‘Do something about the terrible series standing’

By Tom Mattingly

Despite what you might have thought or heard, the early years of the Tennessee football program were not without their share of controversy.

The Vol football program was lucky to have survived the 1893 season. The team lost 56-0 to Kentucky A&M (later Kentucky State, then Kentucky), 64-0 to Wake Forest, 70-0 to Trinity College (now Duke), and 60-0 to North Carolina, all games played between Oct. 21 and Nov. 7. The latter three games were played away from Knoxville.

There were 256 points allowed in a 2-4 season. By contrast, Tennessee teams coached by Bob Neyland between 1926 and 1933 gave up 259 points, and that happened over 78 games.

When it came time for the 1894 season, only two players admitted they had been part of the 1893 squad. As a result, there were no teams in 1894 and 1895, with club teams being formed to help keep football alive on campus.

The leader of those club teams was Newport’s William B. Stokely, whose family would have a profound leadership role and influence on the campus through much of the 20th century and beyond.

“He learned his football at Wake Forest,” grandson Bill Stokely III has said. “He came back to Tennessee and was disappointed there wasn’t a team. He held things together in that gap. He always jokingly said he was named captain because he had the only football. He was proud of that and had fond memories.”

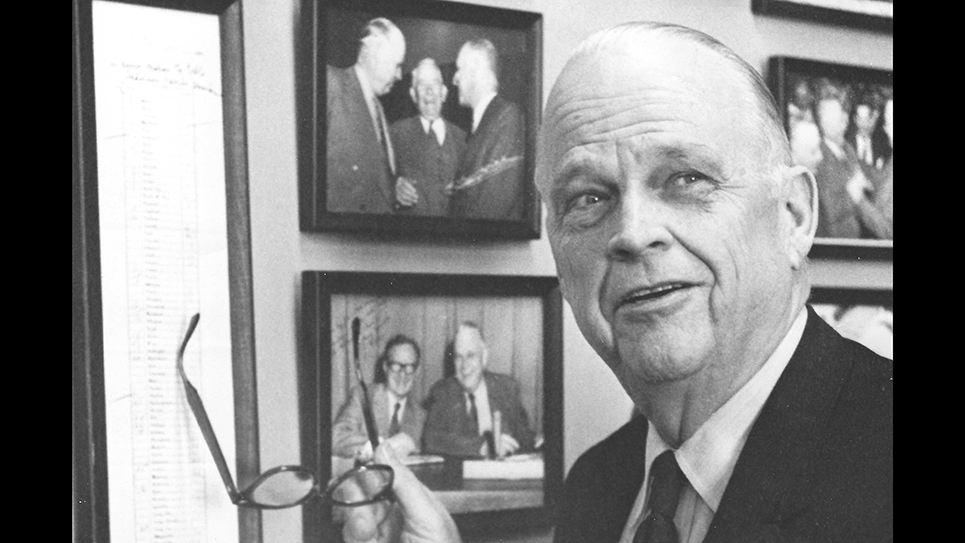

Nathan Washington Dougherty was captain of the 1909 team and spent a good part of his life involved with the Vol athletic program. His influence on campus and on the Vol athletic program resulted in the naming of the Dougherty Engineering Building on the Hill.

Dougherty also captained the track and basketball teams in 1909 and organized the hoops program that season, serving as coach and captain.

That 1909 team finished 1-6-2, not scoring a point until the Transylvania game on Nov. 21. The hype surrounding the 1909 season may have done the Vols in. Before that season, the Vols made a major commitment to be successful on the gridiron.

“I do solemnly promise upon my word as a gentleman to go into strict training from September 11, 1909, till the evening of November 25, 1909,” the pledge read. “It shall be my aim to aid or assist in any way as will help to make the University of Tennessee Football team of 1909 the best in the South.”

Upon graduating, Dougherty earned his master’s degree and taught classes at Cornell before returning to Knoxville in 1916 as an associate engineering professor.

He later became dean of the College of Engineering (1940–1956) and was chairman of the UT Athletics Board, a position he held for 40 years. Dougherty was influential in the design of Shields-Watkins Field and also helped build Tennessee football into a national program with his hiring of Neyland in 1925 as an assistant coach. The following year, Neyland was promoted to head coach, and history was made.

He was elected to the College Football Hall of Fame in 1967.

Vol football was in such straits in those days that head coach John R. Bender left U.T. to go to Knoxville High School, while M.B. Banks moved on to Knoxville’s Central High School, both apparently considering the moves a promotion.

Tennessee teams have brought Vol fans many great moments and have continued to engender great passion for the program since that time. That’s why Neyland’s name ended up on the façade of the big stadium by the river, and his game maxims are recited in the dressing room before kickoff.

Those early, often tentative years were paramount in Dougherty’s thinking the day in late 1925 he named Neyland head coach, then two months or so short of his 34th birthday.

“Even the score with Vanderbilt. Do something about the terrible series standing,” Dougherty is supposed to have told Neyland, maybe in the form of a demand. From that point on, Neyland did “something” about the series and the Vol program overall. Vol football was never the same since.

It is evident from all accounts that Neyland had a towering, dominating, and even intimidating presence. Taciturn in demeanor and seeking excellence on all fronts, Neyland’s impact was felt across the South, all across the nation.

For his part, Dougherty later called Neyland’s hiring of Captain Robert Reese Neyland the “best decision I ever made.”

Dougherty and Neyland were among the visionaries of that time.

Decatur County’s Roy (Pap) Striegel convinced Banks to outfit the Vols in their unique orange jerseys in 1922. “I get a thrill every time I see the orange and white on the football field,” he said in his later years.

As a member of the Athletics Board, he broke an impasse when the Vols were looking for a new head coach in late 1963 and seemed deadlocked about their choice.

U.T. trustee Col. William Simpson Shields provided much of the capital and land to build the first version of a stadium that would welcome crowds of more than 100,000 fans in the years to come. His contribution was estimated in the $40,000 range, equivalent to $761,426.19 today.

Visionaries come in all shapes and sizes, and their impact on those early days is still being felt more than 100 years later.