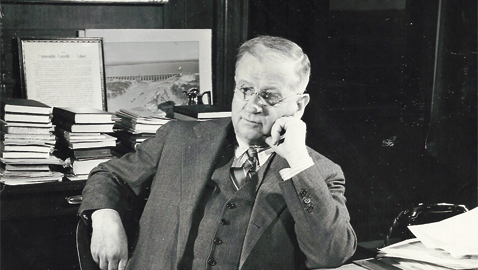

More than a few historians rate Harold LeClair Ickes as the greatest Secretary of the Interior to serve in the Cabinet of any president. Certainly, he served the longest, more than thirteen years.

Harold L. Ickes earned a reputation, one he carefully nurtured, as scrupulously honest in administering public affairs, as well as being a fighter. Ickes was indeed honest, but he was also self righteous, vain, controlling and craved power.

Ickes was appointed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt to serve as Secretary of the Interior and he was not FDR’s first, or even second choice for the post. Ickes had never even met Roosevelt when summoned to New York to be looked over for the post. Only Ickes and Frances Perkins, the first woman to serve in a president’s Cabinet, served throughout the entire length of Franklin Roosevelt’s time in office.

Born in Pennsylvania on March 15, 1874, Ickes moved to Chicago when a teenager, sent to live with relatives following his mother’s death. Harold Ickes was quite nearly penniless and was a newspaper reporter until he earned a law degree. Ickes became a somewhat prosperous lawyer and married quite well. Ickes’ wife, Anna Wilmarth, was a wealthy woman and served several terms in the Illinois state legislature.

Anna and Harold Ickes built a spectacular home on seven acres in the Hubbard Woods area of Winnetka. Ickes could not help but supervise every detail of the house and it took four years to build and furnish. The original budget for the home had been $25,000, but by the time it was finished it cost three times as much. One of the first dinner guests when the house was opened was Theodore Roosevelt.

Ickes had left the Republican Party in 1912 to follow former president Theodore Roosevelt into the new “Progressive” or “Bull Moose Party.” Ickes eagerly accepted the assignment to manage TR’s campaign in Cook County. Theodore Roosevelt lost to Democrat Woodrow Wilson and like TR, Ickes was quick to resume his Republican affiliation and supported Charles Evans Hughes for president in 1916. In 1920, Ickes backed Hiram Johnson, senator from California as well as Theodore Roosevelt’s running mate in 1912.

Harold Ickes relished a good fight and engaged in plenty of them throughout his long life. Ickes was an opponent of Samuel Insull, the utilities magnate, as well as a foe of sometime Mayor William Hale Thompson. Thompson, a Republican, was Mayor of Chicago when Al Capone was at his peak. The city was riddled with corruption and Thompson was an embarrassment to many people, not the least of which was Harold Ickes. The future Secretary of the Interior also feuded with Colonel Robert “Bertie” McCormick, owner and publisher of the Chicago Daily Tribune. The McCormicks were a powerful political family in Illinois; Medill McCormick served as United States senator for a time before committing suicide after losing a reelection campaign. Medill McCormick’s wife, Ruth Hanna, was the daughter of one of the most powerful Republican bosses of all-time, U. S. Senator Mark Hanna of Ohio.

While active in Chicago, hardly anybody outside of Chicago had ever heard of Harold Ickes. Franklin Roosevelt’s first choice for Secretary of the Interior was Hiram Johnson, who turned him down. FDR’s second choice was yet another progressive Republican senator, Bronson Cutting of New Mexico. Cutting also refused the post, preferring to remain in the Senate. It was Senator Hiram Johnson who first suggested the name of Harold Ickes to Franklin Roosevelt.

Ickes had bolted the Republican Party in 1928 to support Democrat Al Smith for president; he supported Franklin Roosevelt in 1932 and helped to organize other progressive Republicans on FDR’s behalf. Still, Ickes was almost unknown to Franklin Roosevelt.

Unlike Johnson and Cutting, Harold Ickes very much wanted to be Secretary of the Interior. Roosevelt almost casually offered Ickes the Interior Department, an offer Ickes accepted with alacrity.

Honest, plain spoken, almost fearless, frequently petulant and all too ready to bask in the radiance of Franklin Roosevelt’s sunny personality, Harold Ickes took over a department that had been if not much maligned, at the very least suspect. Ickes worked extraordinarily long hours and it soon became apparent his marriage was not a happy one. An inveterate diarist who committed virtually every detail of his life to the written page, Ickes was apparently engaged in an affair with a younger woman.

During the first days of the New Deal, Harold Ickes set to cleaning up the Interior Department with a will. Ickes cleaned out the Bureau of Indian Affairs, which had largely been administered by incompetents and had been honeycombed with corruption. Ickes had a genuine concern for the welfare of American Indians and completely reshaped and revitalized the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Ickes also proved to be highly acquisitive, greatly expanding the National Parks. Under Ickes as Secretary of the Interior were the national parks, the Bureau of Indian Affairs, the country’s natural resources, as well as the territories of Puerto Rico, Hawaii, and Alaska. That responsibility would have been more than enough for most men, but not Harold Ickes.

When President Franklin Roosevelt decided to begin a massive works program, he created the Public Works Administration and named Harold L. Ickes as the administrator. Unlike the Works Progress Administration run by social worker and presidential intimate Harry Hopkins, Ickes was scrupulous in expending billions of dollars. During a six-year period, Ickes oversaw the construction of quite nearly 20,000 projects. Those projects ranged from building hospitals, bridges, the Key West Highway, the Lincoln Tunnel in New York, and completing the Hoover Dam in Nevada. It was Ickes, who had no love for former president Herbert Hoover, who strongly objected to the dam being named for Hoover and promptly rechristened it “Boulder Dam” at his first opportunity. Hundreds of schools and even sewer systems were built during Ickes’ reign as administration of the PWA.

For a little fat man, Harold Ickes was a whirlwind. Ickes was also one of the most effective speakers for the New Deal and could be relied upon to answer public attacks by Republicans and those opposed to the Roosevelt administration. Ickes was progressive by any standard, having been an official in the Chicago NAACP and a strong supporter of civil rights. Ickes was horrified by the wartime internment of Japanese-Americans and when the Daughters of the American Revolution closed their doors to black singer Marian Anderson, it was the Secretary of the Interior who offered the use of the Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall.

While Harold Ickes always disclaimed any interest in the presidency, it seems the presidential bee buzzed around in his own head more than a few times. In his diaries, Ickes despaired about Franklin Roosevelt’s reelection campaign in 1936 – – – a campaign FDR ultimately won handily, carrying every state in the nation save for Vermont and Maine. Ickes reproached himself for not having resigned from the Cabinet in 1935 and noted there were those who thought he could have been the Republican nominee for president in 1936. Ickes claimed he realized he could never have been nominated as he would have righteously refused to give in to party bosses, but the speculation was an utter fantasy. The GOP would never have nominated any nominal Republican who had not backed a party ticket in years or one who had served in FDR’s Cabinet.

Harold Ickes eventually got over his jitters about Roosevelt’s reelection prospects, but he continued to relish the idea he might become FDR’s designated successor in 1940.

One of his greatest moments was when Harold Ickes introduced Miss Anderson to a crowd of 75,000 people on an Easter Sunday at the Lincoln Memorial.

Speaking with a flat, somewhat nasal Midwestern voice, Ickes proclaimed, “When God gave us this wonderful outdoors and the sun, the moon, and the stars, he made no distinction of race, creed, or color.”

Ickes spoke of justice being blind and found it fitting Miss Anderson would sing at the Lincoln Memorial, celebrating the man who struck off the chains of slavery for the people of the singer’s race. It was a memorable and powerful speech.

Secretary Ickes engaged in a long running feud with fellow Cabinet member Henry A. Wallace of Iowa. Wallace was Roosevelt’s Secretary of Agriculture and Ickes had a dream of turning the Interior Department into a new Conservation Department. Ickes coveted the Forestry Service for his own Department; as it stood, Forestry was part of Wallace’s Department of Agriculture. Harold Ickes constantly cajoled, wheedled, pleaded, pouted, and generally made a pest of himself in trying to get President Roosevelt to authorize the switch, which Wallace vociferously opposed.

Ickes grumbled the forestry service had the most powerful lobbying group in the country behind it, which naturally continued to resist the Secretary’s attempt to make it part of the Interior Department.

S.B. Snow, a Regional Forester in the Forest Service thought Secretary Ickes to be “overambitious, ignorant, egocentric, ruthless, unethical and highly effective.”

Ickes was no slouch in ladling out invective himself, both publicly and privately. His estimate of Colonel Robert McCormick of the Chicago Tribune, was recorded in his diary and it is memorable.

“That great, overgrown lummox of a Colonel McCormick, mediocre in ability, less than average in brains and a damn physical coward in spite of his size, sitting in the tower of the Tribune building with his guard protecting him while he squirts sewage at men whom he happens to dislike.”

Ickes also dropped off another bon mot that became famous about Louisiana’s “Kingfish”, Huey Long.

“The trouble with Senator Long,” Ickes observed, “is that he is suffering from halitosis of the intellect. That’s presuming Senator Long has an intellect.”

Harold Ickes’ heart soared each time he left the White House believing Franklin Roosevelt had agreed to give him forestry. Similarly, Ickes’ heart sank to the depths of depression and despair when he discovered things were oftentimes not what he perceived them to be and perhaps FDR wasn’t quite as committed to making the change.

Still, Ickes plotted and planned, constantly thinking of possible exchanges of responsibilities and services between the two departments. Ickes wanted to be teacher’s pet and he was almost giddy like a schoolgirl when he felt President Roosevelt was bestowing his especial favor upon the Secretary. Conversely, Ickes was bitterly jealous of rivals inside the Cabinet or others who seemed to be Roosevelt favorites. Ickes records his distaste for the sole woman in Roosevelt‘s Cabinet, Frances Perkins, who invariably tried to catch the president on the way out of Cabinet meetings to talk, at least to Ickes’ mind, endlessly. Yet, Ickes always seemed to have some matter or point he wished to discuss with Roosevelt after each Cabinet meeting.

When especially peeved or pouting, Harold Ickes would pen a letter of resignation, which Roosevelt always declined. FDR would use his charm, which certainly had its effect with Ickes. It was a rare occasion when Ickes was not resigning or seriously considering resigning. For one who truly relished a fight, Ickes’ own skin was paper-thin.

Ickes was horrified by what he observed in Europe before the outbreak of World War II. Ickes bluntly denounced the “raids of the nightshirt nations.” Ickes told an audience in 1937 those same nations “constitute the greatest threat to civilization since the democratic principle became established.” That same year, Ickes noted the suffering of Jews in Europe, well before most Americans paid the slightest attention to such things, and he denounced the “bitter hate” that had been “fanned into a searing flame.”

“It seems that the false god of racism must have its devil upon which it can pour out it objurgations, wreak its blood vengeance,” Ickes concluded.

Despite his flaws, Franklin Roosevelt seemed to value Harold Ickes as a true liberal, as well as spokesman for the administration. It was Ickes who frequently made replies to attacks upon the administration, or launched lightning bolts into the midst of the administration’s critics and enemies.

Harold L. Ickes was not only able, but he was also useful.