The Last Campaign: Overton vs. Orgill

The story of Samuel Watkins Overton is as interesting as it was turbulent. Overton came from one of Tennessee’s most aristocratic families; his great-great-grandfather John Overton was one of the Volunteer State’s most distinguished citizens. John Overton was one of the founders of Memphis; in fact, it was John Overton who owned the forest which was cleared to build the City of Memphis. Watkins Overton was also the maternal grandson of Napoleon Hill, one of the most notable and wealthiest individuals in Memphis. Hill, no relation to the “self-help” author of the same name, became wealthy as a partner in a cotton and wholesale grocery business. Napoleon Hill became president of the Cotton Exchange in the Bluff City and was one of the owners of the first streetcar systems in Memphis. Hill invested money in the steel industry in Birmingham, Alabama as well as the Union and Planters Bank, which became Union Planters.

The enormous wealth accumulated by Napoleon Hill was evidenced by his spectacular home built in downtown Memphis, a mansion built in the baroque style of the French Renaissance style of architecture. It was said when Hill died his was the largest estate in Tennessee.

Watkins Overton possessed an impeccable pedigree coming from two very wealthy and notable families. The income from vast real estate holdings made it unnecessary for Watkins Overton to work, yet he became an attorney, joining the law firm founded by Kenneth D. McKellar, then serving his first term in the United States Senate following six years of service as the congressman from Shelby County.

No one ever accused Watkins Overton of being lazy; quite the contrary, Overton was known for working hard at his job and his diligence. By 1924, Overton had been noticed by Edward Hull Crump, leader of the Shelby County political organization. Crump sponsored Watkins Overton as a candidate for the Tennessee House of Representatives. Two years later, Overton was elevated to the State Senate. Crump had yet to fully consolidate his political power inside Shelby County, which he hoped to do in the 1927 mayoral election. Crump backed Watkins Overton to challenge incumbent Rowlett Paine. Following a hard-fought and bitter campaign, Watkins Overton eked out a narrow victory. From that time until his death in 1954, E. H. Crump was the master of Memphis politics. One good reason for Crump’s influence in city elections was the record built by Watkins Overton. To this day, many consider Overton to have been the greatest mayor the City of Memphis ever had. Mayor Overton’s accomplishments still dot the landscape of the city. Watkins Overton was the mayor during some of the most challenging of times for the City of Memphis and its people. Overton guided Memphis through the hardships of the Great Depression and was mayor when the Great Flood of 1937 inundated areas of the city. The suffering in Memphis from the Depression was considerably alleviated by the position of influence held by Tennessee’s senior United States senator, Kenneth McKellar. McKellar was the ranking member of the Senate’s powerful Appropriations Committee, the portal through which every federal dollar allocated by the government passed. Senator McKellar was much admired by not only his colleagues, but also by the people of Tennessee for his propensity to direct as many of those federal dollars as he could get to the Volunteer State. Mayor Watkins Overton worked closely with Senator McKellar in steering projects, which meant jobs for local men and women, and dollars for Memphis, which did much to help insulate the Bluff City from the worst aspects of the Great Depression.

It was the administration of Mayor Watkins Overton that righted the financial ship of the City of Memphis, turning a $900,000 deficit into a million-dollar surplus. Overton oversaw much of the development of modern Memphis, including one of the best zoos in the world at the time, as well as Crump Stadium, the Overton Park Shell, and a state-of-the-art Humane Society facility.

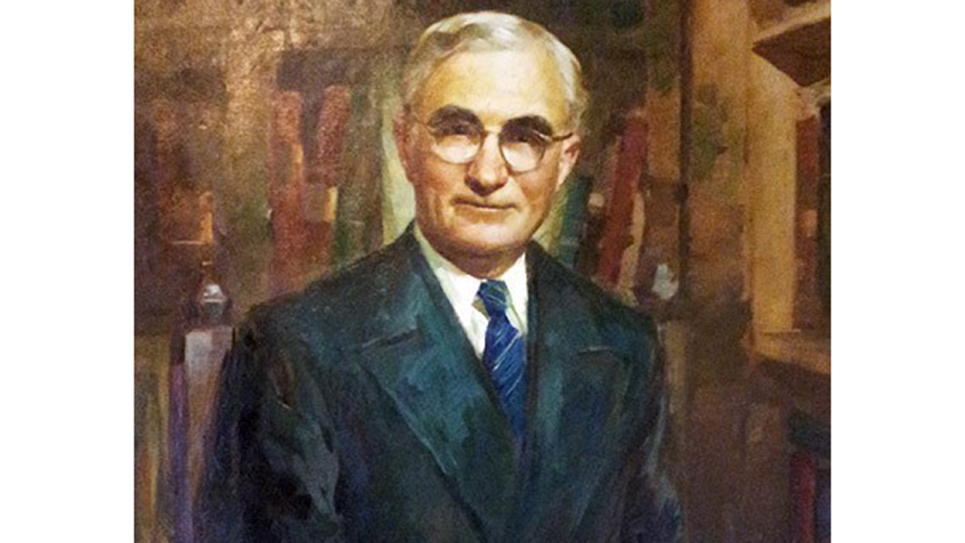

Even the Mayor’s critics readily acknowledged Watkins Overton possessed a remarkable mind for the many technical aspects of public policy, not the least of which was finance. Recognized as “a man of strong sentiments” he was also highly cognizant and sympathetic where those less fortunate were concerned. A reporter for the Memphis Press-Scimitar recalled Overton as “a man of dignity and a man of warmth and humor.” Overton was also well able to handle his end of any argument and was known for his “eloquent rebuttals to personal attacks” by political opponents.

A diminutive man, Watkins Overton was always well-dressed and exemplified the courtly Southern gentleman. E. H. Crump was not well-known for his ability to get along well with others; quite the contrary. James A. Farley, Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Postmaster Master General and chief dispenser of patronage during the New Deal, knew every important politician in the country during his heyday. Farley once said apparently the only person Crump could get along with for any extended period of time was Senator McKellar. Watkins Overton might very well have agreed with that assessment of the Memphis Boss. Overton was a determined leader with a mind of his own, a man of ability. It was quite likely the relationship between Mayor Overton and E. H. Crump would become untenable after a period of time.

Crump had shoved aside Congressman Hubert Fisher in 1930 by abruptly announcing his own candidacy for Congress that year. Fisher, who was growing increasingly deaf, wisely opted not to run again. After being reelected in 1932, the Memphis Boss decided he didn’t much like being in Washington, D.C., for half of the year. Crump owned a very successful insurance company, as well as other business interests, and found it difficult to attend to his personal affairs and disliked being away from his family. Nor did the Memphis Boss much like the idea of being only one of 435 members of the House of Representatives. In the nation’s Capitol, Crump was constantly reminded of the prestige and power of Senator McKellar and it was hardly surprising the Boss preferred to return home to Memphis where he was the dominant political figure.

In 1939, Overton and Crump fell out in a sensational disagreement over the City of Memphis purchasing the local power company. Memphis had been the first city in Tennessee to use power generated by the Tennessee Valley Authority, which provided its citizenry with cheaper electric rates. The end result of the dispute was Crump had his way and Watkins Overton resigned after serving for eleven years as mayor of Memphis. The former mayor exited the office with an emotional blast at Crump, saying he would never raise his hand in salute to any dictator.

Much of the trouble between Crump and Mayor Overton may well have been instigated, at least to some degree, by Ralph Picard, who was once described as “a brilliant and vigorous young newspaper reporter” who had joined the administration in 1935. Picard quickly became a confidant of the Mayor and pushed Overton to become politically independent of Crump. Ralph Picard had political designs himself, working with Overton to create the Council of Civic Clubs and organizing a strong and vibrant Young Democratic Club of Shelby County. Picard saw himself as building his own political organization to replace that of the Crump machine.

Following Watkins Overton’s exit from the mayor’s office, Ralph Picard waged a quixotic bid for Congress in a 1940 special election to fill the seat of former congressman Walter Chandler who E. H. Crump had summoned home to serve as mayor in place of Overton. Crump backed Clifford Davis who crushed Picard. Ralph Picard left Memphis for Washington, D. C. where he was employed by the Department of Agriculture.

For a time, Watkins Overton resumed the practice of law and managing his investments and properties. In 1947, Overton was approached by Ed Crump who urged the former mayor to run for president of the city school board. Overton agreed and was elected. As usual, Watkins Overton worked hard at his new position and enjoyed something of a political reconciliation with the Memphis Boss. That rapprochement was close enough that Watkins Overton was elected mayor of Memphis once again by the City Commission in 1949 following the resignation of James J. Pleasant, Jr.

One likely reason for Watkins Overton being reinstalled as mayor was due to the defeat suffered by the Crump machine in 1948. The 1948 election represented the greatest political mistake of Ed Crump’s long political career and it was the worst defeat ever suffered by the machine. Crump had decided he would no longer support Tennessee’s junior United States senator, Tom Stewart for reelection. The Memphis Boss notified Stewart of his decision and almost certainly expected the senator to quietly retire. If so, the Memphis Boss was surprised when Stewart stubbornly announced he would be a candidate for reelection and denounced Crump roundly. Crump’s mistake was compounded by his decision to back an obscure Circuit Court judge from Cookeville, John A. Mitchell, for the Democratic nomination instead. Some Crump associates indicate the Memphis Boss was influenced by Will Gerber who had whispered Senator Stewart was antisemitic, which was untrue. Crump had never even met Judge Mitchell when he endorsed him for the U. S. Senate.

Crump’s mistake opened the door for the candidacy of Chattanooga Congressman Estes Kefauver who ran as an opponent of the machine. The contest for the Democratic senatorial nomination became a three-way affair between Senator Stewart, Congressman Kefauver and Judge Mitchell. Crump was bitterly opposed to Kefauver, who won the nomination with a plurality of 42% of the ballots cast. Mitchell carried little more than his home county of Putnam and Crump’s domain of Shelby County. Senator Stewart ran second and it was clear Crump’s backing of Mitchell had not only defeated the incumbent but had also elected Kefauver.

Likewise, the Crump machine had been defeated in the race for the Democratic nomination for governor. Crump supported incumbent Jim Nance McCord who faced former governor Gordon Browning in the primary. Browning was Crump’s most vocal critic in Tennessee, along with Silliman Evans, publisher of the Nashville Tennessean. Browning had left office in 1939 as one of the worst defeated governors in Tennessee’s history, but he came roaring back to win in 1948. Jim McCord’s defeat was less a rebuke of his support by the Crump machine than the fact he had instituted the sales tax in Tennessee. Most of the sales tax went to education and for the first time provided free textbooks to school children, but Tennesseans are notoriously opposed to tax increases irrespective of how high or noble or deserving the beneficiary of the increase might be.

The 1948 election also witnessed the first real sign of a rebellion on the part of members of the establishment in Memphis’ business and social life defying the will of Ed Crump. Congressman Estes Kefauver had received open and strong support from some of the Bluff City’s most prominent business leaders, including attorney Lucius Burch and businessman Edmund Orgill. Kefauver naturally also had the backing of perpetual Crump critic Edward Meeman, editor of the Memphis Press-Scimitar. The machine had been astounded when the ballots were counted. Judge Mitchell won with 37,771 votes and Estes Kefauver had 27,621. Senator Stewart ran a pitiful third with only 2,733 votes. Likewise, Jim McCord had easily carried Shelby County with 48,261 votes while Gordon Browning received a respectable 20,435. Clearly, the days when the machine could deliver huge majorities to its favored candidates were numbered.

The 1948 election shook the Crump machine to its very foundations and that is likely why Watkins Overton experienced a political revival. The former mayor was rather like a safe harbor for the Crump machine in a storm. Overton was a figure well known to most Memphians, a great majority of whom believed had done a good job in office previously.

For a while, the seas were calm. It was not to last.