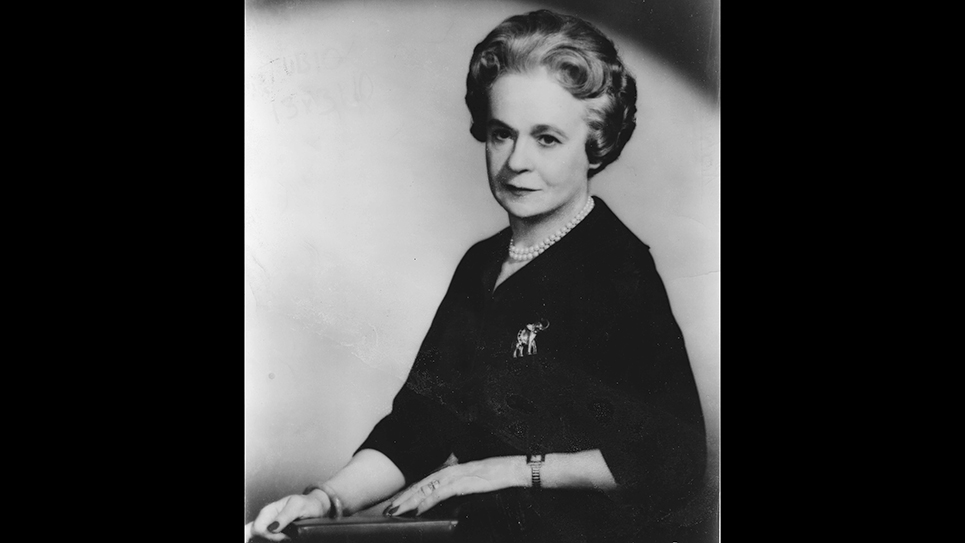

The Gentlewoman From Tuxedo Park: Katharine St. George

By Ray Hill

For a time, Katharine Price Collier St. George was the First Lady of a swath of upstate New York ranging from her home in Tuxedo Park to Delaware County. That title came not from her pedigree, which was perfect, nor was it because of whom she married. It was a title she earned through her own efforts and abilities. For eighteen years, Katharine St. George represented her people in the U.S. House of Representatives. During her time in the House, Mrs. St. George was one of the more recognizable faces of Republicans in the House. Katharine St. George served in Congress at a time when a woman’s place was more in the home than the House of Representatives. Katharine St. George was the first woman ever to sit on the powerful House Rules Committee, which determined what bills reached the floor. Congresswoman St. George was also a firm supporter of rights for women. Benjamin Gilman, a successor in the House, recalled “it was through her efforts that the first hearing was held on the Equal Rights Amendment in the Congress.”

Tuxedo Park was famous as the first haven for millionaires. The name was derived from men’s dinner jackets, which had become popular with society folks.

Today the campaigns of Katharine St. George would seem quaint, if not antiquated. Congresswoman St. George typically drove herself throughout her district to attend a never-ending series of “teas, rallies, fashion shows and women’s club meetings.” The congresswoman refused to attend debates with her opponents, snapping political debates were “asinine.”

Katharine St. George was a first cousin to President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Mrs. St. George’s mother, Katharine, was the sister of FDR’s formidable mother, Sara Delano. Warren Delano, the grandfather of both Katharine St. George and Franklin Roosevelt, once said, “I will not say that all Democrats are horse thieves, but it would seem that all horse thieves are Democrats!”

Her father, Hiram Price Collier was a working journalist, writing for a long ago forgotten magazine called Forum. Collier and his wife, Katharine, moved to Tuxedo Park when their daughter was two years old. For the remainder of her life, it was home to Katharine St. George.

Katharine Price Collier married George St. George, the third son of the Baronet St. George. Their union produced one child, a daughter, Priscilla. Mrs. St. George was long active in her community politics before her election to Congress, having been elected as a member of the governing body for Tuxedo Park. Mrs. St. George also chaired the Orange County Republican Party from 1942 until 1948 and was a delegate to the 1944 National Convention which selected New York Governor Thomas E. Dewey as its presidential candidate. When they had first met, George St. George was working as a clerk for J. P. Morgan and Company. George St. George later was the owner of a coal brokerage while his wife acted as vice president, secretary and treasurer of the company. Katharine St. George loved dogs and was well known for breeding prize English setters and pointers. At one time, Mrs. St. George was the president of the English Setter Club of America.

Katharine St. George had diminished her political activity somewhat when her cousin Franklin Roosevelt was elected president in 1932. When FDR sought an unprecedented third term, Mrs. St. George reentered politics more determined than ever before. Having supported numerous candidates up and down the ballot for years, for the first time Katharine St. George began to think of becoming a candidate for public office herself. Mrs. St. George wanted to be elected to the New York State Assembly. The opportunity to run for office came in 1946 and it was for the U.S. House of Representatives rather than the New York State Assembly.

To get to Congress, Katharine St. George had to take on an incumbent inside the Republican primary. August W. Bennett’s own path to the House of Representatives had been a circuitous one. New York’s Twenty-Ninth Congressional District was heavily Republican and had been represented in the House by fire-breathing nationalist Hamilton Fish since 1920. Fish was a determined foe of internationalism and the New Deal. Ironically, Fish represented the district in which Franklin Roosevelt lived. Congressman Fish was one of the most disliked members of Congress by those who were internationalists, who were well represented in the news media of the time. Henry Luce, a powerful publishing magnate whose empire included both LIFE and TIME magazines, was especially critical of those congressmen and senators who were identified by opponents as isolationists. Even with the relentless opposition of much of the news media, the White House and Eastern financiers, Hamilton Fish continued to be reelected. It took Governor Thomas E. Dewey, the boss of GOP politics in the Empire State, to redraw Fish’s district to beat him at the polls. Augustus Bennett faced off against Congressman Fish inside the Republican primary and lost. Bennett was also on the ballot in November as a Democrat and won the general election.

The son of a congressman, August Bennett sought to win reelection in 1946, running as a Republican. TIME magazine followed the primary campaign, describing Katharine St. George as “trim, glib, tireless” while Congressman Bennett was dismissed as a “colorless” attorney. TIME noted the “chic” Katharine St. George “awed her constituents.” Mrs. St. George traveled throughout the four-county congressional district by driving 200 miles daily, meeting at least 75 people each day. Katharine St. George ate with Republican leaders throughout the four counties and “spoke every other night.” “Her platform vibrated with promises of jobs and homes for veterans, hope for farmers and love for labor’s hard-won gains,” TIME’s correspondent wrote. Mrs. St. George also campaigned for relaxing or eliminating government control over much of business as the Second World War had ended. Katharine St. George also promised to support strengthening America’s foreign policy as a member of congress.

“One good thing about women in politics is that they are not continually comparing themselves to the Great Emancipator,” Katharine St. George quipped.

As might be expected, former Congressman Hamilton Fish, still had thousands of friends and supporters inside the district. Never one to hold his tongue, Fish was fully behind Katharine St. George’s candidacy. TIME, which had been highly critical of Fish, finally acknowledged that “down in the bottom of its heart, the 29th district still liked Ham.” Moreover, the news magazine thought Mrs. St. George to be “politically irresistible.”

“Nobody can pin a Fish label on me,” Katharine St. George insisted. “Ham Fish would support a wooden Indian against Bennett.”

Katharine St. George carried three out of the four counties to win the Republican primary decisively. Mrs. St. George beat her Democratic opponent in the general election easily. For the next 18 years, she would routinely dispatch her Democratic opponents, which included Pulitzer Prize-winning cartoonist Bill Mauldin. Mauldin campaigned throughout the district by jeep and airplane, which was a novelty at the time. Katharine St. George beat the cartoonist with better than 62% of the votes cast.

Katharine St. George applied herself and began rising through the ranks of the House GOP rapidly. Congresswoman St. George focused her Washington office on serving the people of New York’s Twenty-Ninth District and she studied the rules and procedures of the House of Representatives. Katharine St. George’s knowledge of those oftentimes intricate rules and procedures was recognized by her party when she was made the first female parliamentarian in the history of the Republican Party to preside over a national convention in 1956. The congresswoman’s deft handling of situations arising from the floor of the convention and her thorough knowledge of the rules was impressive at a time when the conventions being broadcast live over national television was still something of a novelty. Katharine St. George was the parliamentarian again in the 1960 and 1964 GOP national conventions.

During her last year in Congress, Katharine St. George tangled with Howard W. Smith of Virginia, the old country judge who chaired the House Rules Committee, over the civil rights bill pending before Congress. When Smith offered an amendment to the civil rights bill which would have effectively banned “discrimination by reason of gender as well as race,” the judge opined, “This bill is so imperfect, what harm will this little amendment do?”

“Nothing could be more logical,” Congresswoman St. George retorted. “We outlast you. We outlive you. We nag you to death. We want this crumb of equality. And the little word ‘sex’ won’t hurt the bill.”

Defeat came in 1964. As is usually the case when a longtime incumbent loses, the cause was a combination of reasons. 1964 was one of the worst years ever for Republicans in the Empire State. It was nothing less than a complete debacle for the Republican Party. New York Republicans were generally not as far to the right as GOP presidential nominee Barry Goldwater and there was a visceral and negative reaction to the Arizonan’s nomination. Lyndon Johnson won quite nearly 70% of the votes cast in New York, while Goldwater polled just over 31%. The size and scope of the defeat reverberated down the ballot. Senator Kenneth Keating lost to carpetbagger Robert F. Kennedy and Katharine St. George lost narrowly to liberal Democrat John G. Dow. The Johnson landslide was one big reason for Congresswoman St. George’s defeat, but there were other factors involved as well. Carmen Freda, chair of the Rockland County Republican Party, remembered the congresswoman was more vulnerable “because she ended up spending a lot of time in Washington and losing touch with her district.” Freda still insisted Katharine St. George had been “a terrific congresswoman.” “I think what set her apart was that she stood firm on her conservative principles, the things she believed in, no matter what,” Carmen Freda told a reporter. “She was a great lady. We’re not going to see another one like her again.”

Leaving the House of Representatives in 1965, Katharine St. George went home to Tuxedo Park. Mrs. St. George became a member of the board of trustees for Americans for Constitutional Action, the counterpart to Americans for Democratic Action. Seventy-one years old at the time of her defeat, the former congresswoman made it plain she would not entertain the thought of a comeback campaign in 1966. Katharine St. George did state she intended to have a say in selecting the GOP nominee to face Congressman John Dow in 1966. Dow managed to win reelection that year, but St. George had not forgotten her defeat. In 1968, she paid for newspaper ads urging voters to support Martin McKneally for Congress. The two faced one another again in a 1970 rematch election and that contest was won by John Dow. Following redistricting in 1970, Dow had to run in a slightly different district in 1972 and lost to Benjamin Gilman. Dow made three attempts to return to the House of Representatives in 1974, 1982 and 1990 when he was 85 years old.

The former congresswoman was a staunch supporter of Ben Gilman. In 1973, Katharine St. George was among those who attended a testimonial dinner honoring former Congressman Hamilton Fish. Fish’s son and namesake, Hamilton Fish Jr., was at the time the congressman for parts of the district once represented by both his father and Katharine St. George. Mrs. St. George was a member of the dinner committee, which included U.S. Senator James L. Buckley of New York and James A. Farley, one-time chairman of the Democratic National Committee and Postmaster General of the United States under Franklin Roosevelt. It had been quite nearly 30 years since Fish had left Congress and it is remarkable a former official was honored so many years after leaving office.

Katharine St. George remained an active Republican following her retirement from Congress and continually gave of her time and money to causes and charities in the community where she had lived almost literally her entire life. At some point in time, Mrs. St. George had pared down her age in her biographies and when she died in 1983, she was 88 years old instead of 86 as reported in most newspapers of the time. © 2024 Ray Hill