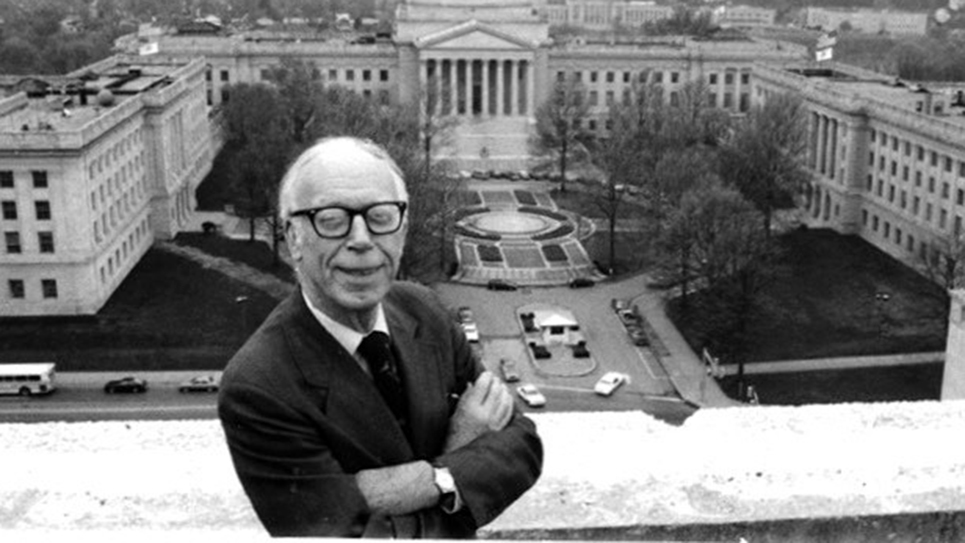

It is truly rare for a politician to be a fixture of the politics of his or her community, state or nation. It does happen, but those political figures whose influence and or service span generations are rare. Ken Hechler was one of those scarce individuals. It is all the more remarkable because Hechler was not a likely political figure to begin with; Ken Hechler did not radiate charisma, quite the contrary. Hechler was not a spellbinding orator, nor an especially attractive and compelling figure. Indeed, Ken Hechler was balding, bespectacled, bookish, and seemed exactly like what he was: a professor. Yet, Ken Hechler was anything but ordinary. Hechler’s long political career was filled with seemingly inexplicable decisions and quixotic campaigns for public office, several of which were spectacular failures. Yet there was an immovable feature of every campaign waged by Ken Hechler, which was also a trait of the candidate’s personality: complete sincerity.

Ken Hechler’s agenda in Congress seemed contrary to much of what one would have expected from a representative from West Virginia. Once in the House, Hechler championed regulations on strip mining and civil rights. Congressman Hechler also fought hard for coal mine safety and compensation for those suffering from black lung disease. Ken Hechler was one of the few congressmen who marched with Dr. Martin Luther King in Selma, Alabama.

Before World War II, Hechler had been a member of the faculties of Princeton and Columbia Universities, as well as Barnard College. During the Second World War, Ken Hechler was drafted into the Army where he graduated from the Armored Force Officer candidate school. Assigned to the European Theater of the war, Hechler was designated as a combat historian, a role which came naturally to him. As the armed forces of the United States landed at Normandy Beach and swarmed through France, fought the bloody Battle of the Bulge, and liberated France, Ken Hechler documented American progress and fighting men. Out of Ken Hechler’s notes came a bestselling book, “The Bridge at Remagen,” which was also turned into a movie by Hollywood. Another interesting sidelight to Ken Hechler’s military career was the fact he was assigned to interview several of the top Nazis prior to the opening of the Nuremberg Trials. One of those Hechler interviewed was the top Nazi in Allied custody, Hermann Goring, the Reich Marshall of Hitler’s Germany and the head of the once-feared Luftwaffe.

In addition to Goring, Hechler interviewed Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel and General Alfred Jodl, as well as Nazi Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop, all of whom were found guilty of war crimes and subsequently executed by hanging. Hechler liked to recall Goring’s boast that he could lead the German armies alongside the Allies and “knock hell out of the Russians.”

It had been writing that had sent Hechler’s career in the Army in a different direction from what he had originally intended. Hechler told an interviewer for the Harry Truman Presidential Library an officer caught him writing an autobiography “after lights’ out.”

“I was using a flashlight under my blanket in bed,” Hechler told the interviewer. “He said, ‘This is the most remarkable autobiography. I don’t think you ought to be a tank commander. I think we ought to assign you to something a little bit more useful in the Army.”

Upon returning to the United States following the war, Hechler ended up in one of the most unlikely places for any former soldier who wasn’t Dwight D. Eisenhower: the White House. After briefly having returned to teaching at Princeton, Hechler became a special assistant to President Harry Truman from 1949 – 1953. Hechler served as a special research assistant for Democratic presidential nominee Adlai Stevenson in the 1956 campaign.

Among Ken Hechler’s duties in the Truman White House was helping with speeches for the President. Hechler was especially helpful in tailoring remarks for Truman’s famous 1948 reelection campaign whistle-stop tour by train.

Following a stint as director of the American Political Science Association in Washington, D. C., Hechler was named to the faculty of West Virginia’s Marshall University in 1957. A year later, Professor Hechler announced he was running for Congress. Hechler dispatched two candidates in the Democratic primary, winning the nomination of his party with a plurality of the vote.

West Virginia’s Fourth Congressional District included the City of Huntington and several towns where organized labor was strong, yet the incumbent was a Republican. Dr. Will E. Neal was no ordinary Republican. Neal had been the oldest man ever to be elected as a freshman legislator when he first defeated Congressman M. G. “Burnie” Burnside (who had also been a college professor) in 1952. Burnside made a comeback in the 1954 election, only narrowly eking out a 500-vote victory over Will Neal. Former congressman Neal ran again in 1956 at eighty-one and beat Burnside by more than 8,000 votes.

Even at eighty-three years of age, Congressman Neal proved to be a formidable candidate, but 1958 was a terrible year for GOP candidates across the country because of an economic recession. The recession was especially brutal in West Virginia and Ken Hechler won the general election with just over 51% of the vote.

The biggest electoral test of Hechler’s hold on his constituency came following redistricting in 1972. During the decade of the 1950s West Virginia boasted six seats in the U.S. House of Representatives. As the state’s population continued to decline, by 1970 the state was down to four House seats. James Kee, who had followed both his father and mother into the House of Representatives, was considered to be the heavy favorite in the 1972 Democratic primary. A Kee had represented West Virginia’s Fifth Congressional District since 1933; the family held on for forty years. Although he had been in Congress for eighteen years, Ken Hechler still remained a political outsider to the good ol’ boy network in his adopted state. While it remained designated as West Virginia’s Fourth District, it was mostly composed of the remnants of James Kee’s old Fifth District.

Two other candidates entered the Democratic primary for Congress that year including the two incumbent congressmen. Yet Hechler astonished virtually everyone when he emerged the winner. Hechler won 52% while Jim Kee polled only 25% of the ballots cast. The remainder was divided between the two other candidates.

Ken Hechler won the general election handily in 1972 and was unopposed in 1974. In 1976, Congressman Ken Hechler voluntarily gave up his seat in the House of Representatives to become a candidate for the Democratic nomination for governor. It was a crowded primary with two former gubernatorial nominees running again, former Secretary of State John D. “Jay” Rockefeller IV and James Sprouse. Both Sprouse and Rockefeller had lost general elections to Republican Arch Moore, in 1968 and 1972 respectively. Moore was barred from seeking a third term in 1976 and Democrats felt certain the statehouse would once again be held by a Democrat. Rockefeller’s bid was fueled by his free spending from his large personal fortune. Hechler, who was not a prodigious fundraiser, ran a very poor third, winning less than 13% of the votes cast.

Realizing the enormity of his political mistake, Hechler quickly announced he would wage a write-in campaign for his seat in the House against the regular Democratic nominee, Nick Joe Rahall. Rahall had been an aide to the most popular officeholder in West Virginia, Senator Robert Byrd. Rahall also came from a prominent and wealthy family and once again money made a difference. It is a tribute to Hechler’s personal popularity that he carried two counties running as a write-in candidate. Rahall won 45% of the vote, followed by Hechler with quite nearly 37%. The GOP candidate ran third in the general election.

In 1978, Hechler resolved to try and win back his seat in Congress and filed to run inside the Democratic primary, believing he could upset the young incumbent by being on the ballot. Hechler ran a strong race, polling quite nearly 44% of the vote inside the primary, but he lost to Nick Joe Rahall.

After his unsuccessful campaigns, Hechler returned to teaching at Marshall University and also taught at West Virginia State University and the University of Charleston. Yet Hechler was not finished with politics. In 1984, Hechler filed to run for statewide office once again. This time, Hechler aimed for the Secretary of State’s office and in a field of six Democrats competing for the nomination, the former congressman won easily, garnering 54% of the vote.

West Virginia was beginning to see some political changes which were becoming more apparent in the 1984 election. President Ronald Reagan won the Mountain State that year and former governor Arch Moore was retaking the statehouse. Even Jay Rockefeller quite nearly lost his race to succeed U. S. Senator Jennings Randolph. At the same time, Ken Hechler was winning the Secretary of State’s office with almost 64% of the vote. In his later years, Hechler was a familiar sight in his bright red Jeep, going from meeting to meeting.

As West Virginia’s Secretary of State, Hechler remained a foe of political corruption. The Secretary of State is also the chief election officer and it was Hechler’s office that uncovered evidence that Sheriff Johnnie Owens of Mingo County was selling influence for $100,000. Owens was convicted in 1988.

The seventy-four-year-old Hechler was reelected without opposition in either the primary of general elections in 1988. Two years later, Hechler yet again entered the primary in another attempt to take back his old seat in the House of Representatives from Nick Joe Rahall. The incumbent won the primary contest handily.

Undeterred, Hechler ran for reelection as Secretary of State in 1992, winning the primary easily and the general election with quite nearly 70% of the vote. At age eighty-two, Ken Hechler repeated the feat in the 1996 general election.

Evidently, Ken Hechler never gave up his desire to return to Congress. The eighty-four-year-old Secretary of State entered the Democratic primary for West Virginia’s Second Congressional District and ran third, well behind the eventual winner. Four years later, Hechler made history when he won the Democratic nomination for Secretary of State at age ninety in a field of seven candidates. Still, the former congressman only scraped by runner-up Natalie Tennant by 1,118 votes.

Ken Hechler lost the 2004 general election narrowly to Republican Betty Ireland. Hechler’s last political hurrah came at age ninety-six when he ran for the Democratic nomination for the United States Senate in the special election to fill the vacancy left by the death of Senator Robert Byrd. The nomination was won by then-Governor Joe Manchin. Hechler had no illusions he could win the primary, but ran so that those folks opposed to mining by mountaintop removal would have a candidate to support.

A bachelor for virtually all his life, Hechler finally married his longtime companion Carol shortly before he died at age 102. When Hechler died, then-Governor Earl Ray Tomblin referred to the late congressman as “a true West Virginia treasure.” Former opponent Senator Joe Manchin paid his own tribute to the old political warrior.

“Ken was a man of his word – – – a fierce advocate for West Virginians who was always willing to help any person in need,” Manchin said.

I had my own conversation with Ken Hechler after he was out of office to interview him for a biography of Tennessee’s Senator Kenneth McKellar. The former congressman was bright and alert and his memory seemed remarkably sharp. Hechler was kind, helpful and interested. All of those adjectives make for one very fine public servant. Ken Hechler exemplified service to others and lived his life accordingly and was a truly extraordinary person.

Every so often, some person comes along and when that person’s life is over, others marvel he or she was “one of a kind.” Ken Hechler really was one of a kind.