By Ray Hill

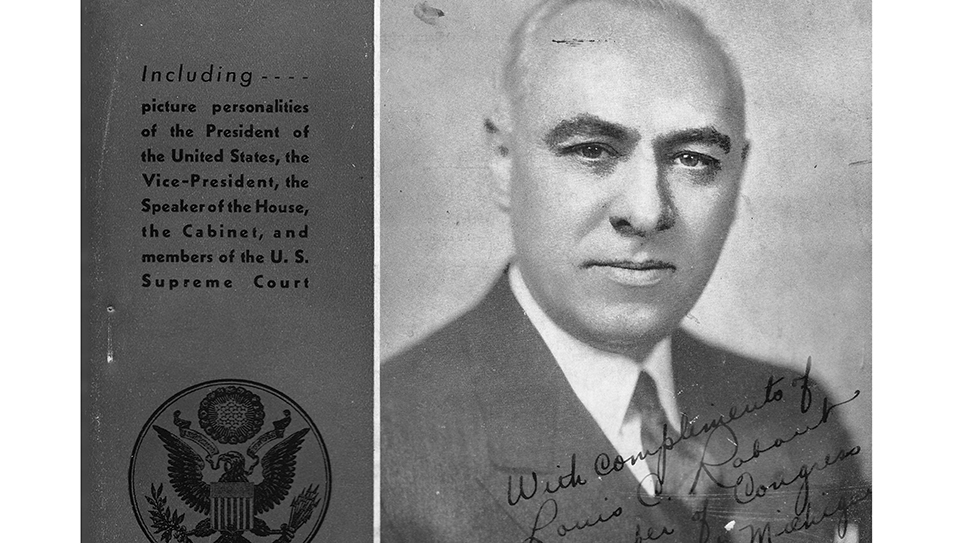

Joseph W. Martin Jr. is probably a name unfamiliar to most folks today as he has slipped into the pages of political history, yet for decades he was a national figure of great significance, especially inside the Republican Party. Joe Martin served in Congress for an astonishing forty-two years and was twice Speaker of the House. Between 1931 – 1995, a period of sixty-four years, only one Republican was elected Speaker and that was Joe Martin. The Massachusetts congressman served two different, non-consecutive stints as Speaker of the House, from 1947 – 1949 and again from 1953 – 1955. Martin was Chairman of the Republican National Committee during the 1940 presidential campaign of dark horse candidate Wendell Willkie.

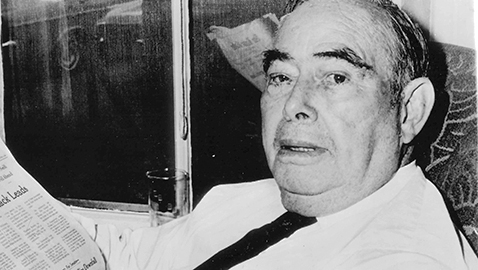

Personally, Joe Martin was a highly likeable fellow, well respected by those he served with, including Democrats. Martin’s counterpart while he served as GOP leader in the U. S. House of Representatives was Democrat Sam Rayburn. The Texan and the little man from Massachusetts were warm personal friends, even though they disagreed on most political issues. Described as a “compassionate conservative” by his biographer James J. Kenneally, Martin was not a physically imposing man; quite the contrary. Diminutive and frequently appearing rumpled and disheveled. Joe Martin was one of the leading opponents of Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal, although the congressman never forgot the working man and voted for the minimum wage. As a youngster, Joe Martin was a good enough softball player to become a semi-professional. Living in North Attleboro, Massachusetts, Joe Martin worked for the Evening Chronicle as a delivery boy and later became the managing editor. Eventually, Martin become the publisher of the Evening Chronicle and during his long career election night parties were always held in the newspaper’s offices. Many decades later when Joe Martin dictated his autobiography, he recalled the North Attleboro of his youth as a wonderful place to grow up and remembered he had made many friends as a newspaper delivery boy. Martin thought folks at that time were willing to help a young man and observed, “No one bothers anymore. People are colder and more indifferent than they used to be.” While Joe Martin was a bright young fellow, he felt he needed to help his parents put his younger brothers through school. While serving in the Massachusetts State Senate, Joe Martin used most of his $750 salary to pay for his brother Edward’s college expenses. After serving in both houses of the Massachusetts state legislature, Joe Martin was first elected to Congress in 1924. Rising to become Speaker of the House, Joe Martin had been in the presiding officer’s chair when Puerto Rican nationalists opened fire on the House while it was in session, wounding several congressmen.

Martin loyally supported the program of President Dwight D. Eisenhower throughout the 1950s but in 1959, following a devastating defeat for the GOP in the midterm elections, Joe Martin was ousted as the Republican Leader of the House. Martin was bitter his loss came at the hands of Charles Halleck, his deputy as Leader, who was more conservative. Halleck prevailed by a 74 – 70 vote.

Joe Martin also was open about the failure of President Eisenhower to help him in his moment of political need. To the surprise of many, Joe Martin started all over again as a backbencher, save for his seniority. Providing excellent constituent service, Martin was routinely reelected every two years, even after Massachusetts transitioned from a reliably Republican state to a more Democratic one.

On February 20, 1966, Congressman Joe Martin announced he would seek a 22nd term in the House of Representatives. “I’m like an old race horse,” Martin declared. “I am ready for the next race,” the eighty-one year-old congressman told a Boston Globe reporter. “I think my district is in pretty good shape, and I’m not doing too much worrying.” Joe Martin confessed he had pondered retirement, but decided against it, saying, “But just recently I went to see the doctor, and he said I’m in fine shape.” Martin indicated so long as he was healthy, he would continue to run for Congress.

Yet Martin should have been worried. The congressman faced a serious opponent in the primary, Margaret “Peggy” Heckler, a mother of three and housewife who had been elected to the Massachusetts Executive Counsel. Also known as the Governor’s Council, Council members approved or disapproved of executive decisions such as gubernatorial appointments, pardons and commutation of sentences and the like. Running on the catchy slogan, “Put a Heckler in Congress,” the redheaded Peggy Heckler was a formidable candidate, having been the first woman elected to the Massachusetts executive Council. Heckler had been the only woman in her law class and held a law degree.

The Globe published a report speculating the political class was wondering if Joe Martin really meant it when he said he would run for reelection. The “Political Circuit” column stated there were at least three anxious candidates waiting in the wings to run if Martin eventually bowed out of the race. The Political Circuit column also revealed Peggy Heckler had already told friends she intended to run even if Congressman Martin stayed in the race. In late June, Margaret Heckler made it official; she was running against Joe Martin inside the Republican primary. It was no secret Martin had been physically ailing for sometime, and his absences from the House were increasing and for longer periods of time. In her announcement statement, Peggy Heckler said the problems facing Massachusetts and the country “cannot be handled except by attentive, full-time representation.” Heckler’s announcement came despite popular GOP Governor John A. Volpe having endorsed Martin. The governor had told reporters Congressman Martin was “a pretty able man and as long as he feels he can do the job I’m going to abide by his wishes.” Volpe made his announcement at almost the same time Heckler was rolling out her declaration of candidacy. The governor denied he was attempting to “upstage” Mrs. Heckler, who confessed she had been “extremely shocked” by Volpe’s support for Martin. Throughout her statement, Heckler hammered home the need for “full-time” representation of the district. When Mrs. Heckler had stressed “energetic, full-time representation”, a reporter quickly asked if she felt Joe Martin lacked those particular qualities as a congressman. Margaret Heckler deflected the question, saying she intended to run a “positive campaign” for Congress. Mrs. Heckler said she was not running against Martin, but rather campaigning upon her own record and capabilities. As Gloria Negri wrote in the Boston Globe, Margaret Heckler had “put on her kid gloves to challenge Joe Martin for his congressional seat…”

Heckler did say she was running because many Republicans in the district were “concerned” and while she felt “deep respect for our present congressman” that attitude “should not and must not silence us from acknowledging the needs of today.”

Times had indeed changed considerably since 1925 when Joe Martin had first been elected to Congress. When Joe Martin began his congressional service in 1925, the country was booming with the prosperity of the 1920s, which burst with the stock market crash in 1929 and the onset of the Great Depression, which brought unprecedented suffering and misery to many Americans. Joe Martin served through the greatest conflict the world has ever known, the Second World War, as well as the Korean War. Martin led the Republicans in the House of Representatives during the Eisenhower administration and served through John F. Kennedy’s tragically abbreviated New Frontier. A bachelor who had little life outside the Congress, Joe Martin’s entire life had become his job. William “Fishbait” Miller in his memoirs noted unlike many of his colleagues, Joe Martin didn’t smoke, drink alcohol or chase women; in fact Fishbait remembered, Martin “didn’t do anything.”

As the two candidates attended a parade in Needham, the Globe reported if the applause for Heckler and Martin was any indication, the “comely councilor” was going to give the congressman a run for his money in the Republican primary. Heckler, from Wellesley, received an enthusiastic reception while Congressman Martin got only “polite applause.”

There was some irony in the race between Joe Martin and Peggy Heckler. When Martin had first run for Congress, he ran against an eighty-three year-old incumbent, William S. Greene, in 1924. The young candidate had lost the primary, but when the elderly Greene died later that month, Martin was named as the GOP candidate for the general election and had served continuously ever since. Naturally, Peggy Heckler quoted from Joe Martin’s own congressional campaign against an aging and ailing incumbent. As quoted by the Heckler campaign, Joe Martin had urged, “This is not the time for sentiment but the time to put on guard the men best capable of rendering efficient service. Too much is at stake otherwise.

“The office of congressman is a position for one in vigorous health if the people are to be adequately served. President Coolidge will be reelected and he needs my help,” Martin had told voters in 1924. “If the country needed vigorous service in those years,” Margaret Heckler wryly observed, “certainly the size and complexity of our nation and government today demands even greater vigor.”

To rebut the assertion the congressman’s health and energy had seriously declined, it was not Joe Martin who sought to allay those concerns, but rather his Administrative Assistant, Ernest Ladeira. “Of course he’s in Washington during the week, but he gets out to meet the people on the streets of the district on weekends.” The congressman had attended a clambake, a campaign ritual akin to fish fries and barbecues in the Southern regions for the Northeast, in Norton. According to Ladeira, Joe Martin would be out shaking hands in a couple of towns in the district that weekend. “His campaign schedule naturally depends on when the business of Congress allows him to get home,” Ernest Ladeira reminded a reporter. Local Democrats sensed the possibility of an upset, as the area had become increasingly Democratic even though Joe Martin continued to win reelection to Congress. Since 1958, even in ordinarily terrible years for Republicans, Joe Martin would win better than 60% of the vote in his congressional district. Edward F. Doolan had run against Martin seven times and was running in the Democratic primary once again in 1966. Doolan had never come close to beating Martin. Patrick H. Harrington Jr. of Somerset had been elected to the local county commission three times and believed if Martin happened to lose the GOP primary, the district would elect a qualified Democrat. Harrington insisted the district was inherently Democratic but Congressman Martin’s constituent service was so good “he gets the votes of Democrats on the basis of personal favors he has done for them over a period of 40 years in Congress.”

In the end, Joe Martin could not overcome the primary reason for the defeat of many longtime incumbents: the hand of time, which slows down for no man.

On Election Day, his legs crippled by painful arthritis, Joe Martin got up early the next morning, walking slowly, carefully, to go and vote. That night, Congressman Joe Martin went to bed at 8:00 p.m. The congressman lived in his home with his widowed sister Nettie Kelley who told reporters, “It is better to get important news – – – good or bad news – – – in the morning. Then you can handle it a little better.” Joe Martin walked upstairs to the second floor bedroom he had slept in forty-two years earlier when he had first been elected to Congress. As he watched the television news, the congressman told a visiting reporter, “I’ve always done the best I know how. If the people want me, fine. If they don’t I ain’t going to get upset.”

The vivacious Peggy Heckler won almost 56% of the vote in the Republican primary over the old and ailing Joe Martin.

Like most of the people he represented, Joe Martin was a good and decent man. Throughout his lifetime and career, he always did the best he knew how.