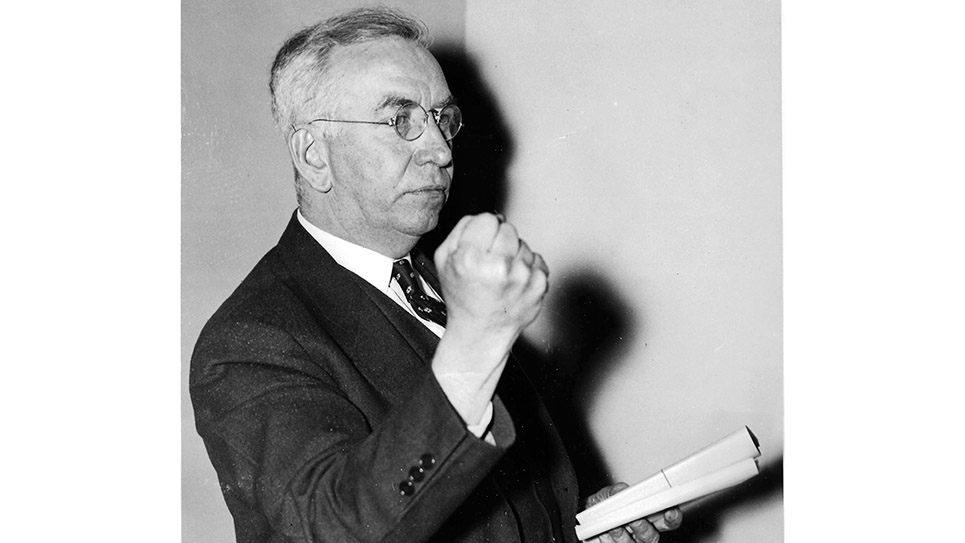

The Gentleman From Ohio: Martin L. Sweeney

By Ray Hill

Martin L. Sweeney may not have served as long as many of his colleagues in the House of Representatives, but folks knew he was there when he was a member. For twelve years, Sweeney represented a district in Cleveland, Ohio. Some viewed Martin Sweeney as “a dour, bitter-spoken individual.” It seems fairly certain Sweeney was not especially well-liked by his colleagues and once was the loser in a fistfight with a fellow congressman. There was no doubt Sweeney was plain-spoken and, as the Cincinnati Enquirer once noted, “one of the outstanding individualists in Congress.”

A man of great determination, Martin Leonard Sweeney began working at 12 to support himself while attending St. Bridget’s Parochial School. That same work ethic helped him through both college and law school, working as a construction worker and longshoreman at various times. Even before he had graduated from the Cleveland Law School, he won a seat in the Ohio House of Representatives in 1912, serving one term. Sweeney passed the bar exam and was admitted to practice law in 1914.

In 1923, Martin L. Sweeney was a municipal judge in Cleveland. As outspoken as he was determined, Sweeney did not hesitate to have his say about prohibition while serving on the bench. Judge Sweeney was strongly opposed to prohibition. During the 1932 Democratic National Convention, Sweeney attended as a delegate pledged to the candidate who was most strongly against prohibition: former New York governor and 1928 Democratic presidential nominee Al Smith. Once at the convention, Sweeney switched to support Franklin D. Roosevelt, which caused a break with his patron, Burr Gongwer, the Democratic boss of Cuyahoga County.

Gongwer, the chairman of Cuyahoga County’s Democratic Party, had helped Martin Sweeney get elected to Congress when Sweeney won a 1931 special election after Congressman Charles Mooney died. Sweeney represented an overwhelmingly Democratic district in the House of Representatives. Eventually, Sweeney managed to repair his working relationship with Burr Gongwer, if not their former friendship. Gongwer was overthrown as party chairman by Ray Miller, who promptly sponsored Michael Feighan against Congressman Sweeney in the 1940 Democratic primary.

Once in Washington, D.C., Martin Sweeney did not endear himself to many of his colleagues when during a debate on the subject of prohibition he scolded them and told them they were “behaving like a lot of old women” as far as that issue was concerned. Nor did Sweeney parse out his language. The congressman called the prohibition law “a crazy law, enacted by fanatics, impossible to enforce …” Although he had vocally disagreed with the law, he adhered to it while sitting as a judge, fining those bootleggers who appeared before him and were found guilty. Sweeney’s opposition to prohibition was the centerpiece of his campaign for the House of Representatives in the 1931 special election, as the candidate ran on a platform of repealing the Eighteenth Amendment. Evidently, most of his constituents agreed with his assessment of prohibition as Sweeney won overwhelmingly. Safely reelected to the House in 1932, Sweeney ran for mayor of Cleveland against Ray Miller and lost the primary in 1933.

When Britain’s reigning monarchs, King George VI and his queen, visited the United States and the British Embassy held a reception, it became the social event of the season in 1939. Yet Martin L. Sweeney denounced the monarchs while they were visiting, which even many who shared Sweeney’s dislike of the British Empire thought needless and rude.

Deeply angry about the arrest of Sean Russell, chief of staff of the Irish Republican Army, Congressman Martin L. Sweeney was one of 75 members of the House of Representatives who were both of Irish heritage and enraged about Russell’s being taken into custody. Even though Russell had been released on bond and ordered to report for a hearing, some threatened to boycott the reception for King George and Queen Mary. Martin Sweeney went a step further, sending a telegram to the British monarch reminding the king that Great Britain still owed the United States $5.5 billion in war debts from the First World War. Congressman Sweeney read his telegram to King George to his colleagues in the House, which included asking, “. . .do you not think it is the decent thing to give some consideration to the obligation you owe the United States of America, whose assistance in the last World War made possible the continuance of Your Majesty’s government as a world power.” Sweeney’s reading of his telegram to the king was roundly applauded on the Republican side of the aisle.

Martin Sweeney’s opinions of Great Britain were not markedly different from many of his fellow lawmakers whose parents and grandparents hailed from Ireland. As president of the Ancient Order of Hibernians, Sweeney was more than accustomed to making rabidly anti-British speeches. Yet when the House of Representatives was asking President Roosevelt to extend the condolences of the House to the people of Britain when King George V died, Sweeney came barreling out of the cloakroom screaming for the speaker’s attention. Joseph Byrns of Tennessee ignored him, called for a voice vote and gaveled through the resolution as having passed.

Congressman Sweeney, with a true Irishman’s hatred for Great Britain, sat down on the floor next to Representative Beverly M. Vincent of Kentucky. Vincent bluntly told Sweeney he wished the congressman from Ohio would sit elsewhere. When the Ohio congressman took umbrage, Vincent barked Sweeney was a “traitor” and “a son-of-a-bitch.” That caused Sweeney to take a swing. With “obvious satisfaction,” Vincent “planted a good hard right” which “staggered and silenced” Sweeney. An “ancient” doorkeeper chuckled it was one of the most satisfying punches ever thrown during his time as an employee of the U.S. House of Representatives.

Congressman Martin Sweeney’s fierce opposition to American intervention was attributed to his hatred for the British. Sweeney’s isolationism was hardly less pronounced after the Japanese had attacked Pearl Harbor. Neither President Roosevelt nor the Democratic high command appreciated those fellow Democrats who questioned the conduct of the war. Things were not going well for the Allied forces during 1942, as American, British and Russian forces seemed to experience setback after setback. The Japanese gobbled up territory in the Far East while Hitler’s legions seemed unstoppable in the West. Congressman Sweeney was quite open with his criticisms of the British in particular and it was no secret the New Dealers very much would like to see him removed from the House of Representatives. So, too, did the daily newspapers decide to rid Cleveland of Martin Sweeney from the halls of Congress. Louis Seltzer, editor of the Cleveland Press thought Sweeney an embarrassment to the city and state and began a crusade to beat the congressman. The Plain Dealer and the News joined in, pounding Sweeney’s record in Congress.

Ray Miller sponsored Michael Feighan’s candidacy yet again in the 1942 Democratic primary. To the surprise of no one, Feighan ran as an all-out supporter of President Roosevelt and on a platform of winning the war and support for America’s allies. Congressman Sweeney and challenger Michael Feighan waged what one local newspaper referred to as a “torrid” fight inside the Democratic primary. Feighan charged Sweeney with being the “leader of isolationism in northern Ohio and always a welcomed speaker at local German-American bund gatherings.” Sweeney, incensed, retorted, “If I was connected with Nazi propaganda, take me to jail and indict me. Then prove the charge. That’s the American way.”

Many Americans bitterly resented Sweeney’s attitude with the war not going well for the Allies and Michael Feighan beat Congressman Martin Sweeney handily. Several other prominent Democrats openly endorsed Feighan over Sweeney, including Cleveland Mayor Frank J. Lausche. Sweeney lost by an almost two-to-one margin but was unrepentant, saying, “They attacked my record in Congress because I refused to vote for measures which, I was sure, would involve the United States in foreign wars. I prefer to let time and history vindicate my position.” On a more bitter note, Sweeney blamed his loss on “a combination of newspapers, Communists and misguided persons.”

There were other members of Ohio’s congressional delegation labeled as “isolationists” who were not defeated. In fact, no less than fifteen members of Ohio’s congressional delegation were identified as isolationists by the New Republic and press lord Henry Luce, whose TIME magazine was the premier news magazine of its day and read each week by millions of Americans. Luce was an ardent internationalist, and his publications were caustic critics of those who were non-interventionists. Martin L. Sweeney was the only Member of Congress from Ohio to lose his primary campaign who had opposed many of the Roosevelt Administration’s defense policies prior to the bombing of Pearl Harbor by the Japanese. The failure to oust other pre-Pearl Harbor isolationists from Congress caused the Dayton Herald to state the “Pre-War Isolationist Issue Smashed. . .” with all incumbents renominated except for Martin Sweeney.

Martin L. Sweeney was not done with politics and whether it was motivated by revenge, or because he genuinely believed he could win, the former congressman ran for mayor of Cleveland in 1943 and lost to Frank Lausche. The following year Sweeney waged a quixotic bid for the Democratic nomination for governor. The hugely popular incumbent, Republican John W. Bricker, was the GOP vice-presidential nominee and not running again. The front-runner for the Democratic nod was Sweeney’s political nemesis and mayor of Cleveland, Frank J. Lausche. Six candidates competed for the nomination, but the momentum was heavily weighted toward Lausche. While Martin Sweeney ran second, he was more than 115,000 votes behind Mayor Lausche. Still, the powers that be in Ohio were stunned by Martin Sweeney’s second-place finish.

The loss of the Democratic nomination for governor was hardly the last card Martin Sweeney had up his sleeve. The former congressman announced he had joined the “American Democratic National Committee,” which was an anti-Roosevelt group composed of defecting Democrats. Sweeney was supporting the GOP ticket of Thomas E. Dewey and John W. Bricker. “We feel that rural Ohio is already solidly Republican,” Sweeney told a reporter. “A great number of Jefferson Democrats” would likely join the movement in Ohio. “When Browder and Hillman (a Communist and labor leader, respectively) crawl into the Democratic party, it is time for Jeffersonian democrats to walk out,” Sweeney said.

FDR lost Ohio to Dewey and Bricker, largely because of John Bricker’s personal popularity in the Buckeye State. Without Bricker on the ticket four years later, Dewey lost it to Harry Truman.

Martin Sweeney’s last political race was a nonpartisan race in a special election to fill a seat on the Ohio State Supreme Court. The former congressman polled only 9,440 votes, while the winner, Henry A. Middleton, garnered more than 282,000. It was then Sweeney realized politics was done with him.

Sweeney contented himself to return to his law practice with his son, Robert. The fiery former congressman remained active until the end of his life. With his final defeat for elective office and failing to gain a seat on the Ohio State Supreme Court, Martin Sweeney settled down into a law practice with his son Robert. On Sunday morning, May 1, 1960, Marie Sweeney went upstairs to wake her husband to start getting ready to go to church. Mrs. Sweeney discovered her husband wasn’t breathing and had died sometime during the night.

Robert Sweeney followed his father onto the bench as a municipal judge in Cleveland and into the U.S. House of Representatives, serving a term as congressman-at-large from 1965-1967. Sweeney was a strong supporter of President Lyndon Johnson’s program during his two years in Congress. His father’s law partner until Martin Sweeney’s death, Bob Sweeney became a millionaire due to his asbestos lawsuits, after having found evidence of the manufacturers knowing it was dangerous and allegedly hiding it. Father of thirteen children with his first wife, Robert Sweeney died June 30, 2007.

© 2024 Ray Hill