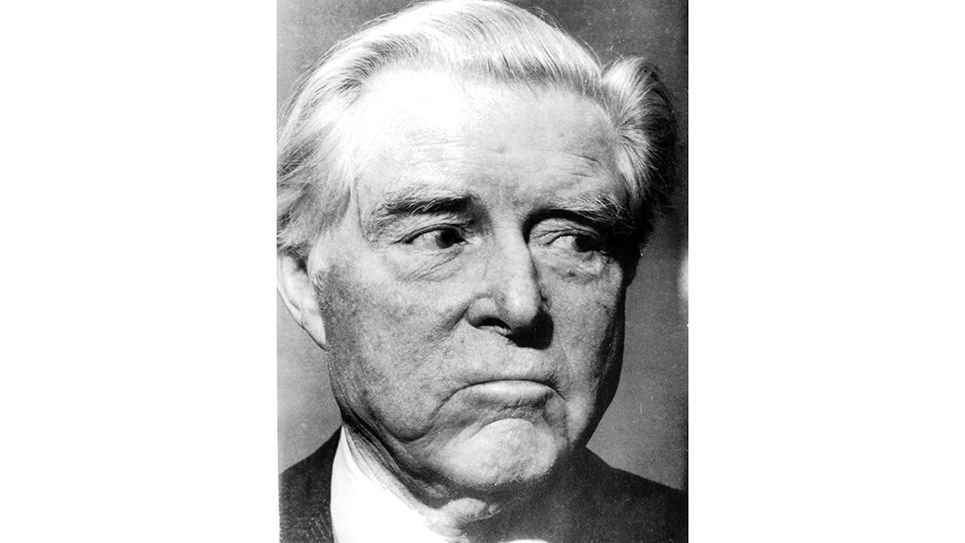

The Gentleman From Indiana: Ray J. Madden

Ray John Madden served in the U. S. House of Representatives from 1943 until 1977, a total of 34 years, representing the most solidly Democratic district in Indiana. A big, bluff man with a thick thatch of hair, Ray Madden was known for giving what one newsman recalled as “too candid answers” to questions asked, and his “salty” language. Serving with seven presidents and rising to chair the powerful House Rules Committee, Madden was heard advising members to “hold on to your underwear” in preparation for receiving certain information.

As he aged, Ray Madden especially liked to tell the story of Georgia Congressman Eugene E. Cox, who had patiently waited 30 years to become the chairman of the House Rules Committee. Finally, the path was clear and in the next Congress, Cox would become the chairman. The Georgian died before the next session of Congress opened.

It was Ray Madden who headed a special committee of the House, which interviewed numerous witnesses in not only the United States but also Great Britain, Germany and Italy following the Second World War, to investigate the Katyn massacre. Some 22,000 Polish military officers, intelligentsia, prisoners of war, police officers, and the chief Rabbi of the Polish Army were all executed. For years, there was doubt as to whether the murders had been committed by the Nazis or the Soviets. Ray Madden helped to find the truth, discovering the orders for the mass executions had been issued by Josef Stalin, the brutal Soviet dictator, through the Politburo.

The Soviet government continued to deny its role in the mass murders until it acknowledged its responsibility through the actions of the dreaded NKVD (the Soviet secret police).

Born in Minnesota, Madden was elected municipal judge in Omaha at age 24, meeting President Woodrow Wilson, who teased him about his youthful appearance. Entering the U.S. Navy during World War I, Madden returned to the United States and settled in Gary, Indiana, after earning a law degree. A committed Democrat, Madden attended every national convention of his party from 1940 through 1968.

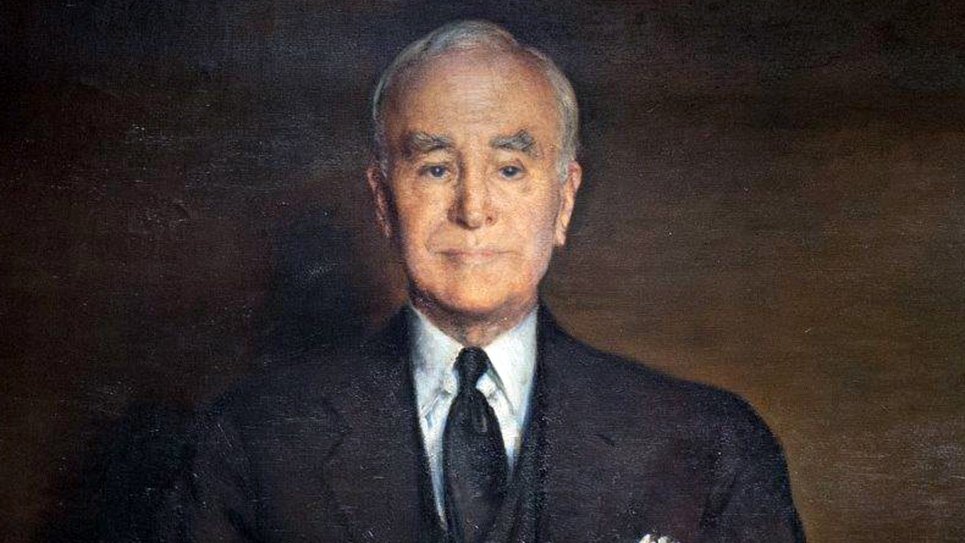

Ray Madden also worked his way up the political ladder in his adopted home of Gary, serving as city comptroller, and then winning election as the treasurer for Lake County. The first Democrat to represent the district surrounding Gary was William Schulte, who had first been elected in the 1932 tidal wave that carried Franklin D. Roosevelt to the White House. By 1942, Schulte had served a decade in Congress and Madden, then 50 years old, challenged the incumbent.

Schulte was a colorful figure, who variously worked as a theatre stage manager, member of a dance team, city alderman for Hammond, Indiana, and fireman (his brother was the fire chief). William Schulte was never a favorite of the local Lake County Democratic machine. To win the nomination for Congress, Schulte had to beat the favorite of the machine, which he did by just over 300 votes. Congressman Schulte was a favorite of organized labor and was a card-carrying member of the Theatrical Stage Employees Union.

Ray Madden had challenged Schulte because of the congressman’s political vulnerability due to his “consistent opposition to this country’s entry into” the Second World War. Members of Congress who had been against American intervention began losing their seats oftentimes following Pearl Harbor. Some in organized labor were angry with Schulte for voting against funding for the Dies Committee, which purported to ferret out un-American activities. Madden ran as a supporter of President Roosevelt, both domestically and in FDR’s foreign policy. Much of Schulte’s upset loss had to do with the congressman’s refusal to hire precinct workers for the election, as well as having ignored long-time party leaders.

Once in the House of Representatives, Ray Madden approached the formidable speaker of the House, Sam Rayburn of Texas, and requested to be a member of the House Post Office and Post Roads Committee. Usually considered a minor committee, Rayburn was only too happy to oblige. As a freshman legislator, Madden sponsored a bill to raise the pay of postal employees, which passed both the House and the Senate. The freshman congressman had endeared himself to the postal unions and its members. “I wondered why you wanted to get on that damned committee,” Rayburn told Madden.

After brief service on the Naval Affairs Committee in the House, which was ruled with an autocratic gavel by Georgia’s Carl Vinson, the inquisitive congressman from Indiana was moved to the House Education & Labor Committee. The reason was that Vinson didn’t much care for fellow Democrats who questioned either his authority or judgment. While serving on the Education & Labor Committee, Madden got to know Congressmen John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon. At the time, the Republicans controlled the House and passed the Taft-Hartley Bill, which Madden thoroughly opposed. As to the two future presidents, Madden said, “If anybody had told me they’d be running for president I’d have said that they were insane.”

For the next 30 years, Ray Madden would face few serious challenges for his seat in Congress. A bachelor, Madden devoted himself completely to the job and was known for providing good constituent services to the people he represented. Once defeated, Madden commented philosophically, “It’s like a game of bingo, sometimes you win and sometimes you lose.”

Eventually, Congressman Madden would endure the same kind of experience as his predecessor, William Schulte. In 1972, Madden faced an aggressive challenge from state Senator Adam Benjamin, an Assyrian-American, who had been a math teacher. Benjamin pressed the congressman hard that year, but Madden eked out a win, largely through the effort of organized labor, which stubbornly stuck to the incumbent. Madden had finally risen to chair the House Rules Committee, and organized labor did not much like the thought of a conservative succeeding to the post. Ray Madden was a proven friend of labor, and the unions did all they could to reelect him in 1972.

Benjamin did not run again in 1974 as he preferred to run for reelection to the Indiana Senate instead. Once safely reelected, Adam Benjamin set out once again to run for Congress in 1976

In 1976, Ray J. Madden was 84 years old, but he seemed to be mentally acute and physically healthy. One reporter noticed the congressman looked far younger than his actual years and still had a boyish glow about his “rosy cheeks.” Still, Ray Madden was also the oldest man in Congress at the time, while Adam Benjamin was 44 years old. Ironically, Madden would outlive his successor by several years.

Congressman Madden was not oblivious to the changing times. George Allen, the famed coach of the Washington Redskins, told the congressman at a banquet a few months before the Democratic primary that he had heard Madden was in for a rough race. “And I’ll probably get beat,” Madden conceded. Allen looked over the vigorous 84-year-old congressman and replied, “If you do, come see me and we’ll suit you up with the Redskins.”

When defeat came, it was largely due to the incumbent’s age and Benjamin won going away. Organized labor, which had supported Ray Madden throughout his long political career, seemed to realize there was little use in waging an all-out campaign to retain the congressman. Madden also believed Benjamin had been funded by the oil interests who still resented his having bucked the Democratic leadership to convince the Democratic Caucus to instruct the Rules Committee to allow amendments repealing to oil depletion allowance when certain tax legislation came to the floor. “Knocking out the depletion bonanza in the Rules and Caucus could go down taxwise as the greatest victory any congressman has,” Madden told a journalist after his defeat in 1976. The closure of the loophole cost the oil companies an estimated $2.5 billion annually. Congressman Madden thought the oil lobby was the most powerful in Washington, D.C., at the time.

Congressman Ray Madden was also somewhat bitter about his having appointed Adam Benjamin to West Point, feeling the younger man had little gratitude for his benefactor. After taking office, Benjamin announced he intended to show his appreciation to Madden by buying the former congressman a ticket to the Army-Navy game the following November. Madden retorted he intended to lobby his former colleagues to abolish the service academies, such as West Point.

Madden’s attitude had not changed as he was packing up his office when a visiting newspaper reporter stopped by. “On Jan. 3 the chairman of the most powerful committee in Congress will not be there,” Madden told the reporter, “But you’ll have a freshman starting in.

“That was quite a bargain you won May 4th,” the old congressman added sarcastically.

The congressman was ready for the winter, nattily attired in a black homburg and a black cashmere topcoat with a colorful scarf casually tossed around his neck. The injuries inflicted during the last primary campaign were apparently still rather raw. Madden made a reference to the “dummy over here in city hall,” meaning Hammond Mayor Edward J. Raskosky, who had switched his support from the incumbent congressman to Benjamin three days before the election. Emphasizing his point with a finger jabbing the air, Madden growled, “Wait until he (Raskosky) starts into his next campaign, I’ll have something to say about him.”

Without a wife and children to go home to, Ray Madden was at loose ends once his term in the House of Representatives expired in January of 1977. Many of his longtime supporters and friends back home in Indiana had become inactive or had died. Madden’s life had become the House of Representatives. The former congressman remained in Washington to be close to the action. As a former Member of Congress, Madden was entitled to certain privileges reserved for ex-congressmen, including access to the House gym, which the Indianan used daily. Madden continued to live in his apartment at the Methodist Building, a popular place for national legislators to live.

Madden had spent some time traveling during the winter months, visiting various nephews and nieces in California, noting it rained every day he was in the Golden State. Madden went from California to the Sunshine State of Florida. Ben Cole, the Washington correspondent for the Indianapolis Star, marveled there was “still a lot of red in” Madden’s hair and noted “he walks like a young man” at 85 years. Cole had caught Madden as the former congressman was “strolling across the Capitol grounds” one day.

The former congressman likely found some comfort in the presence of his grand-nephew and namesake, Ray J. Madden III, who lived with his wife in Crystal City, Virginia. The younger Maddens invited Uncle Ray and another former member of the House of Representatives, Republican H. R. Gross of Iowa, to dinner. The two, who had rarely agreed on anything while serving in the House together, had a delightful time regaling the young couple with political yarns and tales from the halls of Congress.

Ray Madden also returned to Indiana for a visit to the statehouse where the former congressman was invited to make a few remarks. After giving legislators a dose of the “famed Madden oratory” the ex-congressman enjoyed a reunion with some of his old friends in the corridors of the statehouse. The old lawmaker was given a standing ovation by state legislators when he first approached the podium to speak.

Ostensibly, Madden was supposed to be practicing law in Washington, but he was eligible to draw the maximum pension allowed a former Member of Congress, which was based upon length of service. Madden still had time to appear at Indiana University Northwest, where he lectured on the legislative process and Congress.

At age 86, Madden was asked if he missed the House of Representatives. “Hell no!” the ex-congressman barked.

Madden’s youthful successor died of a heart attack in 1982; he was only 47 years old. Ray J. Madden lived until 1987, dying at the age of 95.

© 2024 Ray Hill