

The Gentleman From Alabama: George Huddleston

By Ray Hill

Courtly, nicely dressed and usually wearing a black bowtie, George Huddleston, to all outward appearances, seemed to be a typical Southern congressman. A fiery speaker, Huddleston had been a successful attorney in Birmingham, although he preferred representing the employees rather than the employers. One of the best debaters in the House of Representatives during the decades he served in Congress, George Huddleston wielded a frequently tart tongue to powerful effect. Yet George Huddleston was not at all a typical Southern congressman of his time. The congressman was a critic of the Ku Klux Klan when that organization was highly powerful in Alabama. When first elected to Congress, George Huddleston was a strong advocate for the passage of progressive laws, as well as being one of the very few Southern congressman friendly to organized labor and supportive of the idea of racial equality.

Described by the premier news magazine of its day, TIME, as a “thin little wisp of a man who wears slippers in his office.” TIME noted Congressman Huddleston’s penchant for giving in to “vast and vociferous indignations.” The news magazine thought the personally wealthy Huddleston was “the South’s only radical.”

One of the more notable episodes of Congressman George Huddleston’s indignation was his breaking a ketchup bottle over the head of his primary opponent during a heated argument in a diner.

Another example of Huddleston’s vast indignation was his reaction to one of the most hard-fought issues during his time in Congress; the Wheeler-Rayburn Public Utility Bill, which would dissolve the great holding companies within seven years. The mighty private power interests fought back with an army of shrewd and very well-paid lobbyists, which descended upon the Capitol. Even the influence of the most popular Democrat in the country, President Franklin D. Roosevelt, seemed to fade in the onslaught by the horde of power lobbyists. The House whips found it was some thirty votes away from a majority, even with the pressure being exerted by the White House and the congressional leadership. The lobbyists had shrewdly encouraged the public to inundate Congress with letters and telegrams by scaring the hell out of them, warning folks their savings would disappear if the Wheeler-Rayburn Bill were passed by the House of Representatives.

The gentleman from Alabama, Congressman George Huddleston, spoke from the floor of the House, bellowing what was needed was “regulation” rather than “vengeance.” Huddleston scolded both sides involved in the bitter battle. “I deplore these outside influences,” Huddleston told his colleagues. “Before we had the first hearing on this bill the chairman of our committee (Sam Rayburn of Texas) radioed from one end of the country to the other telling people how bad the utilities were and how much this kind of legislation was needed,” Huddleston cried.

“He was not alone in riding this wave,” Huddleston said darkly. “The chief executive through his all-powerful influence had repeatedly done so. Let us have done with this talk of propaganda. Both sides are guilty. Both have interfered with a fair and just decision upon the part of Congress.”

Born in Lebanon in Wilson County, Tennessee, George Huddleston earned his law degree from Cumberland School of Law. Huddleston moved to Birmingham, Alabama, where he practiced law from 1891 until 1911 when he retired, purchasing 50,000 acres “in the piney hills of Shelby County.” First elected in 1914, George Huddleston was reelected every two years until 1936. Huddleston was a productive congressman, seeking to label products produced by either child or prison labor for consumers. When the administration of President Woodrow Wilson curtailed the right to free speech, Congressman Huddleston snapped, “In a time like this. . .it takes a lion-hearted courage for a man to stand up on his feet and dare to speak for peace.” Huddleston worked for the repeal of the 1918 Sedition Bill precisely because of its oppressive restrictions upon free speech.

George Huddleston had been opposed to the entry of the United States in the First World War as well as the Selective Service Act. Congressman Huddleston did vote for the declaration of war against the German Empire and her allies. Like many of his fellow progressives in Congress, Huddleston believed the burden of paying for the war should come out of the pocketbooks of big business, industrialists, and the publishers who stood to profit from the conflict.

George Huddleston first came to Congress by succeeding a towering figure in both national and Alabama politics. When Congressman Oscar W. Underwood moved from the House to the United States Senate, George Huddleston ran in the Democratic primary to succeed him. The young attorney ran on the slogan of “Honesty and Independence.” For 22 years, George Huddleston served in the House of Representatives, representing Birmingham. Upon his arrival in Washington, D.C., the new congressman was assigned to the House Foreign Affairs Committee.

When he was first elected, Huddleston was considered a bright-eyed liberal, but he also lived up to his slogan of being independent in his thinking. Many observers thought the Alabama congressman became increasingly conservative the longer he remained in the House. By the advent of Franklin Roosevelt and the New Deal, George Huddleston seemed to be drifting rightward. Time and again during the New Deal, Huddleston reiterated his “Independent” brand. Huddleston’s opposition to the Wheeler-Rayburn utility bill did not sit well with thousands of his constituents who considered the Tennessee Valley Authority to be one of the greatest things ever accomplished by the federal government on behalf of the people.

Congressman Huddleston rejected the notion he had become more conservative over time. “My principles remain now as always – – – I have not changed,” Huddleston insisted. “Some who once criticized me as radical now call me conservative. The same is in them and not me.”

Huddleston was acutely aware of the suffering inflicted upon his own people in particular and Americans in general. Testifying on behalf of a bill in a Senate committee, Congressman Huddleston bluntly told senators, “Any thought that there has been no starvation, that no man has starved and no man will starve is the rankest nonsense. Men are actually starving in their thousands today … ”

To those who doubted his liberalism, Huddleston pointed to three New Deal measures, which he had proposed before they were passed during the New Deal. Congressman Huddleston had sponsored legislation for home building, which became law under President Roosevelt’s Home Loan Act. Huddleston had also sponsored a bill to provide aid and relief to those citizens left destitute by the Great Depression before the New Deal. George Huddleston was also one of the first Members of Congress to advocate for public works legislation, which became a reality during the New Deal.

After being reelected to the House in 1916, the 47-year-old Congressman George Huddleston married Bertha Baxley the following year. The couple had five children. Throughout his career in Congress, most of the newspapers in Alabama railed against George Huddleston because of his economic views. Some newspaper editors flatly called Congressman Huddleston a “socialist.” The opposition to the congressman in his Birmingham led to a serious opponent inside the Democratic primary in 1918, but Huddleston won a relatively close race, winning with big majorities in the more rural areas, as well as carrying those precincts where miners made up most of the voting base. Congressman Huddleston argued for the rights of immigrants to live peacefully, without harassment and was supportive of the American Federation of Labor, which was anathema to many businessmen. The congressman’s largely pacificist point of view caused the Birmingham News to call his own patriotism and loyalty to country into question during the First World War. Congressman Huddleston had riled President Wilson enough so that the occupant of the White House sent a public letter condemning Huddleston’s voting record in the House of Representatives.

Yet there were limits to George Huddleston’s political independence. Although outspoken in his opposition to the Ku Klux Klan, the congressman voted against an anti-lynching bill in 1922. Huddleston realized to do otherwise would jeopardize his standing in his congressional district. Huddleston worked hard to pass legislation to help unemployed veterans get jobs and was one of the moving spirits in the passage of the 1933 Securities Act, which brought about federal regulation of the financial industry following the crash of the stock market and the onset of the Great Depression.

Congressman Huddleston was caustic in his criticisms of President Herbert Hoover for having failed to alleviate much of the suffering caused by the Depression. The Alabama congressman was chosen by his party to respond to President Hoover’s State of the Union address in 1931. Huddleston hammered the Chief Executive for Hoover’s failure to provide aid to Americans impoverished by the Depression. Huddleston personally sponsored a bill to allocate $100 million to ease the misery of people by giving them direct relief. Congressman Huddleston’s bill was the first of its kind in American history. The Alabama congressman’s bill was quickly rejected by Hoover.

Although later excoriated for his own failure to rubber stamp every measure sought by President Roosevelt, George Huddleston proved to be a leader in shepherding New Deal legislation through the House. Huddleston personally steered no less than fifteen major bills through the House of Representatives. George Huddleston seemed likely to remain in Congress as long as he wished. The Alabamian had been reelected to the House in 1934 by winning the only election that mattered, the Democratic primary, with better than 60% of the vote.

As it oftentimes the case, political independence frequently carries with it a hefty price tag. Congressman Huddleston’s opposition to the utilities bill helped to seriously erode his support back home. Huddleston faced 42-year-old Luther Patrick in the Democratic primary. Patrick was an attorney by profession, but he was also a sometime poet and radio personality and humorist. Patrick homed in on Huddleston’s having refused to support the president, as well as depicting the incumbent as having sided with the private power lobby instead of public power and the people. It was a politically potent argument in Tennessee, home of the TVA, and almost equally so in Alabama.

Facing five opponents in the first primary, Congressman George Huddleston won a plurality of the vote, but the incumbent was only ahead of Luther Patrick by fewer than 4,000 ballots. With no candidate having received a majority of the vote, the congressman and Patrick faced one another in the run-off election. The contest was hard fought and bitter, the highlight of the race was the two opponents meeting in a restaurant where the congressman broke a bottle of ketchup or “sauce” over Luther Patrick’s head. Patrick insinuated the members of Alabama’s congressional delegation wished to see George Huddleston defeated for reelection. Congressman Sam Hobbs promptly wrote Patrick a letter, a copy of which he released to the press, denying the delegation was opposed to Huddleston.

As the election results trickled in, Huddleston may well have wished he had hit Patrick harder. The challenger handily defeated the incumbent, winning quite nearly 60% of the vote.

George Huddleston never again sought public office. Having sold off 46,000 of his 50,000 acres, the former congressman had invested his profits in real estate, which provided him a nice income. Once defeated, Congressman George Huddleston went home to Alabama. As is almost always the case, the rejection by the voters of his district was painful and stung to the quick. Huddleston refused to issue any statements or give an interview to newsmen for a full decade before breaking his self-imposed silence.

George Huddleston lived long enough to see a vindication of sorts from his defeat for reelection. That came with the election of his son and namesake to Congress in 1954. What the elder Huddleston did not live to see was the astonishing defeat of his son in 1964 by, of all things, a Republican. As Barry Goldwater was carrying Alabama easily over Lyndon Johnson, John Buchanan beat Congressman George Huddleston Jr. by 21%.

The former congressman died after a long illness at his home at the age of ninety.

© 2024 Ray Hill