The Senator From Arkansas

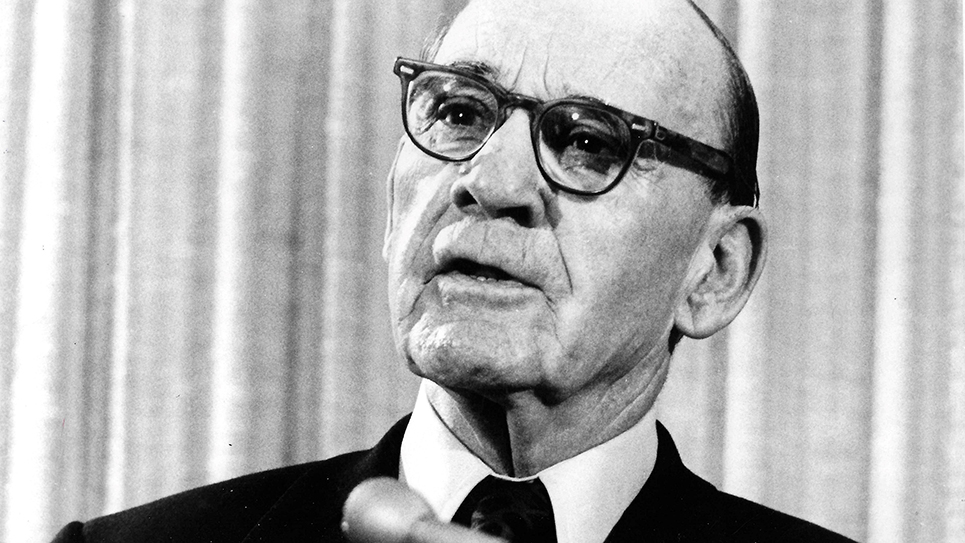

John L. McClellan

By Ray Hill

John Little McClellan remains the longest serving United States senator from Arkansas. Not one to waste words, John L. McClellan had the appearance of a fierce church elder merely waiting to spot the first flicker of frivolity. When McClellan came to national prominence for his fearless investigations into organized crime, the senator was featured in a profile by TIME magazine, appropriately titled, “Man Behind the Frown.”

I recall meeting Senator John L. McClellan in Washington, D.C., in 1977. It was towards the end of his life and he was waiting for the Senate subway, a small car that ferried senators, staff and tourists back and forth between the Capitol and the Senate Office buildings. McClellan was wearing a brown suit, a wide matching tie, and leaning on a cane. I knew who he was and approached him, calling out, “Hello, Senator McClellan.” The senator stuck out his hand and smiled, pleased to be recognized. “You from Arkansas?” he asked. “No, sir,” I replied, “I’m from Tennessee.” “Next best thing,” McClellan said. I’ve never forgotten that exchange.

McClellan was a man who rose to the heights of political power, but he also knew suffering. Throughout his life, John L. McClellan’s faith was tested regularly. Death stalked those McClellan loved throughout his long life. John L. McClellan was named for Congressman John Little. When the congressman heard about his namesake, he sent the little fellow $5.00 (quite nearly $200 today). McClellan’s mother, Belle, “a lovely woman with a fine singing voice,” died six weeks after the birth of her child. As she lay dying, Belle McClellan asked for only one thing: out of the $5 sent by Congressman Little, a part of that money be used to buy her son a Bible.

John’s father Isaac was a man of many talents, working as a schoolteacher, farmer, editor of a country newspaper, and lawyer. Isaac remarried three years after Belle’s death and began tutoring his son when John was only four. “Ike” McClellan also liked politics and his frequent companion on the campaign trail was his young son. McClellan’s favorite was Jeff Davis, a talented demagogue who was usually attired in a light gray Prince Albert coat and could orate on just about any topic at any time. Davis was a man who attracted devout supporters and equally determined political enemies. Young John McClellan took things to heart and even as a child, he had a serious demeanor about him. Ike McClellan later said, “I should have held off until John was a little older and could understand that our opponents didn’t really mean what they said.”

While running the family farm, young John studied law books, causing one family friend to say, “His father was a lawyer – – – and his only mother was the law.” Evidently John L. McClellan was a prodigy. Ike McClellan had to wrangle special permission from the Arkansas state legislature to permit his son to take the oral test required of aspiring attorneys at the age of 17. John McClellan scored a 90 on his examination, well above the minimum requires for passage. It surprised nobody who knew him that John L. McClellan had become the youngest attorney in Arkansas.

The same year John McClellan passed the bar examination, he married Eula Hicks, reputedly the prettiest girl in Sheridan. While John went away to fight in the First World War something happened. Whatever it was, only John McClellan knew, and he remained utterly silent about their 1921 divorce.

McClellan worked hard and by age 30 was elected prosecuting attorney for a judicial district comprised of three counties. McClellan’s knowledge of the law was complete, and his cases were well-organized and thorough, although his father Ike was a defense attorney and understood emotions, people and juries. As prosecuting attorney, McClellan’s integrity was never challenged. John McClellan “feared nothing and favored no one.” He prosecuted one boyhood friend for moonshining. The offender was convicted of the crime and summarily fined. After the fellow paid the fine, he approached McClellan with steely eyes and said, “John, this time’s all right. But don’t you ever prosecute me again.” McClellan returned the glare and looked his friend square in the eyes. “Albert, I don’t care how much whisky you make or sell – – – but don’t get caught. If you do, I’m going to send you to the penitentiary.”

Representing those three counties gave McClellan a political base to challenge Congressman David D. Glover in the 1934 Democratic primary. McClellan won that race and was reelected in 1936. Almost immediately John L. McClellan showed his prickly independence. One of the Democratic “whips,” the official vote counters for the House leadership, sidled up to the newly elected congressman from Arkansas and gave a terse order to vote for a pending bill. “Look,” McClellan snapped, “you don’t know me and I don’t know you, but we’re going to get to know each other pretty darn quick. I vote as I please.” It never bothered McClellan to vote against the Roosevelt Administration and the New Deal program.

McClellan had remarried to a woman named Lucille Smith and the couple had three children together, two boys and a girl. While McClellan was serving in the House, Lucille was driving the children back to Arkansas when she became seriously ill. Stopping at the home of family in Jackson, Tennessee, she died a few days later of spinal meningitis. The marriage had been a happy one and McClellan was devastated. He thought of resigning his seat in the House of Representatives, but Ike McClellan talked his son out of quitting Congress.

John McClellan, always dedicated to his work, immersed himself in his work to the exclusion of most everything else. One worried fellow congressman urged McClellan to come with him to visit the house of friends who were entertaining a “very attractive lady.” McClellan was immediately struck by the visitor, who came down the stairs, a vision in blue hat and dress. The woman in blue was Norma Cheatham, who soon became Mrs. John McClellan. They remained married for the rest of the senator’s life.

Death visited McClellan again, striking his son Max from his marriage to his first wife, who was in North Africa as a corporal during the Second World War. Max McClellan complained of his back hurting and his superiors refused to take his complaint seriously, thinking he was “goldbricking.” Neglected by the Army’s doctors, Max McClellan died of spinal meningitis. The boy’s mother had died hating his father and her last advice to Doris and Max McClellan was to have nothing to do with the McClellan family. Yet Senator McClellan was tortured by his lack of a real relationship with his son. McClellan also carried some guilt with him for the rest of his life. Max McClellan’s body was returned to the United States almost six years after his death. Two nights before the funeral for Max, John McClellan Jr. was injured in a car accident near Fayetteville, Arkansas. Initially, the boy was not thought to be seriously injured. Senator McClellan and his family attended the funeral for Max and flew to Fayetteville. Jimmy McClellan remembered a small group awaiting the senator. “When we arrived at the airport, there was a little delegation waiting to see us. Dad looked out of the window at their faces and he knew.” Johnny McClellan had suffered from an unknown brain injury and had died that morning. Max McClellan had been buried on a Friday and the following Monday, John McClellan Jr. was laid to rest beside his mother. Jimmy McClellan would die in a plane crash in 1958.

No one could have been surprised that Senator McClellan sought solace in a bottle of bourbon. For a while his drinking increased, which caused serious marital problems and Norma demanded that he stop. “I am going to show you that I am the master of my own soul,” McClellan replied. Through sheer will power, McClellan stopped drinking and the couple remained married.

McClellan had his eyes fixed on the United States Senate and entered the 1938 senatorial primary to face the first woman ever elected to the United States Senate, Hattie Caraway. Mrs. Caraway had confounded the politicians and upset the political order when she decided to become a candidate after having been appointed to the Senate to succeed her dead husband. Caraway sat near Senator Huey Long on the floor of the Senate Chamber and Long felt sorry for the hopeless situation in which the widow found herself. Long invaded Arkansas and brought all the trappings with him, staff, literature by the ton, a sound truck, and his ability to entertain audiences. Huey and Hattie waged a whirlwind campaign and beat all her opponents easily.

Huey Long lay in his grave, felled by an assassin’s bullet. McClellan thought he could beat Senator Caraway and he almost did, falling 10,000 votes short. The congressman accused Senator Caraway of having “improper” control of federal employees in Arkansas and was critical of her record in the Senate. No speaker, Hattie Caraway used her numerous contacts and the debts owed to her from those who had benefitted from her service to Arkansas. Senator Caraway had yet another advantage, which was the support of the White House. In the end, the women of Arkansas had rallied behind Mrs. Caraway and provided her margin of victory. McClellan also insisted the 50,000 Works Progress Administration workers in the state voted for Hattie.

It was the first and only loss of John L. McClellan’s long political career. McClellan went back home to Arkansas where he opened a law practice in Camden. When Senator John Elvis Miller was appointed to a federal judgeship, he resigned his Senate seat and the governor appointed G. Lloyd Spencer, who did not seek election in 1942. Having gained statewide name recognition from his race against Senator Caraway, John L. McClellan announced his own candidacy. The Democratic primary, tantamount to election, was a crowded affair with four serious candidates. Aside from McClellan, Jack Holt, the popular state attorney general was running hard, along with two sitting congressman, Clyde Ellis and David Terry. Holt led in the first primary, only barely ahead of McClellan by 456 votes. Jack Holt and John McClellan faced one another in the run-off election, which the former congressman won by more than 50,000 ballots.

McClellan quickly established himself inside the Senate as a work horse, as opposed to a show horse. McClellan tended to his home state and the needs of his people. Two years after his election to the Senate, he was joined in that chamber by a freshman colleague: J. William Fulbright. Fulbright became known for his interest in foreign affairs, rising to chair the prestigious Senate Foreign Relations Committee in 1958. There was a subtle but noticeable rivalry between McClellan and Fulbright. The senior senator was more deeply entrenched inside Arkansas, but did not command the same respect, especially from the news media of the time, much of whom fawned over his junior colleague, especially after Fulbright broke with Lyndon Johnson over the Vietnam War.

John L. McClellan’s political primacy in Arkansas was challenged repeatedly. A bitter rivalry developed between McClellan and Governor Sid McMath, perhaps because the senator strongly suspected the governor wanted his seat in the Senate. That challenge came in 1954 and McClellan kept his temper and ignored his opponent throughout the primary campaign and won outright, beating McMath by better than 10% in the first primary, along with two other challengers.

Toward the end of his long career, McClellan faced a fresh, young, talented opponent in Congressman David Pryor inside the 1972 Democratic primary. McClellan had already been in the Senate for thirty years. In the first primary, McClellan was only 16,000 votes ahead of his young challenger and it appeared the 76-year-old senator might lose the run-off election to his young opponent. The old senator proved to be resourceful and campaigned hard personally. McClellan beat Pryor 52% – 48% in the run-off primary election to win another six-year term.

John McClellan did not complete that term, dying in his sleep on November 28, 1977, after having undergone surgery to implant a pacemaker. © 2024 Ray Hill