Orange and White… and Black?

By Tom Mattingly

In late October 2009, there was a great deal of interest engendered across Volunteer Nation when the Tennessee Vols were rumored to be wearing black shirts (with their orange pants) in their upcoming game against South Carolina. That was a definite break with tradition. Messing around with the traditional orange and white outfits was unheard of at that time.

That changed when the Vols ran through the “T” on Halloween night in black shirts and orange pants, thus confirming the rumors. It had to have been the worst-kept secret in Big Orange Country. For better or for worse, all kinds of uniform combinations have since been seen on Shields-Watkins Field.

Hit the rewind button to a long-ago weekend in Tennessee football. On Friday, March 31, 1939, the Knoxville News-Sentinel, perhaps breathlessly, reported that the Vols would be having an “Orange & Black Game” a day later on Shields-Watkins Field. Kickoff was slated at 2:30 p.m.

In the compiled history of Tennessee football, from the works of Tom Siler, Marvin West, Ben Byrd, Ed Harris, Russ Bebb, and many others, titled the “Tennessee Football Vault,” I have never found any reference to an “Orange & Black Game.”

The KNS also reported that the game would be broadcast on WNOX, with station manager Dirk Westegaard making the announcement. Sports Information Director Jack Joyner did the play-by-play, with local radio personality Tys Terway on the color. No mention was made of Lindsey Nelson, however.

The future broadcasting legend was a student assistant and an integral part of the Vol athletic program at the time, looking for his big break into the business of broadcasting. He literally looked for any opportunity to make an impact on the program. For Lindsey, the best was yet to come.

Unlike today, there was no effort to draw a crowd. The “World’s Largest Spring Game” promotion was 47 years away. The “Orange & Black Game” was a necessary evil, the sooner dispensed with, the better.

“Only season ticket holders, along with city officials, and a few newspaper representatives would be admitted,” read the story from March 31. A day later, on game day, another story let fans again know the rules. “Only radio sports commentators, U-T faculty, and purchasers of season tickets will be admitted,” the story read. No mention was made about the price of tickets.

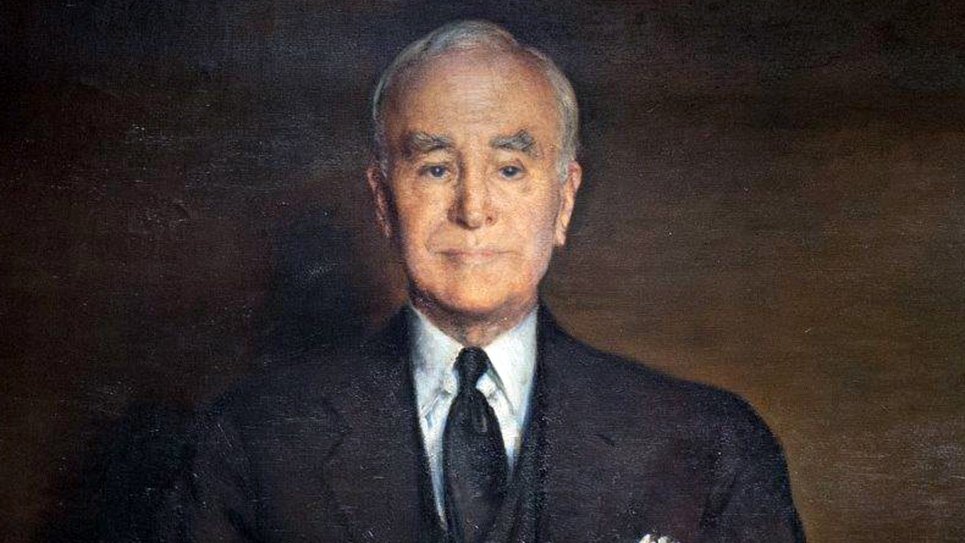

Newspaper accounts made no mention of the reasoning behind the restrictions placed on who could attend the contest. It was, as Nelson has written, a manifestation of Bob Neyland’s intense desire to have as few eyes as possible looking in on one of his practices.

“To Neyland,” Lindsey wrote in his autobiography, “a football game was too important to be threatened by the presence of outsiders.”

Neyland was suspicious about who might be watching practice, either on the practice field or at the stadium. He was so suspicious he once sent trusted aide Gus Manning to check on happenings on Cherokee Bluff across the Tennessee River. After several visits to the bluff, Gus informed Neyland that the couple he found didn’t “give a dang about your No. 10 play.”

The Orange team seemed to have the advantage in personnel, with future college football hall of fame members Bob Suffridge, Ed Molinski and George Cafego leading the way, but that seeming talent discrepancy didn’t translate to the events on the field. Bob Foxx and Bill Luttrell led the way for the Black team.

Hugh Faust was in charge of the Black team, while Bill Britton handled the Orange team. Neyland and John Barnhill were said to be “neutral observers.”

Harold Harris’s game story in Sunday’s News-Sentinel assessed the scene: “Playing their hearts out for a chance at varsity berths next fall, a makeshift machine of inexperienced reserves and untried sophomores clad in Black shirts held a more powerful Orange brigade to a 6-6 tie Saturday afternoon at Shields-Watkins Field, as the University of Tennessee spring football practice came to an end.”

Harris also reported that 1,500 fans “braved chill winds” to attend a “drab intra-squad struggle.”

Excited about an 11-0 campaign a year earlier, Tennessee fans were anxiously looking ahead to the 1939 season, one in which the Vols held 10 regular season opponents scoreless.

“The Vols are well heeled with oodles of talent for every position with the lone exception of end, where Capt. Bowden Wyatt is no longer holding sway,” wrote Harris. He might also have mentioned the loss of George Hunter at the other end, but didn’t, nor did he mention the absence of tackle Bob Woodruff.

“Considering the fact most of them are reserves or sophomores, I think the Black team did extra well to hold the so-called varsity on even terms,” said Neyland.

It has been said and written that spring games are full of sound and fury, but not really of great significance. On this day, however, seeds were sown for a historic 1939 season.

In addition, the “Orange & Black Game” is now a part of the Tennessee football literature and history.