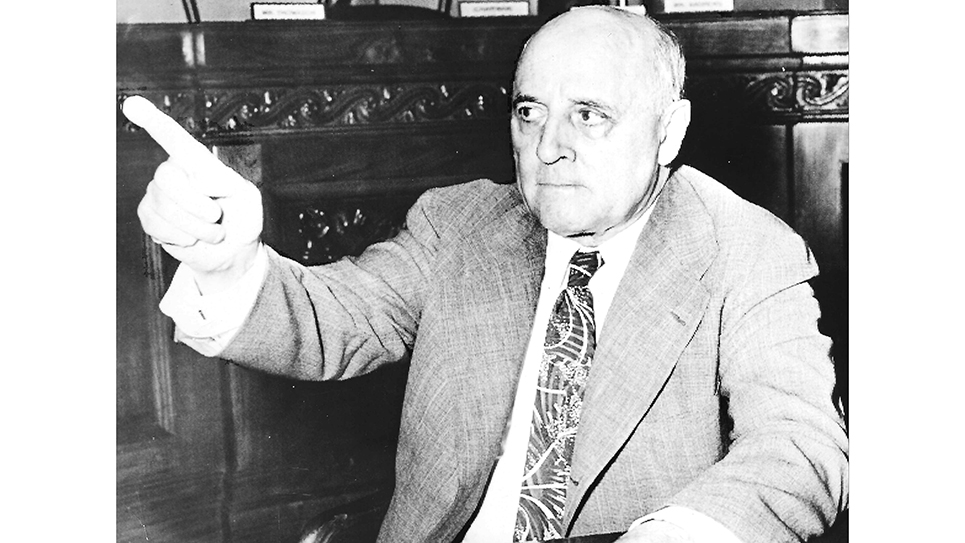

The Gentleman From Oregon: Rufus Holman

By Ray Hill

Oftentimes the success of a candidate for public office has as much to do with the particular times, the mood of the public at a given moment. One of the advantages of being a United States senator is the length of a single term, six years. Yet in the passage of that time, the mood of the electorate may well have changed. The ebb and flow of thought explain many political careers, their beginnings and especially their ends. It also explains the election of Rufus Cecil Holman to the United States Senate, as well as his departure.

In 1938, the threat of war hung over the United States like a malignant black cloud. War clouds gathered across the world with the ferocious and bloody conquest of China by the Japanese Empire while war threatened to break out at any moment in Europe due to the territorial ambitions of German dictator Adolf Hitler, as well as the pretensions of Hitler’s ally, Italian dictator Benito Mussolini who had visions of recreating the Roman Empire. The First World War was still fresh in the minds of millions of Americans who objected to the idea of American involvement in another foreign war. One of the most powerful blocs in Congress was that of noninterventionists, labeled isolationists by the media. The most widely read news magazine of its day, TIME, was published by Henry Luce, a strong supporter of an international outlook for American foreign policy. TIME employed some of the best news writers anywhere and they excelled in the use of adjectives hurled with special glee and venom toward any politician who was not an avowed internationalist. When Rufus Holman lost in 1944, TIME described the senator as “an isolationist, a party hack, a reactionary, a labor baiter.” TIME also noted Holman was “big of girth, white of hair, loose of lip” whose most stellar achievement while in office, at least according to TIME, was having missed 148 out of 239 roll call votes during seven months of 1942. The writer for TIME gleefully described the senator’s voice as a “gravelly falsetto” which the Oregon Journal enjoyed calling Holman’s “high tenor of protest.” It was certainly true that Senator Holman was woefully uneducated about geography and some aspects of English. When accused of being antisemitic, Holman cried, “Now why would I be antisemitic? My own father was an Englishman. I have relatives in England.”

Holman was oftentimes described as “flamboyant” and one of the more “colorful” of Oregon’s politicians. Despite his occasional ill-phrasing, Holman was usually an eloquent and capable speaker.

Rufus C. Holman had been the son of parents who traveled across the plains to settle in Portland. Holman was raised on a farm and, following graduation from high school, he became a successful businessman. Holman worked as a clerk, accountant, and auditor before becoming a partner in a book-binding business and the owner of the Portland Paper Box Company, which manufactured cardboard boxes. Like many successful businessmen, Holman took time to volunteer for civic service to his own community. Holman occupied various posts in both municipal and county governments.

When he was appointed state treasurer for Oregon, Holman was chairman of the Multnomah County Commission. Holman won the election in his own right and made a bid for the GOP nomination for governor in 1934 and while he made a respectable showing, he lost the election. Rufus Holman ran for reelection as state treasurer in 1936 and won. Holman’s 1938 campaign was his fourth statewide effort in four years, giving him good name recognition in Oregon. Holman won the 1938 GOP primary, handily turning back a bid by former Senator Robert Stanfield, who was involved in a drunken bar fight in the midst of prohibition and never again elected to public office despite several attempts to return to Congress. Once nominated, Holman easily defeated Democratic candidate Willis Mahoney, who had quite nearly toppled Oregon’s most popular elected official, Senator Charles McNary, two years earlier. Rufus Holman carried every county in Oregon to win election to the U.S. Senate.

Once in the U.S. Senate, Holman venerated the institution. Deeply proud of his membership in the most exclusive lawmaking body in the world, Rufus Holman was respectful of the Senate and its customs and traditions. On those days he knew he would rise on the floor and speak, he donned a formal, swallow-tailed coat. Holman was assigned to the Military Affairs Committee, which boasted several prominent noninterventionists among its members. While many considered Rufus Holman to be profoundly conservative, he was also a strong supporter of public power projects. Holman’s original appointment as Oregon’s State Treasurer came at the hands of Governor Julius Meier, who was quite liberal.

In February of 1944, President Franklin D. Roosevelt kicked off his third reelection campaign by sending a message to Congress battering the Soldiers’ Voting Bill, which had been passed by the Senate the previous December. The bill left it up to the individual states as to the matter of voting. The president accused the House and Senate of having attempted to perpetrate a “fraud on the soldiers and sailors and marines” as well as “on the American people.” Roosevelt insisted the solution was a ballot provided by the federal government. Two Senate Democrats, Theodore Francis Green of Rhode Island and Scott Lucas of Illinois, had just such a bill, which was co-sponsored by Congressman Eugene Worley, a 29-year-old then serving as a lieutenant commander in the U.S. Navy. The members of the United States Senate heard the president’s message in icy silence. Roosevelt believed the matter deserved a roll call vote and slyly suggested in his message every congressman should be glad to “stand up and be counted.” FDR disingenuously said he was well within his rights in making his suggestion “as an interested citizen.” That sentence brought “mocking laughter” from a seething House.

Senator Rufus Holman, after listening to Roosevelt’s message, blurted, “It seems to me that the difficulty centers around the fact that the Commander in Chief of the Army is himself a candidate for the presidency. If he would eliminate himself from that advantageous or unfair position, I think debate on the pending bill would cease.”

That brought a quick reply from Senator Abe Murdock of Utah, a Democrat. “I know it is the prayer in his heart, and it is the prayer in the heart of every other good, old, stand-pat Republican in the United States today,” Murdock said, “that Franklin D. Roosevelt would eliminate himself from politics and give them at least the shadow of a chance to bring in the Grand Old Party again. But I say to them … the American people still want Roosevelt.”

Holman was challenged inside the Republican primary by Wayne Morse, a 43-year-old former dean of the University of Oregon’s law school. Morse had been appointed to the National War Labor Board in 1942 and served until his resignation in 1944. Remembered by historians for his liberalism, Morse campaigned in 1944 as a solid conservative, denouncing the New Deal in acidulous terms. It was only after his election Morse revealed he had voted for Franklin Roosevelt over GOP presidential nominee Thomas E. Dewey in the 1944 election.

Holman, an Old Guard Republican, made no pretense about his own views and campaigned on the record he had made in the United States Senate. Holman flatly stated Wayne Morse had been prompted by the Roosevelt Administration to challenge him inside the GOP primary. As to his view of Roosevelt’s foreign policy, Senator Holman told the audience at one chamber of commerce dinner, “The fact is that I have never denied being an isolationist; nor have I ever denied being a Christian, or a patriot – – – nor have I ever denied that I put the welfare of the American people above that of any other people.” Holman reviewed his own record and blamed FDR personally for the failure to protect the American fleet at Pearl Harbor. Senator Holman said the president “was so busy with his international friends in Europe” that Roosevelt did not see the exposure of the fleet in Hawaii. “Franklin D. Roosevelt was the most responsible person in America for the disaster at Pearl Harbor,” Senator Holman insisted.

Wayne Morse’s defeat of Rufus Holman was considered a major upset of an incumbent senator. Walter Winchell, a gossip columnist with a regular newspaper column in hundreds of daily newspapers as well as a national radio program with an audience in the millions, declared the election win of Wayne Morse a “Roosevelt victory” and accused the candidate of being a New Dealer. That nettled Morse who said it was a Republican victory. Morse promptly fired off a telegram to Winchell saying he “strenuously objected” to the columnist’s description of his primary win. Morse said his own win as an opponent of the New Deal was the “forerunner to a nationwide republican victory over the New Deal administration next November.” A curious thing for one to say who later admitted to voting for FDR. Morse was one of the very few Republican senators who strongly opposed the Taft-Hartley Act. Later Wayne Morse would leave the Republican Party to become an Independent and then a Democrat.

Not surprisingly, Rufus Holman was both hurt and bitter at his primary loss. The senator told friends his defeat was the result of “money and a smear campaign against me.”

There was perhaps some salve for Senator Rufus Holman following his defeat in the 1944 Republican primary. That summer Holman, a widower, wed Mrs. Norma Lundeen, the “comely widow” of the late senator from Minnesota who had been killed in a mysterious plane crash in 1941. If anything, Lundeen had been more rabidly noninterventionist than Holman, so much so that some claimed the Minnesota senator was a Nazi sympathizer. Apparently, it was a happy match, as the couple remained married until the former senator’s death.

Rufus Holman and Norma lived a comfortable life in Portland, Oregon. Holman tended to his business interests and would occasionally send a note to Senator Richard Neuberger written in his own hand, offering the Democrat advice on issues of importance to Oregon and her people. Holman’s notes were written on Senate stationery, which was provided to the former senator by Neuberger annually.

One of the great pleasures of Rufus Holman’s later life was his recognition by Governor Robert Holmes, a Democrat. Holmes presented Holman with the state’s highest military award, the National Guard Distinguished Service Medal, at Camp Clatsop. The 81-year-old former senator was delighted.

The 82-year-old former senator had been suffering from a heart ailment, which had caused him to be treated at a local hospital. Yet the coroner was not certain as to the cause of death for Holman. Lane County Coroner Fred Buell said the former senator died from either a heart attack or from a fall down ten steps to the basement. Evidently, Holman had mistaken the door for that leading to a closet. Holman had died in the house of his stepson, Ernest Lundeen Jr., where he and his wife had gone to visit for the Thanksgiving holiday. Lundeen and his wife were out when the former senator fell. Eventually, Mrs. Holman heard a groan and she descended into the basement where she found her husband. Mrs. Holman rushed upstairs and called the doctor, who found the former senator dead when he arrived.

Following the former senator’s death, one admirer, Frank K. Haskell, wrote a letter to the editor of the Eugene Guard, lamenting the passing of “our friend.” Haskell wrote Holman had not been an isolationist “for there is just no such thing.” Rather Rufus Holman, according to the writer, was a man “who loved his country and held to that idea, even though he was turned down by ignorant voters to serve in the United States Senate.”

© 2024 Ray Hill